Can VR and 3D mapping save China’s cultural history from tourists, earthquakes and climate change?

Technology is being used to digitally preserve Dunhuang’s Mogao Caves as mass tourism takes its toll, while drone footage and photos are helping groups such as CyArk create 3D models of heritage sites across the globe

This is where China begins. The Mogao Caves, which straddle key points on the Silk Road in China’s western Gansu province, are as precious as they are delicate.

Also known as the Thousand Buddha Grottoes, they form a system of 492 temples near the city of Dunhuang that contain some of the finest examples of Buddhist art in China, some dating as far back as AD366. Between them the caves contain some 45,000 square metres of exquisite murals and 2,415 coloured sculptures, many fashioned from clay, wood and straw.

How China can reclaim its lost cultural heritage

It may sound intriguing, but that’s the problem. Much of the artwork on the cave walls is deteriorating, a problem attributed to a surge in tourist numbers at the site, which became a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1987.

“Carbon dioxide exhaled by the visitors builds up in the caves, resulting in an increase in temperature and humidity, which further degrades the murals and sculptures,” says Wang Xudong, associate director of the Dunhuang Research Academy.

But experts have come up with a potential solution: digital mapping to create virtual reality (VR) caves that can be visited by anyone, anywhere.

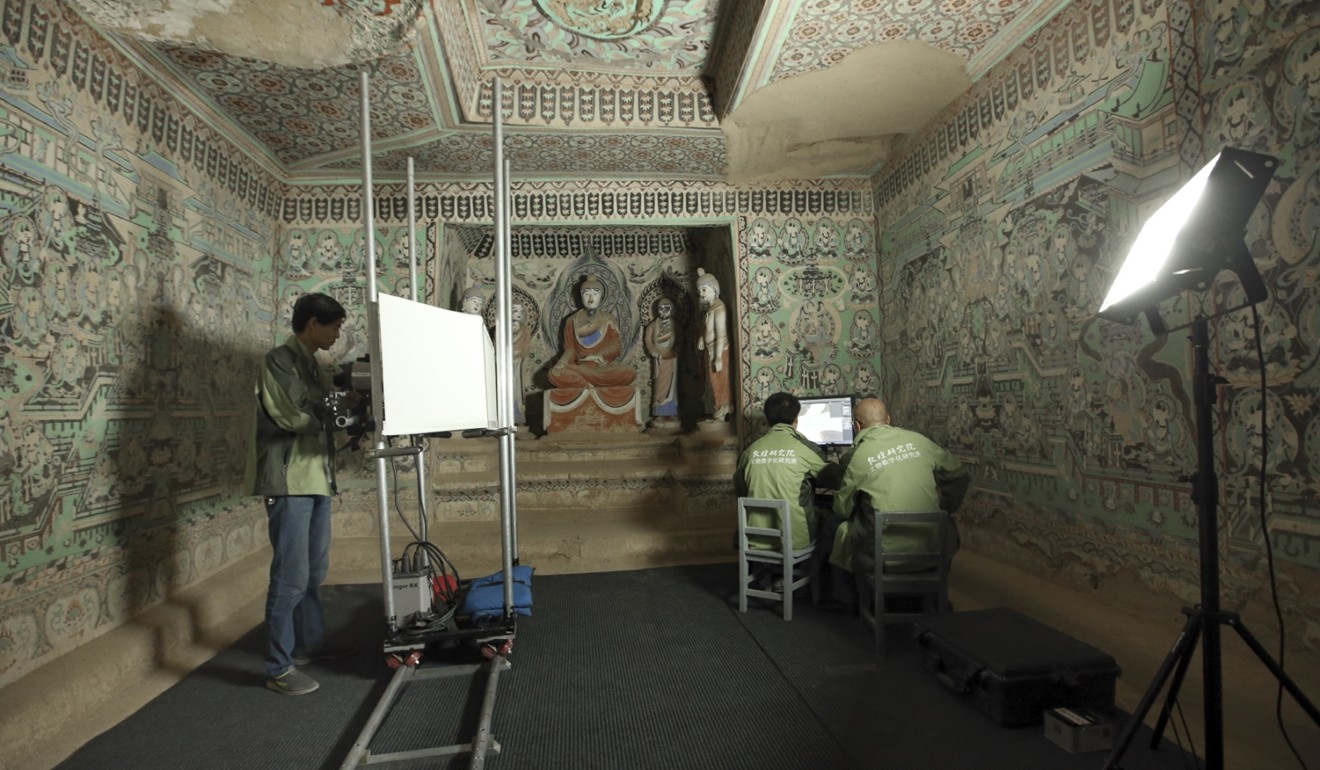

A joint initiative between the Dunhuang Research Academy, the China Dunhuang Grottoes Conservation Research Foundation and America’s Seagate Technology, the project involves a range of advanced techniques and technologies.

“We’re using techniques for photography, computer image processing technology, 3D scanning and reconstruction, and panoramic roaming technology to digitally protect the site,” says Ding Xiaohong from the Dunhuang Research Academy.

Lidar (light detection and ranging) laser scanning is being used to bounce light off objects to measure exact distances, while 360-degree panoramic images are being produced using fisheye lenses.

The resulting 3D mapping data is perfect for reproduction in VR, but it’s a time-consuming process. “It depends on the size of the caves. Normally it takes several months to complete the 3D scanning and reconstruction [of one area],” Ding says.

This is the same “big data” challenge that so many industries now face: scientists are capturing, processing and archiving data on a whole new scale thanks to recent advances in technology.

