Global protests are the result of years of neglect as deluded elite remain blind to realities

- The pandemic, war, inflation and livelihood losses have left many around the world feeling desperate

- For too long, those feelings have been overlooked by those in power, who prefer to stick to their own mandates

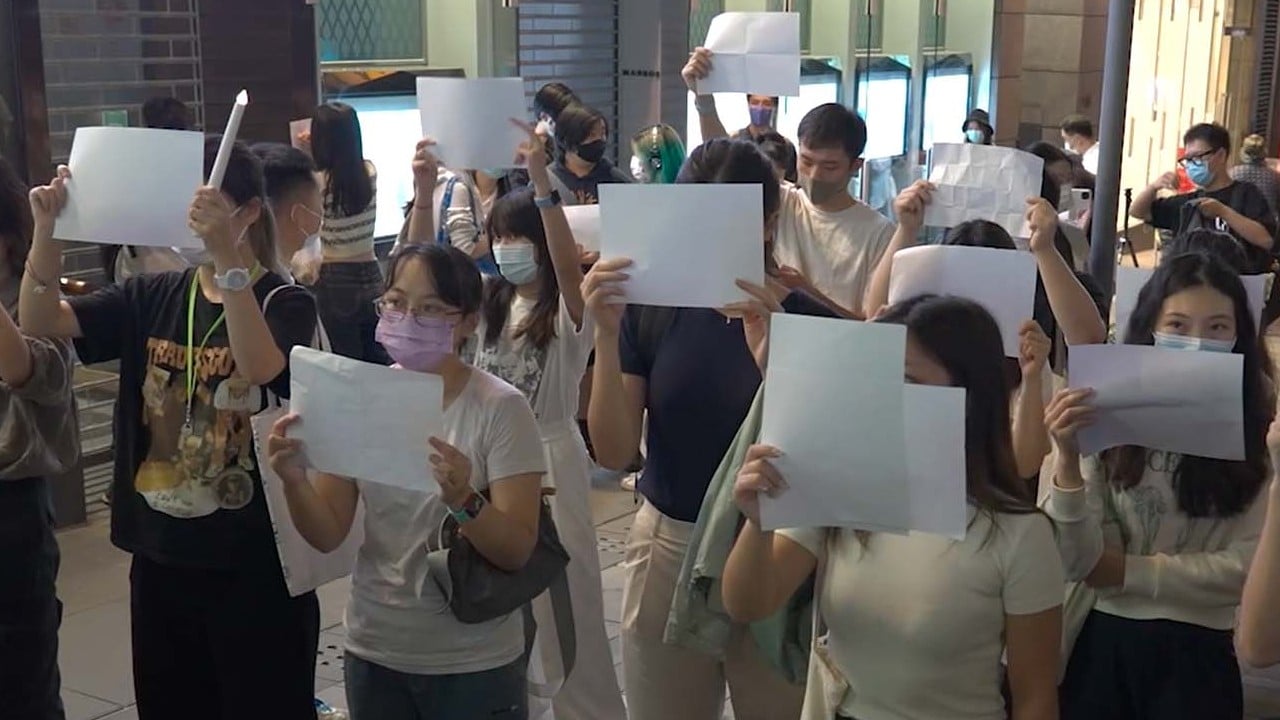

As protests erupt in China, Iran, Brazil and Europe, social scientists will have a field day dissecting why.

The economist/psychologist Daniel Kahneman asked: why are we blind to our blindness? That can be attributed to cognitive biases, which lead one party (for example, the elite or top leadership) to completely misread what the rest are feeling or thinking. This happens irrespective of whether we live in democracies or autocracies.

Princeton economist Roland Bénabou has an excellent perspective on how “groupthink” within organisations and markets leads to collective blindness. The term “groupthink” was coined by social psychologist Irving Janis in his classic 1972 study of Bay of Pigs and Vietnam war failures, in which he surmised that groups delude themselves and then deny reality in the face of facts.

The symptoms identified are: (a) an illusion of invulnerability; (b) collective rationalisation; (c) belief in inherent morality; (d) stereotyped views of out-groups; (e) direct pressure on dissenters; (f) self-censorship; (g) illusion of unanimity; and (h) self-appointed mindguards.

Does that sound familiar, given what is happening right now? Bénabou extended Janis’ work to show how wishful thinking and reality denial spread through organisations and markets. Applying the principle of “mutually assured delusion”, groups reinforce each other’s biases and either end up with market manias or market crashes.

All organisations have identified goals. They achieve them through policies, with processes and structures to implement those policies. Technocrats with PhDs who are not streetwise forget that policies have bad outcomes if the processes and structures are obsolete.

Elegant theories have a habit of failing because reality is messy and uncertain, with accidents and events that throw theories out of the window. But groupthink denies such inconvenient truths. Indignantly standing on moral principle with disregard for the real costs may result in system collapse.

The free market system is a theory, not reality, because the real world is mostly an ecosystem of different forms of government and markets, ranging from competitive markets to shades of monopolies, oligopolies or even kleptocracies.

The elite have their comfortable view of how things work, whereas the bottom half of society has to struggle with the pandemic, job losses, rising education and health costs, crime, inflation, insufficient savings, rising debt and political corruption.

Protests are often not acts of deliberation but desperation, because the protesters feel they are not in charge of their lives and those in charge do not seem to care, or worse, do not seem to be aware of the depths of their predicaments.

Clearly, the current paradigm is not working. The processes – specifically, the feedback mechanisms – are failing to tell those at the top how the bottom feels. Unfortunately, each part of government, including specialised agencies, feel they should stick to their mandates and not get out of their comfort zones.

The collective whole is not working; to blame the politicians, the civil servants or foreigners will no longer suffice. When the media itself becomes the cheerleader of one point of view rather than giving both sides of the argument, there are few forces pushing towards moderation, and everything is instead moving towards polarisation.

Drums of war drowning out calls to fight climate change and poverty

Groupthink calamities are everywhere in history. Four centuries ago, the Dutch East Indies Company arrived in the Spice Islands to kick out the Portuguese. Two centuries later, in 1810, the British fought the Dutch over control of the spice trade.

In the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1814, the spice islands were “returned” to Holland (the locals had no say in the subject), but not before nutmeg and clove seedlings were transplanted all over the British Empire, so that the Malukan spice trade lost its monopoly.

Thus, when rich countries talk about human rights, free trade and rule-based order, they should remember their own colonial history in which their groupthink was to take what they could by force, irrespective of local protests, and rewrite history in their favour.

The world would be a better place if everyone rethought how to deal with their own internal injustices and got out of their groupthink delusions.

Andrew Sheng writes on global issues from an Asian perspective