SCO leaders hail unity yet struggle to find common ground at Samarkand summit

- As Xi, Putin and other Eurasian leaders gathered for a meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, promises of stronger economic ties and a shared global agenda could not conceal political differences, especially over the war in Ukraine

The format makes for an uneasy alliance, united predominantly by common economic interests. This was reflected in the resolutions passed at the summit and the agreements forged on the sidelines, which largely focused on economic cooperation.

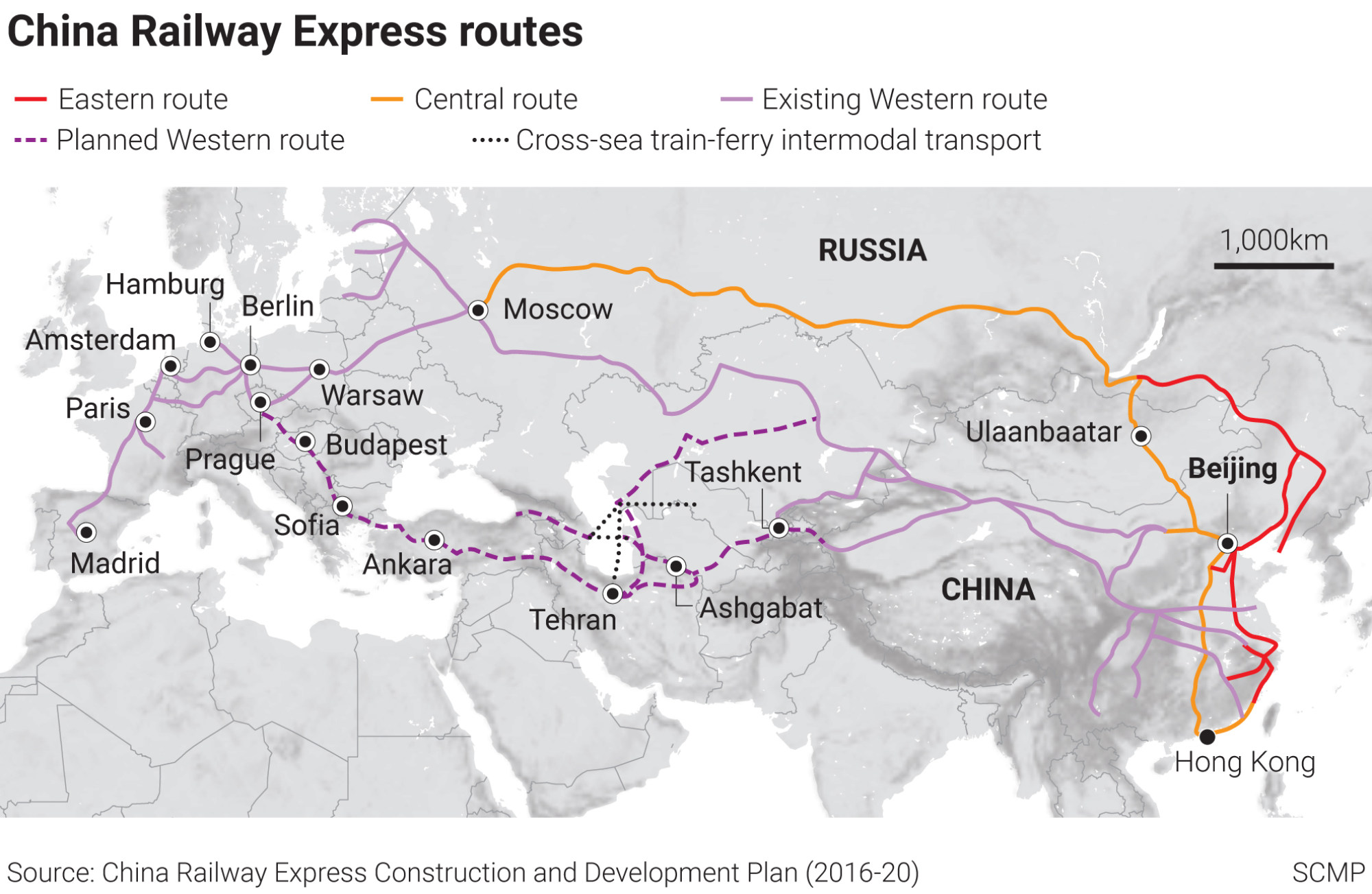

Plans for the railway were originally drawn up in 1997, but the project was repeatedly shelved due to Russian opposition. Now, however, Putin appears to have dropped his objections. The agreement on the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway therefore seems symptomatic of Russia’s weakened position in Central Asia.

Evidence of Russia’s waning influence was plentiful at the Samarkand summit.

But not all leaders insisted on distancing themselves from Russia. Ebrahim Raisi, the president of Iran – which was admitted as a full member of the SCO on Friday – told Putin that countries which face US sanctions can work together to “overcome many problems and issues and become stronger”.

Tehran called on the SCO to help it avert Western sanctions imposed over its nuclear programme. Some members even adopted a road map for increasing their reserves of each other’s national currencies in mutual settlements and cutting down on the use of the US dollar, but the idea was not universally embraced, according to the Samarkand Declaration.

“We must grasp the trend of the times, strengthen solidarity and cooperation, and promote the construction of a closer community of destiny with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” Xi said. He emphasised the need to jointly safeguard security and development interests and prevent outside forces from staging “colour revolutions”.

This idea of overlooking members’ internal differences to turn the SCO into a counterweight to the West seems to have gained traction within the group.

The Samarkand Declaration, signed by all leaders at the end of the summit, announced that “based on their similar views of the current regional and international agenda, the Member States reaffirm their commitment to the formation of a more representative, democratic, just and multipolar world order”.

Xi welcomes a weakened Putin at SCO summit

The SCO is now the world’s largest regional organisation, accounting for around 60 per cent of the area of Eurasia and half of the world’s population. With Egypt and Qatar becoming dialogue partners, and Bahrain, Kuwait, Myanmar, the Maldives and the UAE all expressing an interest in taking part, the format is eyeing rapid expansion.

As India prepares to take up chairmanship of the group next year, expect the members of the SCO to stick to questions of trade and condemnations of Western overreach. Finding common ground beyond those familiar walls will be a tough ask.

Theo Normanton is the Moscow correspondent for bne IntelliNews. He covers current affairs in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States, with a particular focus on economics and markets