Advertisement

Opinion | Why tackling the climate crisis requires new rules to keep outer space safe and stable

- The current space governance regime is unsustainable, with vague language and unenforceable terms leaving states to behave as they wish

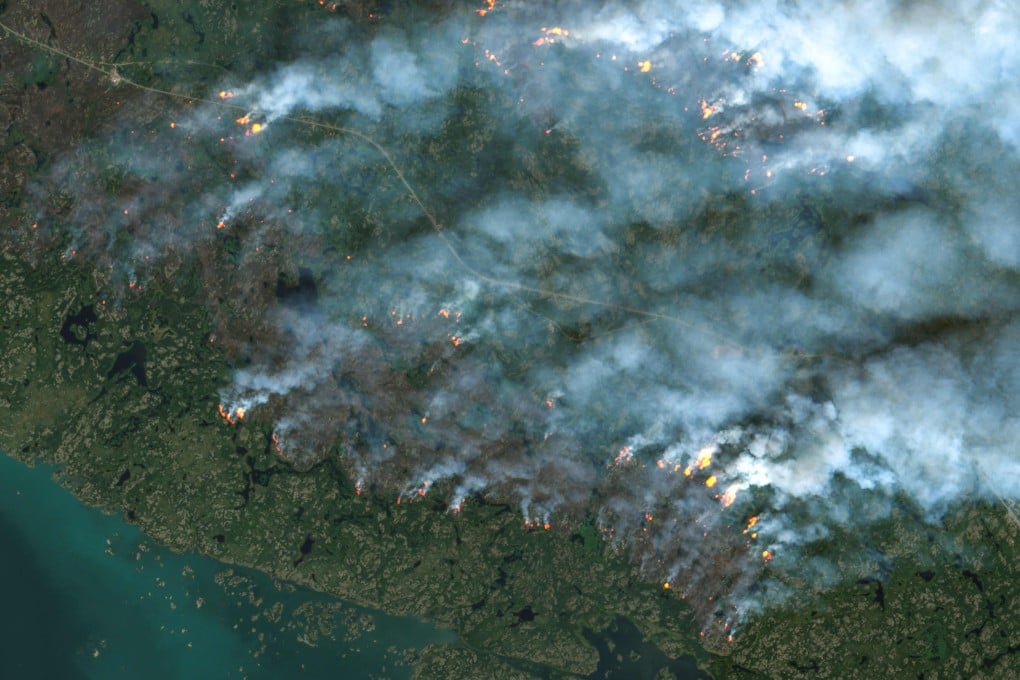

- Many of the variables needed to monitor climate change can only be measured by satellites, so keeping space safe is essential

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

1

The successful deployment of India’s lunar rover last week is a tremendous success for science. The rover, known as Pragyan, will assess minerals on the moon’s surface and study the chemical composition of the soil.

It’s believed that the south polar region may possess water ice below the surface, which could be mined for rocket fuel and life support for future crewed missions. The Indian mission shows how our capabilities within space are expanding rapidly.

This is good news, but in all of the excitement over new missions such as that of the Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft, it’s easy to forget that space governance remains woefully inadequate. There are five international treaties underpinning space law, overseen by the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS).

Advertisement

These treaties lack enforcement mechanisms, making them easy to ignore. Without a new international agreement on space, the world faces growing risks to infrastructure crucial for tackling many problems humanity faces, including climate change.

There are now 77 government space agencies and more than 10,000 commercial space companies. The space economy is worth a staggering US$469 billion, with commercial space ventures accounting for almost 80 per cent of the market. This could lead to 100,000 satellites in orbit by 2030, increasing the risk of debris damaging critical infrastructure.

The uncontrolled re-entry of China’s Long March 5B rocket booster back to Earth last year and Russia’s attack on the Kosmos-1408 satellite illustrate how the current governance structure is unsustainable. Even so, all major space powers claim to support the goal of improving space governance.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x