Advertisement

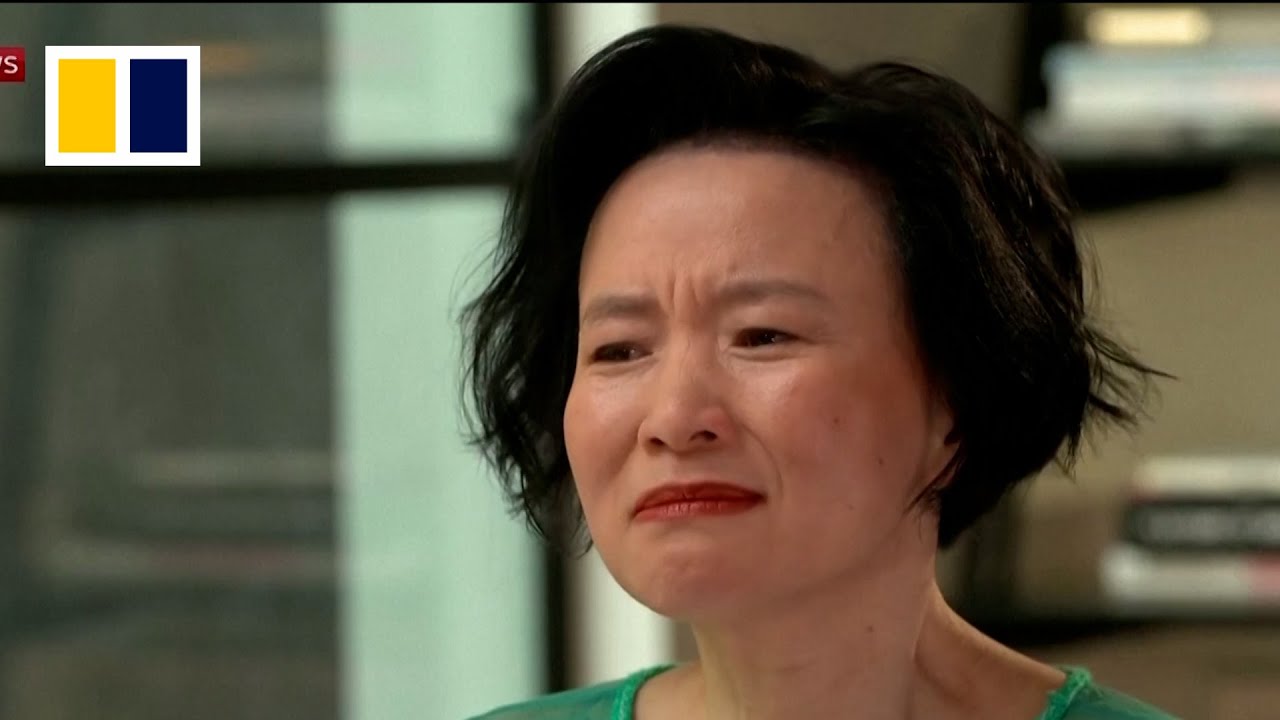

Opinion | In China policy, Albanese’s hands are tied by Australia’s populist forces

- In the new normal in liberal democracies like Australia, a fearful majority can be mobilised against indigenous rights or a rational China policy

- The Australian PM has to keep his objectives for his upcoming China trip modest, as it will be judged at home through the populist filter of fear

3-MIN READ3-MIN

12

The upcoming visit to China by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is now even less likely to feature any grand gesture in international relations, following a devastating referendum defeat in Australia over the weekend.

This is despite the fact that the visit will mark the 50th anniversary of a very grand gesture, the visit to China in 1973 of Albanese’s fellow Labor prime minister, Gough Whitlam. That visit signalled a more independent Australian foreign policy. It created the conditions for half a century of mutual prosperity, with Australia becoming a key supplier to China of resources and food, and an attractive education, tourism and immigration destination.

Things have changed in recent years. The Australia-China relationship took a nosedive after a series of provocative words and actions by the previous Australian government, met by Chinese sanctions on Australian wine, beef and lobsters.

Advertisement

As a parting gift, the previous Australian government secretly abandoned decades of consensus on continental defence strategy, to lock Australia into a massive investment in forward-deployed nuclear submarines to bolster the US Pacific Fleet.

Albanese should have been able to use the 50th anniversary of Whitlam’s China visit to outline a new ambitious vision of cooperation for peace, prosperity and people-to-people friendship. But that is unlikely due to the shift in security strategy, which Albanese has endorsed, as well as some disturbing trends on the home front.

Advertisement

The link between China policy and a recent referendum on constitutional recognition of Australia’s First Peoples might at first glance appear to be tenuous. Yet the referendum result reveals the very deep cleavages in Australian society that constrain Albanese from developing an independent and ambitious foreign policy in the national interest.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x