Hong Kong Chinese art exhibition examines tension between ideology and the individual

Dancing dissected frogs, neon-lit face and body piercings, stiff formal dancers and abandoned nightclubs feature in ‘After Party: Collective Dance and Individual Gymnastics’ at Blindspot Gallery

Roland Barthes, the French cultural theorist, spent three weeks in China in 1974 as part of propaganda tour organised by Beijing, and he appeared to have sulked through most of it.

Reacting to the cliché-spouting guide’s comment that “Chinese gymnastics” (which probably meant tai chi) had benefits “for body and mind”, Barthes entertained himself by jotting down in his notebook mens fada in corpore salop (a dull mind in a slutty body), misquoting the Latin phrase for “a sound mind in a sound body”.

That entry in his book Travels in China wasn’t directed at the formulaic collective dancing that he witnessed with great distress in the country’s schools, factories and public squares, but it somehow goes with his observation of how the dancers moved with hysterical passion while being the frigid, passive instruments of ideology.

Barthes’ notes are the starting point for an intriguing exhibition about the tension between ideological control and the individual will.

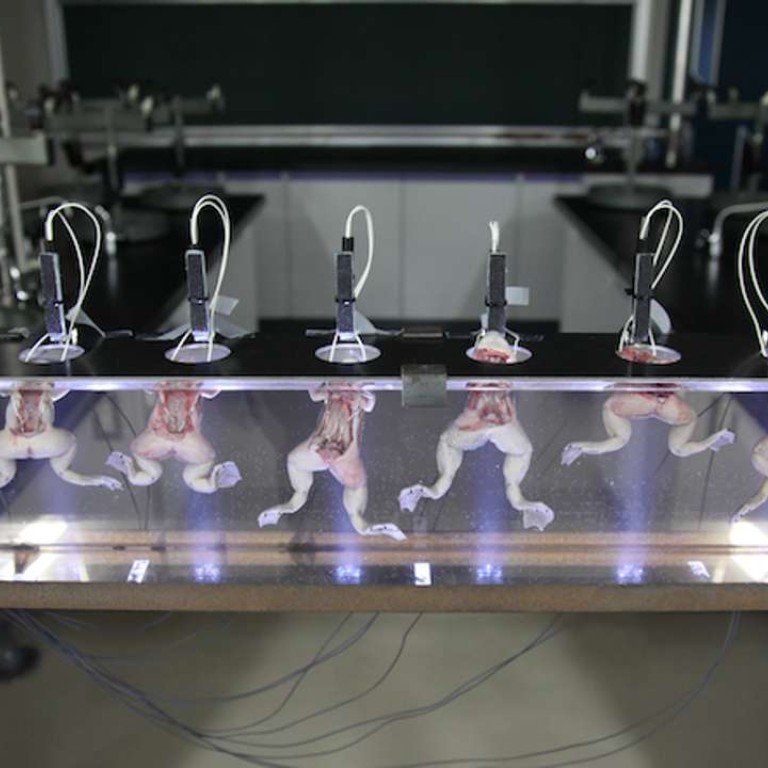

Some of the video images featured in “After Party: Collective Dance and Individual Gymnastics”, appear to mock, as Barthes did, the deadening effect that politics had on dance. Reanimation!Underwater Zombie frog ballet! by Lu Yang shows a row of dissected frogs performing a morbid dance as their dead muscles are stimulated by electric currents.

In a section of Hao Jingban’s Off Takes, a middle-aged couple show off their ballroom dancing skills with the precision and dispassion of automatons. In another scene, the narrator explains how collective formal dancing – or “social dancing”, as it is referred to in Chinese – was encouraged by the Chinese Communist party at specific moments to project an image of an optimistic, energetic and forward-looking country, such as after the party came to power in 1949 and in 1979, when the economy welcomed international investment again.

As Hao’s couple dance in an empty hall, the narrator tells the story of a young ballet dancer whose promising career was curtailed by the Cultural Revolution. Suddenly, the dancers’ formal stiffness no longer looks ridiculous. Instead, it becomes a symbol of unbending artistic conviction.

In The Pink Detachment, New York-based video artist Jen Liu presents a surreal reinterpretation of the Cultural Revolution model ballet The Red Detachment of Women. The young peasant girl who fled an evil landowner to join the Communist revolution in the original is now a worker in a hot dog factory, trapped again by the capitalist system. Meanwhile, a dancer moves with an unstoppable exuberance despite bearing, literally, the weight of progress on her back: a set of steps filled with the crushed bones of either dead pigs or exhausted workers.

“The light running through is romantic in a way, but also represents pain. That’s what intimacy is. The light also represents a rhythm – like the rhythm in a dance – that brings us all together,” says Hu.

If only Barthes could see this.

“After Party: Collective Dance and Individual Gymnastics”, Blindspot Gallery, 15/F Po Chai Industrial Building, 28 Wong Chuk Hang Road. Tue to Sat, 10am-6pm. Ends Mar 4