Why the C919 is more than just an aircraft for China

- With its home-grown passenger jet, Comac is trying to break into a long-standing aviation duopoly, while China hopes to turn a unipolar world order into a more multipolar one

- The C919’s first voyage is a bittersweet success, though, because US-China tensions mean it won’t be able to compete with Boeing and Airbus in their backyard

I myself once doubted whether the C919 would come to fruition. In 2013, when I worked as a consultant for Western companies supplying aviation technology to the C919, I wrote the following in Aviation Week: “I don’t think I’ll live long enough to one day step onto a C919 at Beijing Capital International Airport on its way to Chengdu or Shanghai.”

Chinese engineers who were only familiar with military-related aircraft were confronted with challenges unique to the commercial sector: how to keep down the cost of maintenance and repair, select and qualify foreign suppliers and calculate the total cost of ownership.

Seen in this light, Comac’s accomplishments are remarkable. The state-owned company was established only in 2008, yet it completed in 15 years what it took Boeing almost 40 years to do, even though the latter had a host of previous commercial aircraft designs from which to draw.

For starters, Comac had no reason to abscond with trade secrets when a who’s who of aviation suppliers – such as General Electric, Honeywell and Eaton – were competing fiercely with each other to win its business and secure a piece of what soon will be the world’s largest commercial aviation market. China is expected to purchase more than 8,000 new aircraft in the next 20 years.

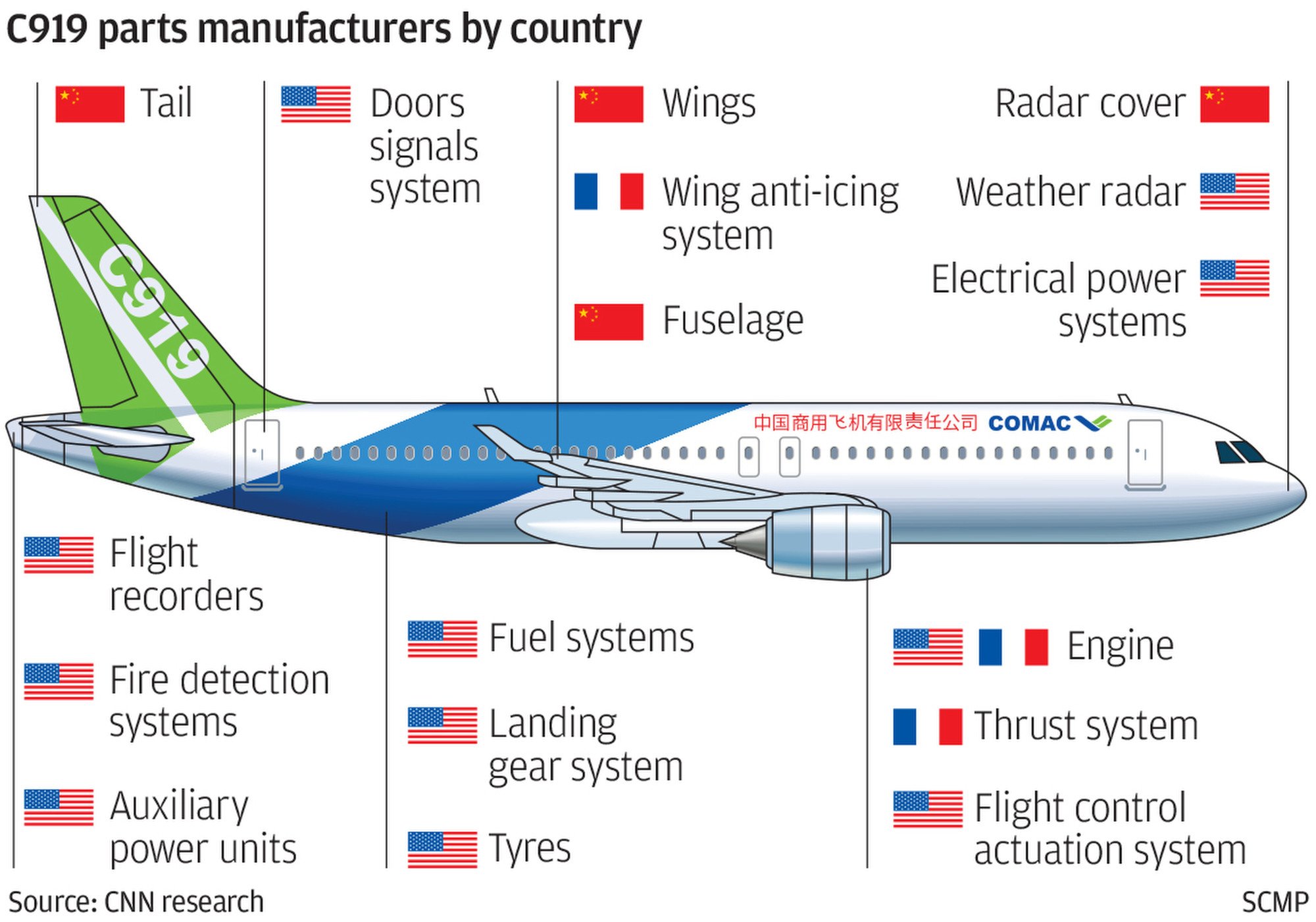

Moreover, Comac has used foreign supply chains the same way its global competitors do. Boeing’s website, for instance, boasts suppliers from across the world. That includes China, which provides horizontal stabilisers from Shanghai, vertical fins from Xian and tail sections and cargo doors from Shenyang.

A Comac executive once told me that the company’s ultimate goal was to compete with Airbus and Boeing in their backyard. That would require obtaining a stamp of approval from the US Federal Aviation Administration, which is an unlikely development given the US administration’s current posture towards China.

Based on its track record, we would be remiss to question Comac’s commitment. In 2014, when Comac was struggling with repeated delays, President Xi Jinping told employees that their work was the cornerstone of China’s emergence as a real superpower. Giving up was not an option and would have been tantamount to a national failure.

In the end, the C919 isn’t just an aircraft. It represents the hopes and dreams of 1.4 billion Chinese people, exemplifying the nation’s transformation from a humiliated former giant to an assertive power that stands on an equal footing with the West. Any further predictions must grapple with that reality.

Stanley Chao has worked in China and the Asia-Pacific region for more than two decades and is the author of “Selling to China: A Guide for Small and Medium-Sized Businesses.”