“The power and value of data is infinite,” says Sandy Sun, vice-president and general manager for Asia-Pacific and China sales at Seagate, which handles the project’s data storage side. “With the digital protection and storage of precious data, we hope that the splendid Dunhuang culture can be enjoyed not only by our generation, but it can be handed down to later generations. This is what we can, and should, do as a ‘sci-tech’ organisation.”

The scientists at Dunhuang are hoping to create detailed, immersive VR experiences, both online and on-site, so that visitors won’t feel the need to visit as many caves, or stay inside them for as long. However, Ding admits that despite the extra carbon dioxide that visitors create, tourism is a double-edged sword. “Tourism can help propagate Dunhuang culture, and enables more people to realise the importance of cultural relics protection,” he says.

There are few more important places in China’s cultural history. “Dunhuang is incredibly significant for China and the wider world – this is the city at the mouth of the Silk Road,” says Thomas Bird, the East Asia-based co-author of Dunhuang – A City on the Silk Road. “This is where Chinese envoys left to war with barbarian tribes, or foster trade relationships with Central Asian states, and where silk and other commodities that made Han China so rich left the ‘celestial realm’ for distant markets, some as far as Rome.”

Dunhuang is also where foreign religions entered China; the caves’ Buddhist artworks document China’s centuries-long infatuation with the Indian spiritual practice. “This is world-class world heritage, no less,” Bird says. “It’s visual evidence of cultural cross-pollination between two of the world’s oldest civilisations. And it’s all captured with beautiful artistry by a hundred nameless monks.”

Dunhuang is usually reached by flying via Xian or Lanzhou. A ticket allows visitors to enter eight caves during the peak season and 12 during off-season. About 70 caves are open to the public at various times, leaving many permanently out of reach from visitors to control preservation. Ding says that a good way to protect the caves is to travel during off-season, to ease the environmental pressures the caves face during peak season.

We created 3D models [of the Monumental Arch of Palmyra] using photos … It would have been possible to use LIDAR … but we didn’t have that luxury because it had already been reduced to rubble

It isn’t just tourism that threatens heritage sites: earthquakes, climate change and conflict are among many other reasons to pursue digital preservation. Seagate, for example, has also helped build digital museums such as of the Ancient Tea Horse Road Museum in Lijiang, which tells the history of routes that once linked Yunnan with Tibet, India and Southeast Asia. The company has also helped the Peking Opera Theatre of Beijing in its digital preservation efforts.

