Inking differently: the Chinese artists breaking new ground in one of the most traditional of art forms

Young ink artists are taking a traditionally minimalist, derivative genre in new directions by inserting contemporary references in classically drawn works or transplanting the form to other media

If the second edition of the Ink Asia art fair proved anything, it is that the centuries-old genre is alive and well, and thriving in today’s hectic, digitised world. The fair, which wrapped up at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre on December 18, saw 50 generously sized booths filled with all manner of ink art, and ink-inspired art.

Visiting the fair was a pleasant experience. Compared with the fly-in, fly-out nature of Art Basel Hong Kong, Ink Asia is an oasis of calm; the largely local crowd preferred more leisurely browsing. But behind the display of elegant brushwork lurks the same existential fear about the prospects for other traditional art forms. Prices for so-called “contemporary ink art” – a discrete category international auction houses have promoted heavily in the past few years – have surged. But even the most dedicated Chinese ink artists are fearful that the genre is not on a firm enough footing for new works to withstand the test of time.

There are similarities with contemporary classical music, where mould-breaking compositions struggle to assert themselves in the programming for mainstream concerts in which composers long dead still loom large. In shuimo, meaning water and ink, the forms laid down by ancient Chinese ink painters are still the gold standard.

A video tour of Ink Asia

“Tang paintings were the starters used for brewing. Song paintings were the wine. Yuan paintings were great vintages and everything since is watered down, with more water added as the years go by,” said Huang Binhong, a painter and art historian active in the Republic of China, in a brutal, and much cited, put-down.

“Up until his death in 1955, a lot of shuimo paintings were simply copies of what people did in the past. It is a common practice even today. It goes all the way back to the famous literati painters in the Song dynasty, who were all amateurs: they were government officials who were also poets and calligraphers. Many didn’t really know how to paint, so they copied from the great masters and gave the scrolls to their friends, who would say they were very good,” Liu says during his visit to Ink Asia.

Artists ... owe a duty to society. They must have attitudes. Otherwise, they cannot make art

Things started to change in the 1950s and 1960s, when a group of artists turned the experience of living outside China into an opportunity to look at ink art anew. Zhang Daqian, Lu Shoukun, Chao Shao-an and Liu, who fled the artistic confines of communist China after 1949, still observed the core values of shuimo – the materiality of ink and paper, a sense of detachment derived from a culture steeped in Buddhist and Taoist philosophies – but they were also informed by the New Culture Movement of the early 20th century and started to incorporate Western influences into the Chinese art form.

Half a century later, many artists from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan are eager to take over that baton. They include the likes of Xu Bing, Gu Wenda and Chui Pui-chee, who see in calligraphy a rich seam to mine for new ideas. Others, such as Lau Hok-shing and Yang Yongliang, transplant traditional forms in paintings to alternative media such as sculpture, photography and video.

Meanwhile, the gongbi artists adopt the meticulous, fine lines of realistic Imperial court paintings and insert contemporary references, such as the Hong Kong streets in Barbara Choi Tak-yee’s silk landscapes.

The range is impressive. But compared to other contemporary art, such experimentation may seem rather anodyne and safe.

Traditional ink art is not rooted in realism and is not known for being confrontational or direct. Rather, it is long held to be the visual manifestation of the artist’s own spirituality.

“Chinese paintings have been seen as tools since the Tang dynasty – tools for promoting a harmonious Confucian society,” said Wong Xiangyi, a young ink artist from Malaysia who wants to challenge conventions but has a deep respect for the subtle qualities of ink and the possibility of experimenting with different types of traditional craft paper. Even prominent anti-establishment artists such as Bada Shanren and Shi Tao in the Qing dynasty coded their despair in symbolism but kept up the idyllic front – partly to avoid persecution.

More recently, there is a fashion for so-called abstract contemporary ink artists who merge the philosophical appeal of Chinese minimalism with Western conceptualism. But a growing number of artists are calling for a shift in mentality.

He is best known for his provocative performance art, such as “Binding the Lost Souls: Huge Explosion (1993)”, in which he spent 17 days wrapping 10,000 bricks that had fallen off a section of the Great Wall of China with red ribbons. But he has also addressed political issues in his ink paintings. “Bird in the Sky Above Tiananmen Square” (2007) has no bird, a reference to both the pollution in Beijing and the loss of innocent lives on June 4, 1989, he said.

