Why China’s move up value chain means Dell’s departure is no big deal

- Rather than being alarmed and making conclusions about the entire economy, the Dell news needs to be put in context of China’s development

- Labour-intensive industries are leaving the country to be replaced by higher value-added sectors, and China’s advantages are hard to replicate elsewhere

The world’s third-largest personal computer manufacturer, behind Lenovo and HP, had a market share of 11.7 per cent in the third quarter of 2022 in China. Besides the three leading players of Lenovo, HP and Dell, there are a number of Chinese mainland and Taiwanese players offering competitive products. Compared to smartphones, internet-of-things products and smart cars, personal computers have seen less innovation.

Most of the supply chains that have left China involved relatively simple design and production processes that require minimal research and development and little ingenious product prototyping. The relatively stable nature of these product developments implies networks of suppliers of inputs do not change much.

While personal computers require quite a few parts, it is gradually becoming a commodity product. Replicating or moving the supply chain of personal computers away from China is possible, though this could incur higher costs. Dell’s costs of supply chains set up elsewhere could be 15 to 20 per cent higher than those in China.

Dell might also lose part market share in China. Government and state-owned companies in China will replace foreign-branded computers and software with locally developed products by mid-2024, according to Bloomberg.

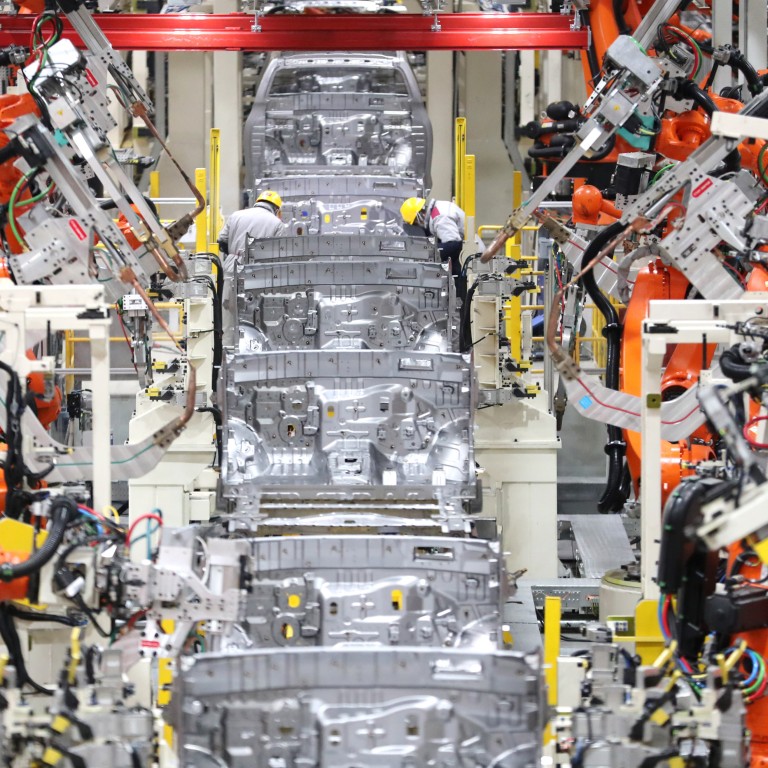

Bosch plans to build a US$1 billion research, development and manufacturing facility for components for new energy vehicles and automated-driving technology in Suzhou.

Doug Guthrie, who led Apple University’s efforts in leadership and organisational development in China, put forth three key reasons in January 2022 why Apple was so successful in building its supply chain in China.

The first is the Chinese government’s ability to move labour around the country to meet the needs of companies such as Apple. The second reason is China’s infrastructure that “ties everything together”. The third is the ability of many Chinese cities to build industrial clusters with vast and complicated networks of suppliers.

These are difficult to replicate. Making this happen requires meticulous collaboration between the local governments, suppliers, logistics companies and key manufacturers.

While this core is being built and strengthened, supply chains in the fringe that comprise of matured and simpler products are being chipped away. Some of them will get replicated somewhere else.

This dynamic process requires continuous adjustments, and China is constantly upgrading its capabilities to keep moving up the value chain despite headwinds such as US sanctions. The higher it goes, the more difficult it becomes for others to replace it.

Instead of taking one data point and projecting it for all industries, let’s take a longer view, revisit Dell’s case in three years from now and see how it will go.

Edward Tse is founder and CEO, Gao Feng Advisory Company, a strategy consulting and financial advisory firm with roots in China.