Advertisement

Opinion | Confused Australia must decide: is China a friend or a foe?

- By extending an olive branch to Beijing to reset economic ties while continuing with its military posturing, Canberra is sending out mixed messages

- Australia must set its own path to reconciliation with China and not let third-party ambitions derail it

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

47

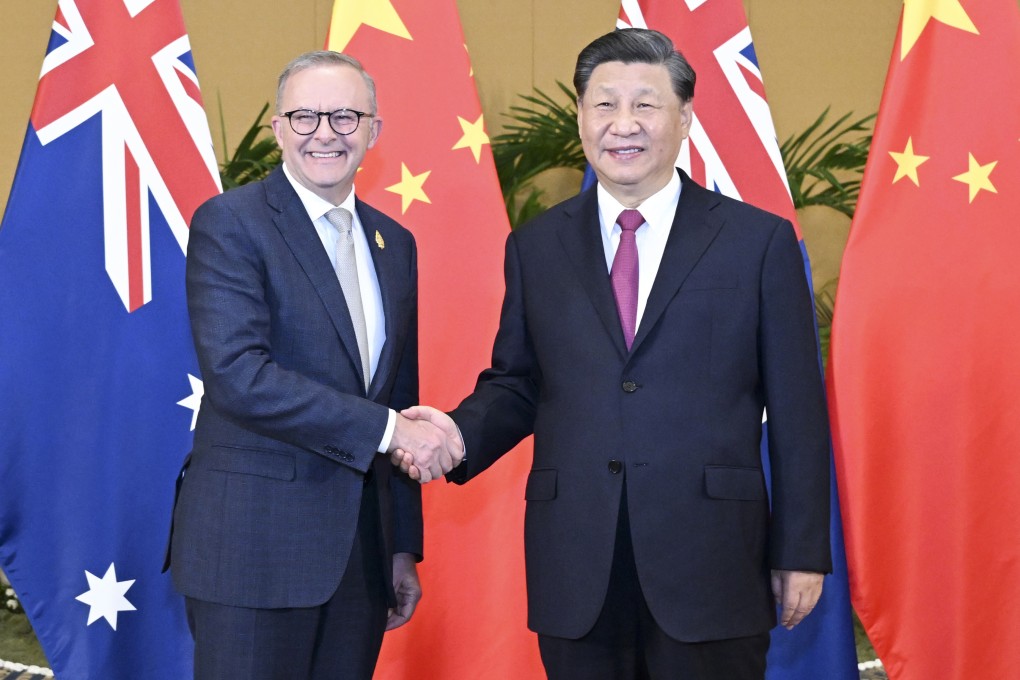

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese backed a joint statement at the recent G7 summit in Japan about de-risking trade with China as his trade minister, Don Farrell, concluded a trip to Beijing seeking to end tariffs on Australian exports due to the country’s posturing against its biggest export partner.

This contradictory approach from Canberra has been a hallmark of its diplomacy with Beijing. On one hand, it extends an olive branch, seeking to cease or de-escalate economic tensions which affect its exports. On the other, it grabs a pitchfork and displays hostility through diplomatic forums like the Group of 7 or militarily, like with the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and Aukus alliance.

This has been exacerbated as Albanese’s government marks one year in office. His strategy towards China was labelled a “reset” but it needs to be more transparent on how Canberra wants to label China: as a friend or a foe.

Advertisement

Politics is in turmoil and Foreign Minister Penny Wong is advocating for peace and cooperation. At the same time, the Department of Defence, under the leadership of Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles, is consistently unveiling new military endeavours in partnership with the United States, explicitly aimed at China.

During her visit to Beijing to celebrate 50 years of diplomatic relations, Wong said “ice thaws, but slowly”. The military posturing and joint statements targeting China could freeze relations again. Not since World War II has Australia’s foreign policy been so military-centric. It is a departure from the decades of diplomatic ventures central to Australia achieving its foreign policy objectives.

Wong’s diplomacy has been a cornerstone of Australia’s diplomatic reset with China. Her actions align with her intentions, re-engaging and stabilising relations in a respectful manner, reflective of her Asian heritage.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x