Beijing gallery owner Ami Li has other concerns about the genre. She says more serious academic research is needed on the development of ink art. For example, some may disagree that contemporary ink art is anything other than a continuation of what the previous generation started in the 1950s, while others may argue that subcategories such as urban ink are distinct movements in themselves.

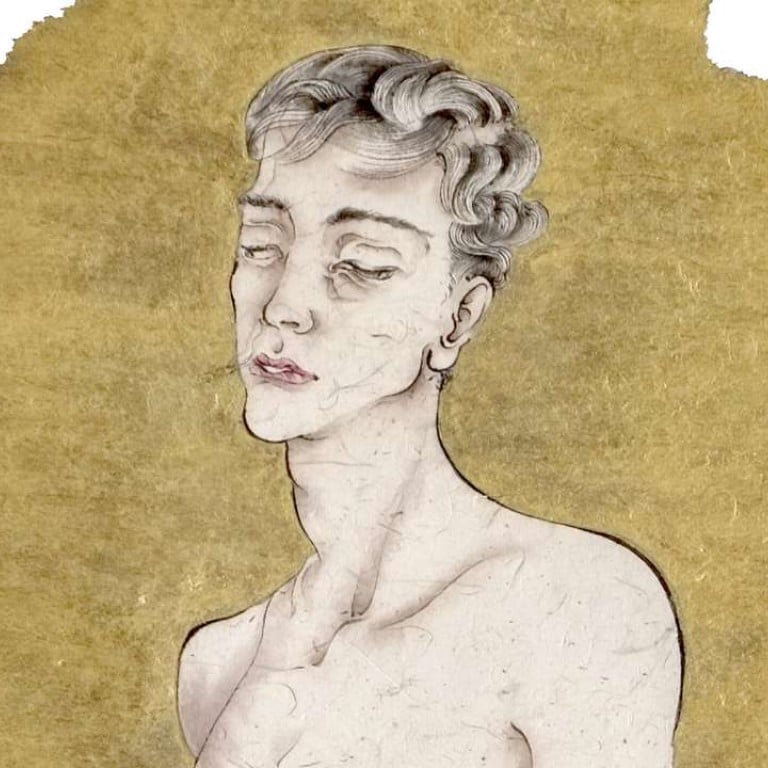

I want to challenge tradition by presenting the interaction between beautiful men on paper, something rarely seen in shuimo

She also thinks the art market has wielded too much influence lately and that this has led to a surfeit of derivative works and too much so-called conceptual art by people who can’t paint.

“The market has cooled and it is quite a good thing for artists. The good ones can pause to think about their work rather than give the market what it wants, and artists will stop following the ones who sell well,” she said.

Wong, who received a solid grounding in technique at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, is one of very few young artists who are really pushing the boundaries of what can be said in Chinese ink art.

She identifies as a fujoshi, a Japanese terms for women who find an escape from rigid social norms in manga – such as Boy’s Love, about relationships between handsome, androgenous men – and appropriated the subculture to radicalise traditional ink art.

She is currently holding her second exhibition in Hong Kong, which features paintings of semi-naked young men in gongbi style on traditional Chinese xuan paper.

“I want to challenge tradition by presenting the interaction between beautiful men on paper, something rarely seen in shuimo, which after all is dominated by generations of men thoroughly tamed by patriarchal values. Even portraits by women artists tend to be made for the male gaze. That’s one reason why I refuse to paint women – I don’t want to be complicit in further objectifying women,” she says.

She is pleased with the approach so far. The visual accessibility of this most “polite” genre helps to lure people in. “Some galleries have insisted on putting up a ‘mature content’ warning for my work, but when they don’t, I have seen schoolchildren studying the paintings and really loving them.”

Wong Xiangyi: Whispering Void, Artify Gallery, 10/F Block A, Ming Pao Industrial Centre, 18 Ka Yip Street, Chai Wan. Tue-Fri 10am-7pm, Sat 11am-7pm, until Feb 18, 2017