Advertisement

Opinion | Why not allow Hongkongers to air their views on Chinese University council reform?

- Lawmakers seeking to initiate change through legislation, rather than leaving it to the governing council, should not shy away from having to defend their bill to the public

- A request for a public hearing over the Chinese University bill should be allowed

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

13

The Chinese University of Hong Kong has been making headlines, but not for good reasons, regrettably. As the saying goes, academic politics is the most vicious because the stakes are so small.

Until recently, the effort to reform the university’s governing council has made the news only occasionally. But now, its internal fight that once took place behind the scenes, has erupted into public view, with political heavyweights such as former Hong Kong chief executive Leung Chun-ying and other public figures weighing in.

Punches and jabs are being thrown from all corners. For those of us who have not been following collegiate politics and are not used to this sort of a slug fest, it’s a little off-putting.

Advertisement

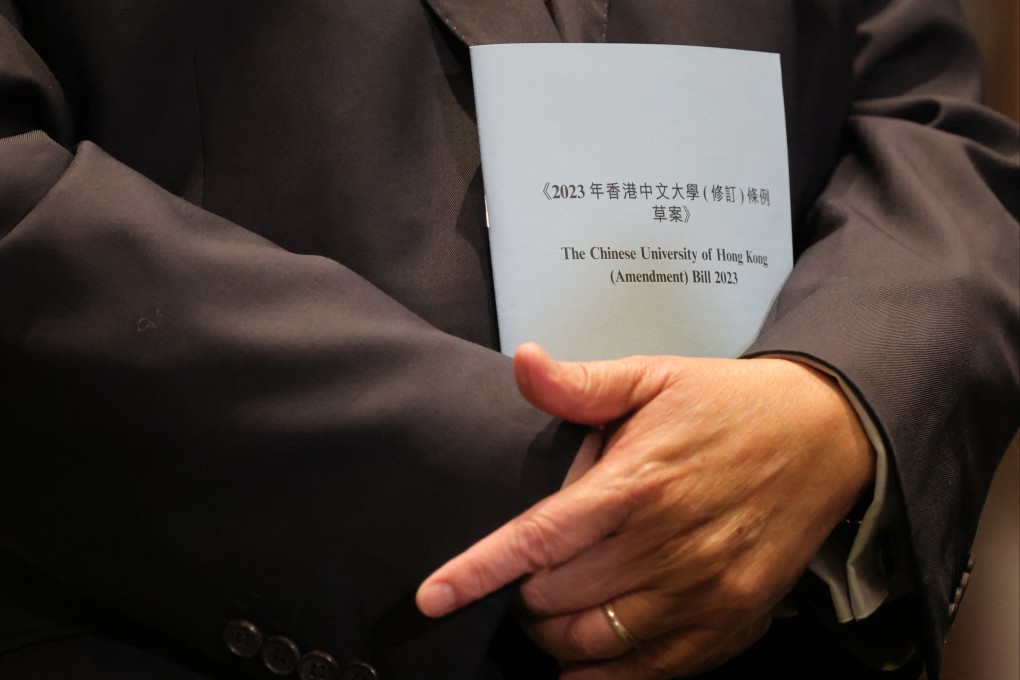

The storm in the college tea cup has become quite a political headache for the government and Legislative Council. At the centre of the controversy is the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Amendment) Bill 2023, a private members’ bill initiated by three lawmakers – Edward Lau Kwok-fan, Tommy Cheung Yu-yan and Bill Tang Ka-piu – who sit on the university council.

Those who oppose the move to restructure Chinese University’s governing body have launched a petition against the bill, even taking out front-page ads in three newspapers last Thursday. More than 1,400 people have signed the petition, including notable public figures such as a former CEO of the Airport Authority, the director of the Hong Kong Palace Museum and a former undersecretary for commerce and economic development.

Advertisement

The deputy head of the Chief Executive’s Policy Unit, Nicholas Kwan Ka-ming, was also a signatory, but he has since withdrawn his support, citing concern that the expression of his personal opinion might be seen as reflecting the government’s position.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x