How cooperation on marine protection between China and Southeast Asian nations can reduce regional tensions

- Marine protected areas offer a potential solution to many of the threats facing the region’s oceans, including illegal fishing and habitat destruction

- They are also a non-threatening way for countries that have competing claims in the South China Sea to come together and work for mutual benefit

A recent study in the journal Science on marine conservation confirms that although ocean ecosystems are complex and dynamic, the spillover benefits at Hawaii’s largest fully protected MPA supports the increased number of two migratory species, bigeye and yellowfin tuna.

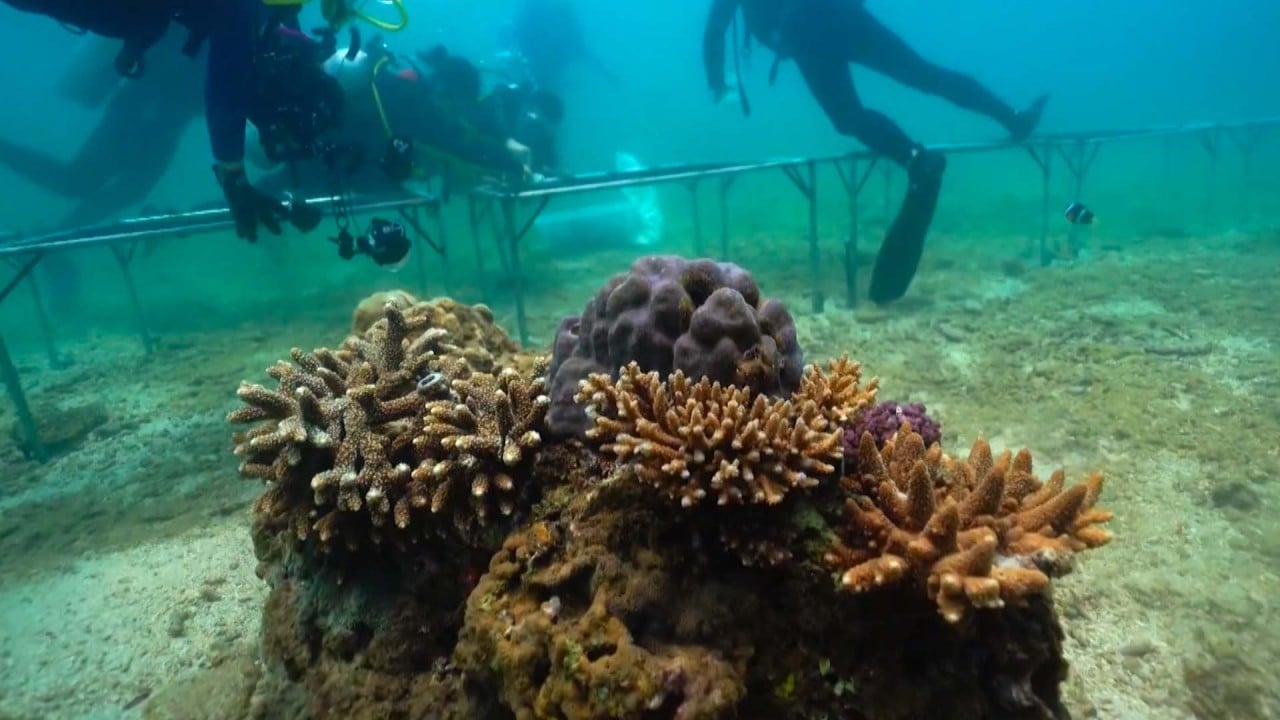

China knows it is in dangerous waters since it has entered the “ecological conservation redline”, which reflects Beijing’s urgency to protect marine spaces from development. In the past two decades, it has lost vast swathes of its mangrove cover and more than 80 per cent of its coral reefs.

A 2021 research article in Science Advances states that China’s MPAs “protect rare or endangered species and ecosystems. They are no-take, meaning any extraction of fish or other living resources is illegal.”

According to SDG Plus, the top challenges for creating MPAs in the world include poor prioritisation of marine areas to protect; faulty implementation of protection measures; unequal distribution, with developed countries leading in the creation of MPAs; and, loss of income for the local communities because of the creation of no-take zones.

In a regional sea with complicated territorial and maritime disputes like the South China Sea, the development of a regional network of MPAs with marine peace parks as components offers the possibility of decreasing tensions and enhancing cooperation between claimants.

There are policy advances derived from cooperative marine science projects, which offer benefits from the establishment of new MPAs in the South China Sea. For instance, at the regional level, a first common fisheries resource analysis relating to skipjack tuna in the South China Sea was completed in September 2022 with the support of the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and the participation of fisheries scientists from China, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam.

In addition, the Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance is establishing a blended finance facility with Blue Finance to implement sustainable, revenue-generating initiatives in pilot programmes planned in Indonesia and the Philippines.

The second phase could include additional participants such as China and other Southeast Asian coastal states, which could translate into more data for a South China Sea-based network of MPAs.

These projects are stellar examples of the compliance with Article 242 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea that asks states and international organisations to promote international cooperation in marine scientific research for peaceful purposes.

While there remain plenty of obstacles for regional marine scientific research cooperation, the prospects for networked MPAs could ensure peace-building and a surplus of goodwill and a fish savings account for future generations.

James Borton is a senior fellow at Johns Hopkins/SAIS Foreign Policy Institute and the author of Dispatches from the South China Sea: Navigating to Common Ground.

Vu Hai Dang is a research fellow at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.