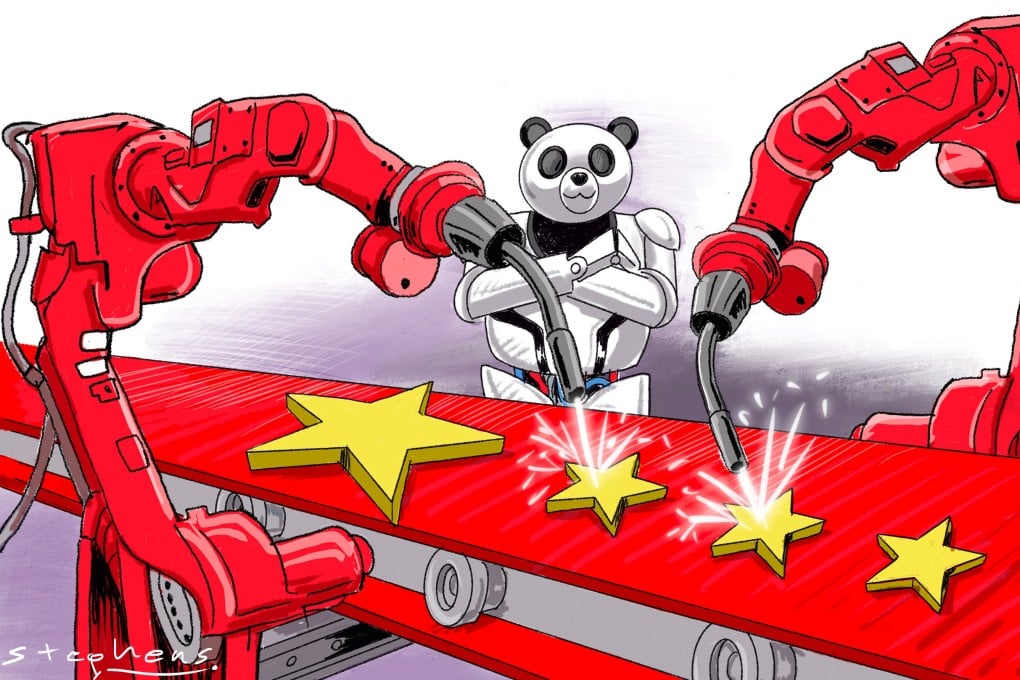

Opinion | Greying China is poised to reap a new economic dividend: robotics

- As the population shrinks, China is looking to compensate for a dwindling youth dividend with robotics. Already the world’s largest market for industrial robots, it is now a manufacturer to be reckoned with too

Looking back on China’s reform and opening up, its success was predicated on two pillars: institutional deregulation and the demographic dividends of a young and growing population. Such dividends, however, are evaporating at an accelerated pace.

The apex of China’s demographic dividends was probably around 2010. Data suggests the nation’s workforce as a share of its population rose from 58 per cent in 1979, when economic reforms started, to a high of about 74 per cent in 2010.

Things, however, took a turn for the worse after that. Young migrants, reluctant to take on back-breaking work like their parents, began to leave the factories in droves between 2010 and 2014. During that period, traditional manufacturing hubs like the Pearl and Yangtze river delta regions experienced an exodus of labour and widespread hiring difficulties.