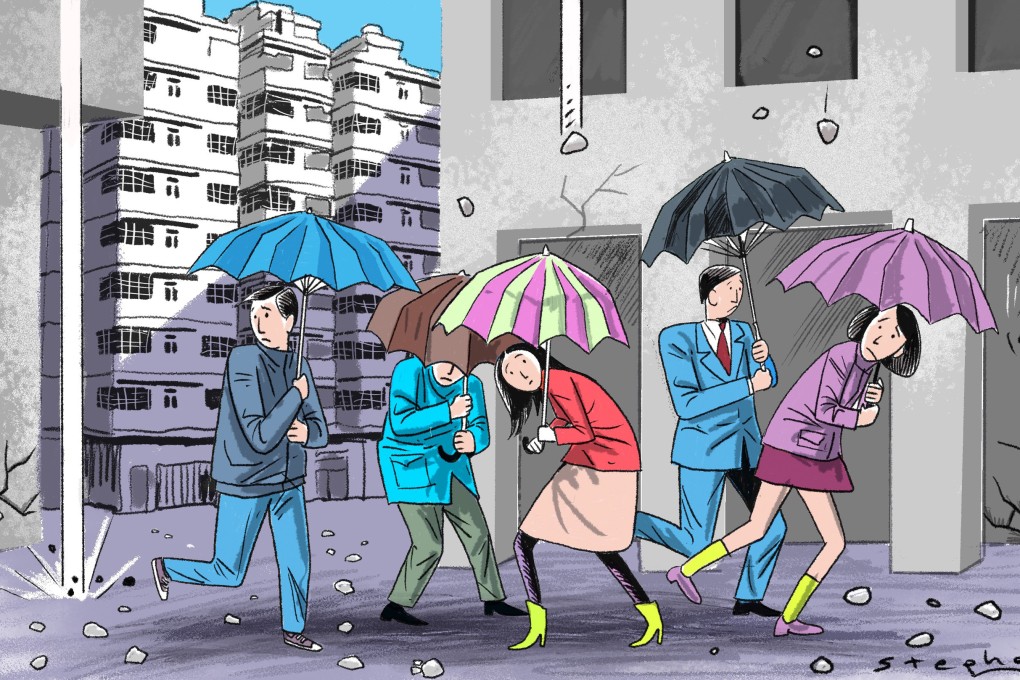

Opinion | Hong Kong must repair its decaying buildings – with public funds if necessary

- Maintaining the city’s ageing buildings is a costly and complex process involving multiple parties

- It is also closely related to urban renewal, and the Urban Renewal Authority must take a lead to improve the living conditions of people in run-down areas

In an architectural history class, my professor noted that architecture was anything but creating artificial built environments, and that our creativity would always submit to the power of nature. This is why the best works that stand the test of time are vernacular architecture that draws from the native context and serves local needs.

In an urban environment that demands density and efficiency, rarely do we come across this kind of architecture in cities. Instead, most modern buildings are built with concrete and steel because they are cost-effective, structurally sound, durable and safe against fire hazards.

Concrete is strong in compression and steel performs well in tension, which is how they work together in spanning floor slabs between beams and columns. Spalling, or deterioration, happens because the thin protective layer of concrete at the bottom of the steel is stretched under tension.

The buildings will not crumble because the compressed concrete above and the tensioned steel bars still work in sync to hold up the slabs, but spalling should be repaired to prevent further deterioration.