Advertisement

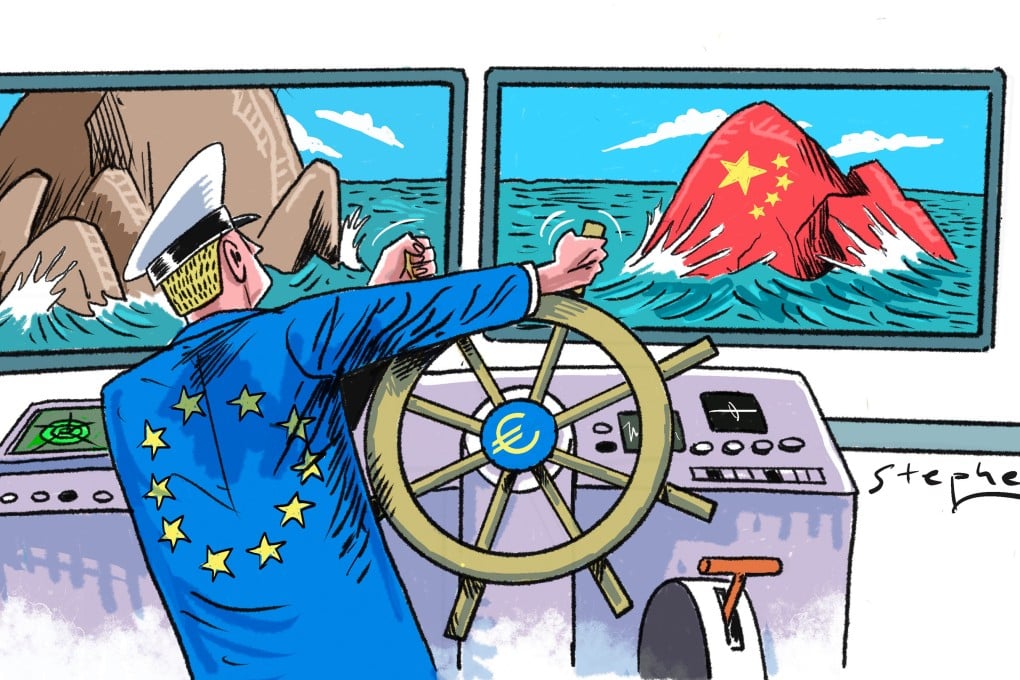

Opinion | In focusing on China, Europe risks missing true ‘de-risking’ dangers

- Risks from China must be put in perspective against tensions in northeast Asia, from Taiwan to the Korean peninsula, and an increasingly isolationist and protectionist US

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

1

“De-risking” has come to dominate European discourse on China and Russia. To its advocates, it reflects a calibrated compromise between European desires for strategic autonomy, the enduring alignment between Washington and Brussels, and the growing convergence in economic interests between Europe and China.

The term is best defined as the recalibrating and diversifying of trade relationships to minimise the downsides of disproportionate dependencies.

Brussels has announced four priority areas in which Europe would seek a critical review and potential reduction of partnerships with China: artificial intelligence, semiconductors, quantum technology and biotechnology. As important as minimising undue dependence may be, the European Union should seize the opportunity to develop a more holistic understanding of risk.

Advertisement

Firstly, the EU can put into perspective the scale and potential repercussions of its growing economic ties with Beijing. The increase in European net imports from China has benefited European consumers while threatening to drive out of business many producers in Germany and France, with competition particularly fierce in electric vehicles.

Much dialogue on reducing exposure to China has focused on allegedly unfair Chinese trade practices and “economic coercion”. The worry is that China would weaponise its investment and ties within strategic sectors in Europe, and its heft in advanced manufacturing to extract geopolitical and strategic favours from the EU.

Advertisement

Yet this need not be a zero-sum game. Ventures between Chinese and German companies, such as BMW Brilliance Automotive, have long flourished to mutual advantage. For European companies in China, building up greater local expertise through employing local staff, advisers and joint venture partners is also vital for competitiveness within China.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x

.png?itok=bcjjKRme&v=1692256346)