Hard lessons for creator of Little Fighter 2 and other would-be Hong Kong games developers

Many Hongkongers want to get into game development but it’s a business where popularity doesn’t always mean revenue, especially in a small market like Hong Kong. More are succeeding, though

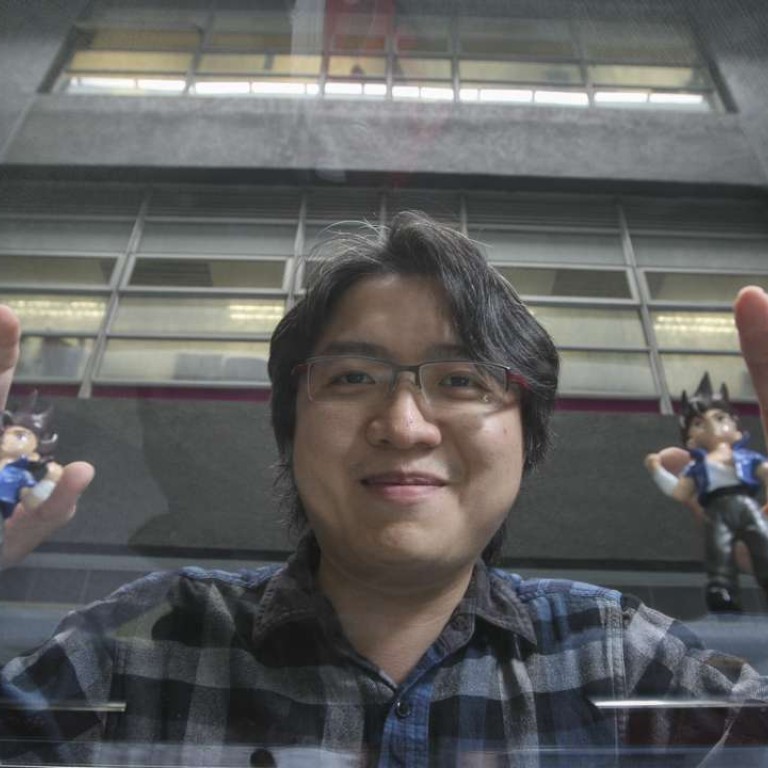

While they were studying computer science at Chinese University of Hong Kong in 1999, Marti Wong Kwok-hung and Starsky Wong created a side-scrolling game called Little Fighter 2. It was so popular the university servers crashed, overwhelmed by the sheer number of downloads.

“On the bus, I remember hearing kids talk about the characters and strategies, which made me very happy,” Marti Wong says.

For three years, he adds, Little Fighter 2 remained among the 10 most searched games on Yahoo, while bootleggers sold copies of the free game in Mong Kok. But although the game and its subsequent iterations garnered solid followings, Marti Wong never made enough to pursue his dream of becoming a full-time developer. And there lies the rub.

The global digital games market is enormous – worth an estimated US$91 billion in 2015 and forecast to keep growing till at least 2018, according to market researchers Newzoo.

And, like Wong, many young people are as keen to create these digital games as they are to play them.

But it’s a tough environment that requires developers to think strategically if they are to succeed, says Simon Wong Man-fai, an executive committee member of the Hong Kong Digital Entertainment Association. Being popular isn’t enough; they need to find a way to generate revenue from the game.

“There’s not a lot of room for growth in Hong Kong. Companies can survive, but it’s a hard business,” says Simon Wong, a 15-year veteran in the industry. “Now the young people really want to get into this field and they’re not afraid to say it.”

However, he warns: “Don’t think it’s a lot of fun. Playing games and making them are very different.”

As founder and director of Gamemiracle, Wong began producing popular horse-racing games in the early 2000s for arcades, PCs, and now for mobile devices.

The key to success, he says, is figuring out how to charge users even before designing a good game.

Wong routinely plays the most popular and lucrative mobile games until he feels compelled to buy something in the game. For example, he’ll play Candy Crush until he feels the urge to spend money for an extra move.

Why are there a lot of games that are fun but don’t make much money? That’s because they start with the gameplay. You make a great game, but then you have payment points that people just don’t get to.

He doesn’t pay but makes a note of the point in the game where he has this feeling , and repeats the process with the other popular games.

So when designing a new release for Gamemiracle, he will map out all possible payment points and then create a game concept to wrap around those points.

