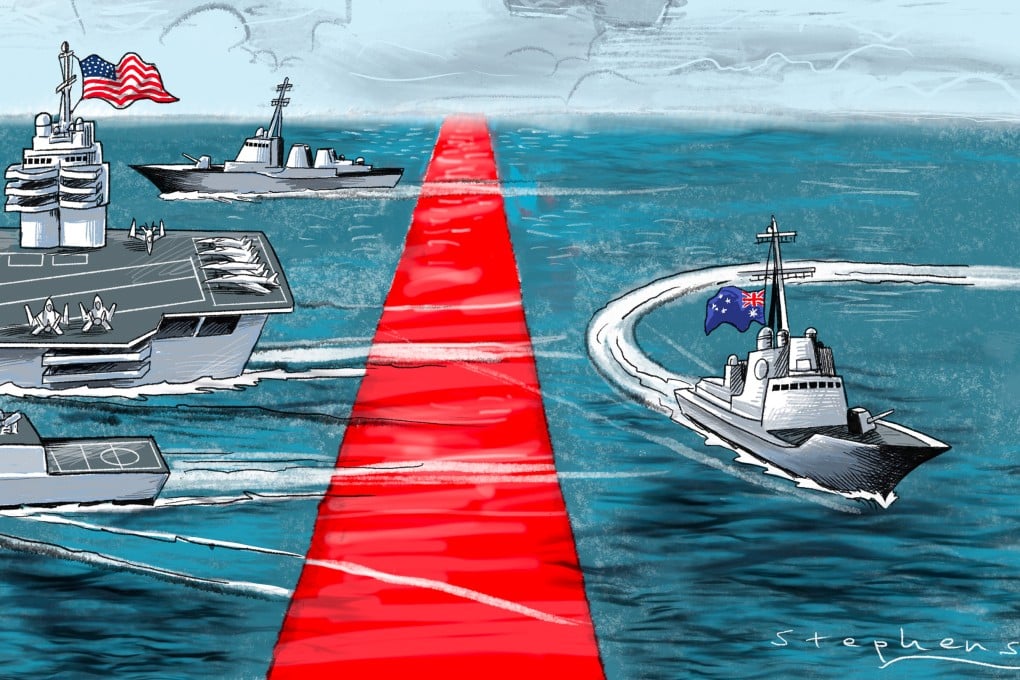

Opinion | Why Australia is wary of supporting US-led Red Sea operations

- Indo-Pacific commitments aside, Australia is seeking to avoid yet another open-ended military commitment in the Middle East

- Above all, Canberra is mindful that such a move could further alienate voters amid low public trust in government, declining social cohesion and increasing polarisation

In response to the recent US request for Australian support in Operation Prosperity Guardian – to combat Houthi-led attacks on shipping in the Red Sea – Canberra declined to deploy its warships or planes, citing resource constraints and the complicated Indo-Pacific strategic environment. However, it agreed to triple its troop deployment to the US-led naval force.

To address what Canberra called China’s unprecedented “military build-up” without “transparency” in the “strategic intent”, Australia has called for a focused force and threat-based planning.

Australia expects the United States to understand its reluctance to deploy warships in the Red Sea, and has emphasised its Western Pacific priorities to show alignment with American interests over China.