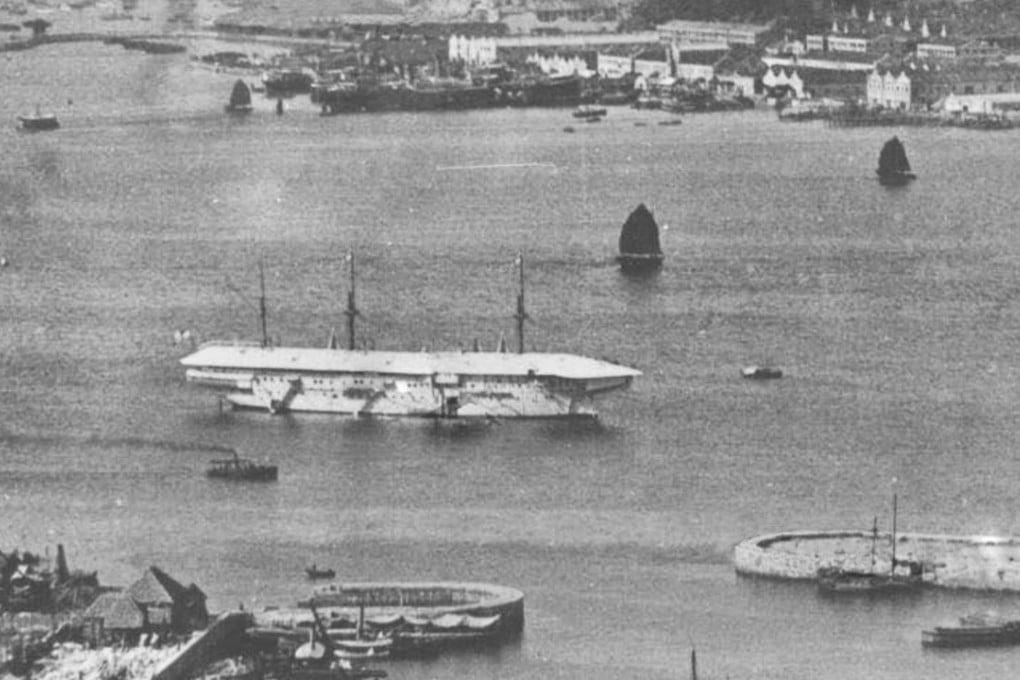

How China uses shipwrecks to weave a history of seaborne trade that backs up its construction of a new maritime Silk Road

Out of nowhere, China has become the Asian leader in marine archaeology, a quest that serves both a cultural and a political purpose; there’s no such impetus in Hong Kong, despite its own long maritime history

Shipwrecks are becoming a hot topic in Asia, particularly in China, where maritime archaeology did not exist until the 1990s, but is now regarded as a national priority.

This week, more than 100 of the region’s leading marine archaeologists from 23 nations convened at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum for the Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage. At the opening reception on Monday night, the meteoric rise of China as a force in maritime archaeology was one of the popular topics of discussion.

Divers off Hong Kong’s southernmost island find cannon and anchors which may be remnants from 1944 shipwreck

“Now, China has some of the most respected marine archaeologists and one the best resourced capabilities in the world,” says maritime archaeologist Dr Bill Jeffery, who helped organise the event.

The scale of that capability is revealed at an exhibition called “Sailing the Seven Seas: Legends of Maritime Trade of Ming dynasty”, which opened at the Hong Kong Heritage Discovery Centre this month. It includes hundreds of archaeological finds from two Ming dynasty shipwrecks, the Nan’ao No 1 and the Wanli.

They range from exquisite ceramics to tiny bone dice, perhaps used by bored sailors on long sea voyages. Both wrecks were recovered by Chinese archaeologists.

In an attempt to include Hong Kong in what is called “the vibrant scene in navigation and maritime trade”, ceramics from the same period unearthed in the city’s waters are also displayed, though none of these come from shipwrecks or even from under the water.