“Think of it as digging a lot of holes in the ground. Each hole is a payment point, and game design is about designing a path so that people fall in these holes,” Simon Wong says.

“Why are there a lot of games that are fun but don’t make much money? That’s because they start with the gameplay. You make a great game, but then you have payment points that people just don’t get to. Now I think about it backwards.”

“The games that make it in Hong Kong understand this concept; they focus on how to use psychology to get people to fall in these holes; that’s why they make money.”

“This is a very important concept that I tell people when I give talks. It’s not guaranteed to work but it makes it easier to break even.”

A Chinese University report on creative industries in Hong Kong found that the city had some 36 sizeable game development and publishing companies in 2010, accounting for total investment of about HK$132 billion.

Some commentators derided it as being very similar to Puzzle & Dragons, a popular Japanese mobile game, but that hasn’t stopped Tower notching up some 18 million downloads since.

Simon Wong says developers don’t have to innovate too much with payment systems; in fact being too clever can backfire as happened when game publisher Blizzard Entertainment introduced an auction house system for its highly anticipated Diablo III role-playing game.

The move, which allowed players to spend real money to buy more powerful gear for characters instead of earning them through gameplay, put off many gamers and Blizzard was forced to axe the system in 2014.

But the Gamemiracle boss also points to Little Fighter 2 as a popular release that features excellent gameplay but lacks a good business model.

Hero Fighter X, a later mobile version which he spent two years working on, has had some commercial success but he says the revenues are still insufficient to fulfil his dream of becoming a full-time developer.

Marti Wong now works on freelance IT projects, but he hasn’t given up on Little Fighter 2.

“I really like this game, and I can’t bear to just abandon the project. It’s like when you’re waiting for a bus; you wait for 30 minutes and there’s still no bus, but you don’t know if one will arrive two minutes after you leave.”

But he’s taking Simon Wong’s advice and thinking about how to market and make money, even though he doesn’t entirely embrace the idea as a gamer.

“I don’t feel comfortable with this, but I know this is a business model that works. I feel like this is amplifying the bad side of

human nature. But I can’t be

too negative about this because I may have to accept this model some day. But now I want to focus on doing something that I think is right. Maybe this is naïve.”

The reverse engineering approach works for mobile games because the Google and Apple app stores track games by revenue and retention rate, Marti Wong says, but they can’t measure how much fun the game is.

“This means that publishers have to play the system, because if your game is ranked higher, you can save a lot of money on marketing,” he says.

Even so, gameplay doesn’t have to come second.

It targets “hardcore players”, Tsang says, and good gameplay keeps them around.

Also a computer science student at Chinese University, the 23-year-old developed Dynamics with a few friends as part of an incubator scheme and set up C4Cat in 2014 to market and distribute the game.

When the game took off, Tsang decided to take a break from his studies to work on the company.

Dynamix has been downloaded a million times so far, and brings in sufficient advertising and in-app revenue to support a team of eight people who work out of a small office in Tuen Mun.

“We’ve done pretty well among the smaller outfits in Hong Kong,” Tsang says. “Some industry colleagues tell us ‘Hong Kong is counting on you’. They make it sound so dramatic.”

Dynamix has also broken into the Japanese and Korean markets, which augurs well for the future.

If a game only makes it in Hong Kong, “you’re just

fighting for a tiny slice of the pie”, says C4Cat art director Kong Kwok-lee.

“If we make a world-class game that gets [into] the Japanese, European or US market, that’s the way to succeed.”

Dynamix’s popularity with gamers abroad has come as a surprise to Tsang, who recalls how his team had to rely on Google Translate in the early days, when they started to receive queries from players in Korean, French and other languages.

While C4Cat has received HK$150,000 annually from the government’s Technology Start-up Support Scheme for Universities since 2014, Kong reckons appointing university instructors with more real-world experience would give a bigger boost to the industry.

Yim Chun-pang, a senior teaching fellow at City University’s School of Creative Media, suggests the government consider helping local game developers promote their games overseas.

Last October, the British government introduced a £4 million (HK$44 million) fund to support independent game development, citing the success of home-grown titles such as Tomb Raider, Grand Theft Auto and Batman: Arkham Knight.

And Dynamix from C4Cat is just the sort of product that could do even better with overseas promotion, says Yim, an experienced game developer himself.

“Everyone agrees that Hong Kong still has some catching up to do compared to the US or Europe, but it doesn’t mean that Hong Kong lacks the talent.”