Advertisement

Opinion | Did the SCO summit signal a Pax Sinica emerging in Central Asia?

- Global ambitions aside, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation remains key to tackling regional unrest and economic uncertainty

- Amid Russia’s struggles in Ukraine, China is likely to play a greater role in Central Asia, although Beijing’s influence will be limited by distrust among the populations of these countries

3-MIN READ3-MIN

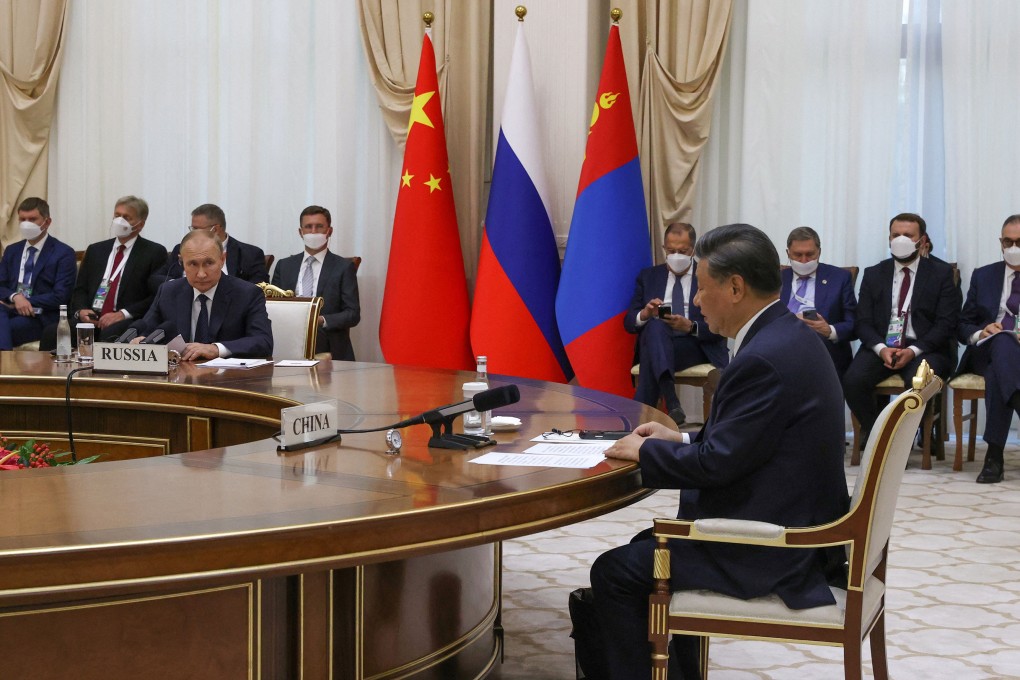

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) heads of state summit in Samarkand last week drew much international attention, not only because it marked Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first foreign trip in more than two years, but also because it was the regional grouping’s first in-person gathering since the outbreak of the Ukraine war.

Not surprisingly, the focus was on China and other member states’ position on Russia’s “special military operation”. Much as the case was during Russia’s conflicts with Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, the SCO neither endorsed nor opposed Moscow’s action, though Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed his concerns to Russian President Vladimir Putin. The Russian leader also acknowledged that Xi had “questions and concerns” about the war.

Meanwhile, border clashes between Kyrgyz and Tajik troops continued even as the presidents of the two Central Asian states attended the summit. Notwithstanding the Samarkand Declaration’s pledge to create “a more representative, democratic, just and multipolar world order”, maintaining stability in a region in motion remains the SCO’s top priority for now.

Advertisement

Since it was founded in 2001, the SCO has been the subject of speculation and imagination. Some see it as the “Nato of the East”; others dismiss it as a “hollow talk shop with little practical follow-through”. Both perspectives, however, overlook the organisation’s role as a political framework acceptable to all, an institutional platform where member states have equal right to voice their concerns and participate in regional governance.

The principle of non-intervention and consensus-based decision-making have certainly constrained the SCO’s impact both on regional security – for example, it lacks the mandate and capabilities to respond to emergencies such as the riots in Kazakhstan in January – and on regional economic cooperation, wherein Beijing’s proposals to establish a free trade area and a development bank have in effect been shelved.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x