Article 23: concern over Hong Kong’s subsidiary legislation understandable but misplaced

- Subsidiary legislation is often found in both common law and civil law jurisdictions. Its purpose is to provide details and guidelines in relation to matters under the primary legislation – but never to create new offences

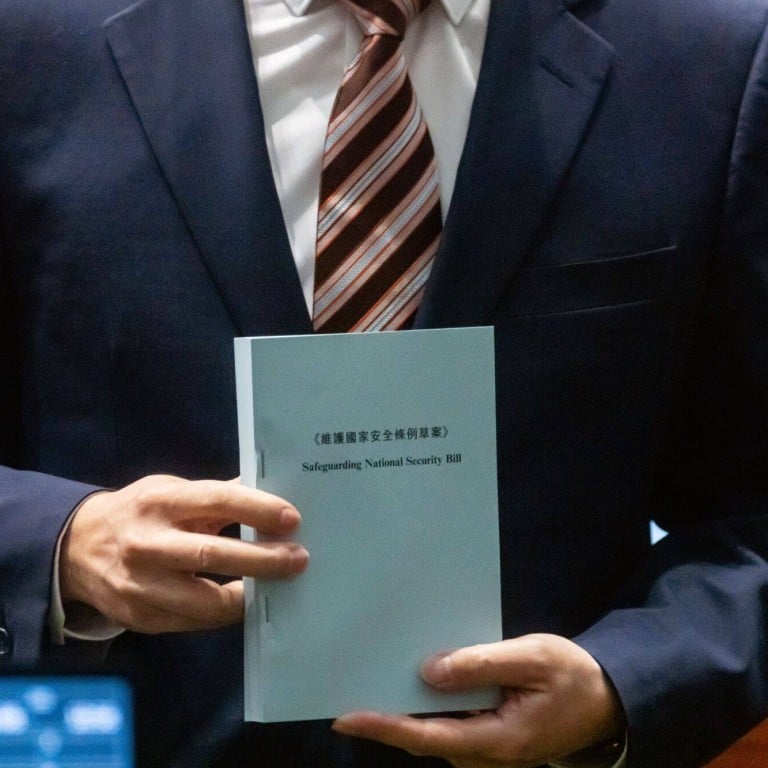

After the Hong Kong government’s announcement that it would enact Article 23 legislation, discussions on the proposed bill were relatively calm and rational.

It is thus somewhat surprising that legislators and the government alike seemed to be unaware of such sensitive issues and unprepared to offer detailed explanations.

Be that as it may, the concerns of the public are somewhat misplaced. Subsidiary legislation is a form of secondary legislation often found in both common law and civil law jurisdictions. Its purpose is to provide operational details, guidelines and procedures in relation to matters provided under the primary legislation but never to create new law, let alone new offences.

If you fall foul of the subsidiary legislation, you may be punished for non-compliance with the regulation but never for being guilty of the crime specified under the primary legislation.

What this means, as explained by the courts, is that no subsidiary legislation can overreach or exceed the ambit or effect of the primary legislation. Section 35 of that ordinance further provides that any subsidiary legislation must be subject to the approval of Legco, which may by resolution amend the whole or any part of the subsidiary legislation.

The nature and effect of subsidiary legislation did not change after 1997. Indeed, the use of subsidiary legislation to supplement the workings of the primary legislation continues today; for example, more than 20 pieces of subsidiary legislation have been drawn up so far this year.

In relation to the proposed amendment to the Article 23 bill, there are at least three other rather important points to remember. First, any subsidiary legislation must be read and understood to be subject to the same requirements of the primary legislation itself. What this means is that the basic principles set out in Part 1 of the bill, that individual rights protected under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the principle of rule of law must be respected, shall also apply to any subsidiary legislation.

Second, the Hong Kong national security law is a superior law passed by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and under that law there is already the power to make subsidiary legislation. It is extremely unlikely that any subsidiary legislation made under the Article 23 bill could change or replace or be inconsistent with the national security law or any subsidiary legislation made under that law. It also follows that any subsidiary legislation made under the bill cannot enlarge or restrict the legal effect and ambit of the law.

Third, under our common law system, any subsidiary legislation is always subject to the supervisory oversight and control of the judiciary. If any subsidiary legislation were to be made without the power given under the primary legislation, or contrary to any provision of the same, the courts could strike it down by judicial review.

In the circumstances, any concern that the proposed amendment giving power to the chief executive in council to make subsidiary legislation under the bill might lead to any enlargement of the power or effect of Chapter V of the Hong Kong national security law is without legal or factual basis and entirely misplaced.

Ronny Tong, KC, SC, JP, is a former chairman of the Hong Kong Bar Association, a member of the Executive Council and convenor of the Path of Democracy