Advertisement

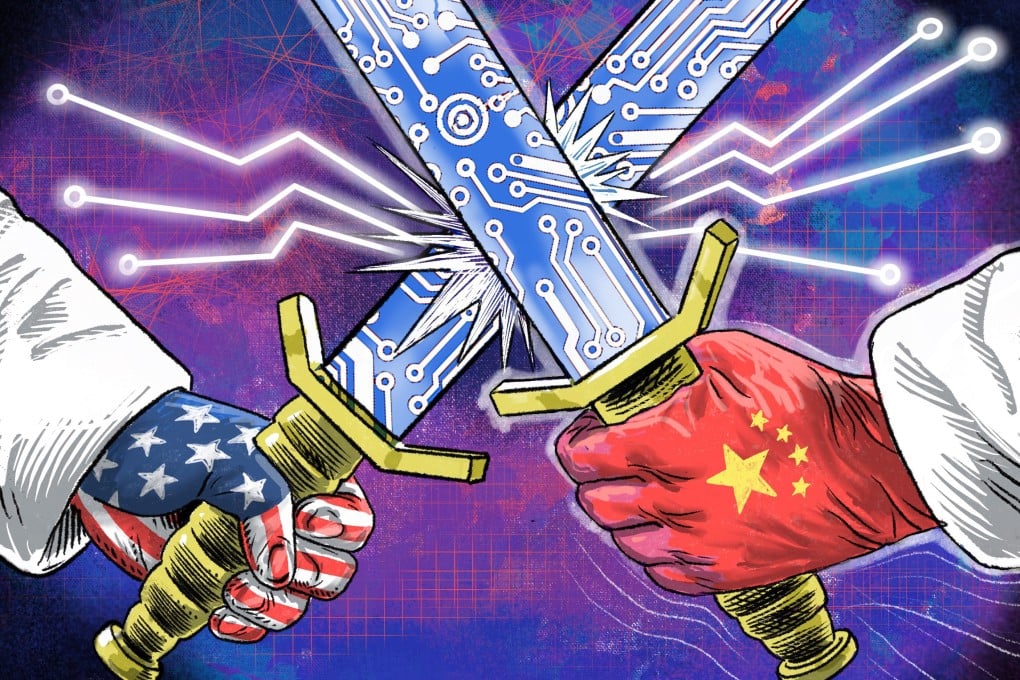

Opinion | China must face up to its weaknesses to escape the ‘middle technology trap’

- Amid a tech war with the US, China is boosting its war chest by 10 per cent and focusing on basic research, moves that could establish its tech supremacy

- But internal challenges remain, including an unbalanced tech work culture, low cultural appetite for risk and a higher education geared towards practical engineering rather than basic science

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

4

What do the outcomes from the “two sessions”, China’s highest political meetings, mean for the US-China science and technology rivalry? After all, this area is the new battleground and the defining point of US-China relations in the 21st century. Can the meetings help China escape the “middle technology trap” and leapfrog towards tech supremacy, if it is not already there?

Since the tech war launched by former US president Donald Trump and amplified by his successor Joe Biden, China seems to have been in defence mode, launching limited counterstrikes.

The meetings’ strategic emphasis on artificial intelligence, biotech, new energy vehicles and space tech has somewhat surprised the nations that have dominated in these domains for decades. But this could be China’s answer to the industrial revolution it missed.

Advertisement

The planned 10 per cent jump in science and tech spending to 370.8 billion yuan (US$51.5 billion) this year is the largest percentage increase for any major area of government spending, including the military, education and diplomacy. Some 98 billion yuan has been earmarked for basic research, up 13 per cent from last year.

The key message in this budget is the sense of crisis, determination and momentum-building. China realises it can no longer rely on being able to buy from the best suppliers in the global tech supply chain but will have to master its own destiny.

Advertisement

One pillar of China’s industrial and technological success has been its policy of affordable innovation. This involves a focus on affordable goods and technologies that cater to the needs of untapped market segments or to latent demand (for example, the middle and lower middle classes in Western countries and the Global South), offering new options (such as more affordable mobile phones, cars, computer chips and equipment) and slowly capturing the market share as the innovation component increases.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x