Homegrown Hong Kong: the wholesome story of Vitasoy

Started in 1940 as a way to fight malnutrition among Hong Kong’s growing immigrant population, Vitasoy has gone from strength to strength, and remains a quintessential part of the city’s identity

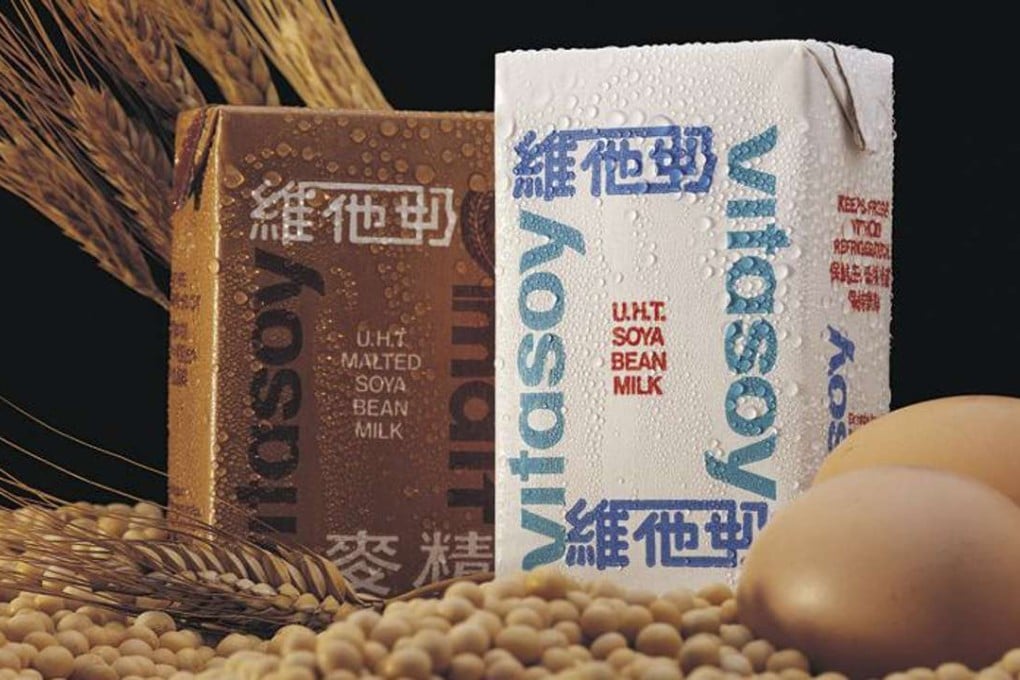

Like many Hongkongers, I find it impossible to remain impartial when it comes to Vitasoy. Years ago, when my wife and I lived in Montreal, we made regular trips to Chinese supermarkets to stock up on cartons of malted soy milk and lemon tea. For her, it was a taste of home. For me, it evoked the city that had captivated me since my first visit.

We aren’t alone. Since it was introduced in 1940 by Lo Kwee-seong, Vitasoy has become one of those quintessential Hong Kong brands whose products are caught up in the city’s pop culture and collective memory.

“Childhood in a box” is how the company’s distinctive soy milk is described by Bourree Lam, a Hong Kong journalist now based in New York.

Others love the seasonal warm soy milk sold in glass bottles. “One of my favourite things to do in Hong Kong’s short winter is to buy a glass bottle of warm malted Vitasoy from the cart,” says food writer Janice Leung Hayes.

But Vitasoy is not simply nostalgia. It’s one of a few classic Hong Kong brands, such as Lee Kum Kee or Wing Wah Bakery, that have managed to become international successes without losing touch with their local identity. And it’s doing well: Vitasoy’s revenue grew 10 per cent last year as consumers shunned syrupy soft drinks for those made with natural ingredients.