But Seagate’s most high-profile project is a two-year collaboration with CyArk, a US non-profit organisation that is attempting to digitally preserve 500 cultural heritage sites. CyArk has so far created digital records of more than 200 sites in 40 countries, including Angkor Wat in Cambodia, Sydney Opera House in Australia, and the temple city of Bagan in Myanmar (where the damage wrought by earthquakes last year served as a strong reminder that such sites need to be digitally preserved sooner rather than later.)

Temple city Bagan after the earthquake: what’s still to see and where to go

CyArk’s most recent project was digitally preserving Wat Phra Si Sanphet in the historic city of Ayutthaya, about 85km north of Bangkok in Thailand. Ayutthaya, also a Unesco World Heritage Site, flourished from the 14th to the 18th centuries as the second capital of the kingdom of Siam, and was one of the planet’s largest urban areas at the time. However, it was destroyed by the invading Burmese in 1767, leaving behind only stone monuments.

While CyArk’s project in Thailand has seen the use of Lidar, it has largely involved the collection of photographs by hand-held cameras and aerial drones, which can be turned into photorealistic 3D models. Archaeologists and architects can often get just as much information from photos as more complicated methods – even from snaps taken by tourists.

Photos were recently used to create a highly detailed 3D model of the Monumental Arch of Palmyra, a 1,800-year-old Roman arch in Syria that was destroyed by Islamic State militants in 2015. In a show of defiance, and to illustrate how important it is to digitally preserve heritage sites, a replica of the arch was carved out of Egyptian marble using the 3D model and has been exhibited around the world. One day it will be installed in Palmyra.

“The arch was never 3D scanned,” says Dr Alexy Karenowska, director of technology at Oxford University’s Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA). “We created 3D models using photos from all kinds of sources, including from tourists. It would have been possible to use Lidar or any surface-scanning tech to create a 3D model, but we didn’t have that luxury because it had already been reduced to rubble.”

Using photographs to create detailed 3D maps and architectural drawings is called photogrammetry, a technique that is becoming increasingly important in surveying cultural treasures. The IDA has even created the Million Image Database, a kind of Wikipedia or Google Earth for threatened heritage sites, to which anyone can upload photographs.

For now the database has a slight bias towards sites in the Middle East, but there’s a reason for that. “It focuses on endangered archaeology, and right now that’s where a lot of it is,” says Karenowska, adding there is also enormous enthusiasm for digital preservation in that region.

Determining what technology to use to map a site, and how long it will take, depends on scale and location. Drones, for example, are useful for inaccessible hilltop sites such as Machu Picchu in Peru; for sprawling sites like Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the biggest issue is lack of time.

“It’s essentially a big data-gathering problem, but it’s not rocket science,” Karenowska says. “It’s about organised data gathering and good data storage.”

While VR is being used in Dunhuang to reduce the need for tourists to go inside the caves, Karenowska thinks that a mobile augmented reality (AR) experience is really what 3D imaging should be aiming at. “We can now produce a projection of what a structure might have looked like, then superimpose it onto the natural environment through AR goggles,” she says.

As AR creation software becomes more streamlined, expect such projections – via AR glasses but also on phones – to become as common at historical sites and museums as audio guides are now.

Back in Dunhuang, they explicitly don’t want tourists wandering about using AR, Pokemon Go-style, but they do plan to make the site’s 3D cinema experience even more immersive. “We will keep applying the most cutting-edge technology, including 4K or even 8K, whenever needed in cave study, public education and opening to visitors,” Ding says.

UNESCO in war against Islamic State to protect world’s cultural heritage from destruction

Bird praises the Dunhuang Research Academy’s work so far, but fears for its long-term future. “The site is remote enough, and insulated enough to be enjoyed,” he says. “But the crowds that Venice – at the other end of the Silk Road – sees each year would surely sink Dunhuang.”