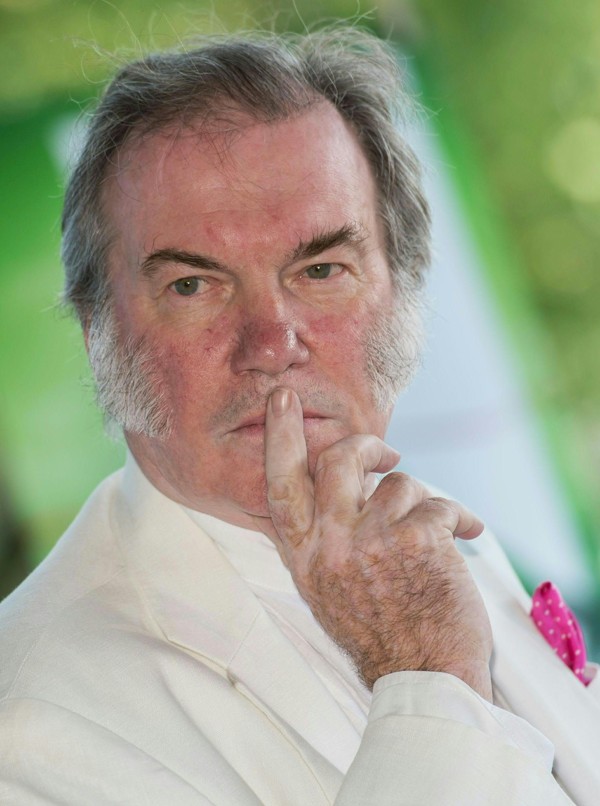

When Welsh National Opera director fell in love with music, and how he depicts mad love triangle of Pelléas et Mélisande

Captivated as a five-year-old by a lone voice singing in a darkened barn, David Pountney has made a career of directing opera singers. He explains how he uses water as a metaphor for a character’s shifting mental state in Debussy’s opera

He was five years old, crouched in the crook of a beam in an old barn in southern England. And then a man began to sing in the gloom. The boy never forgot it. And it changed his life.

“It was 1952, I was five, it was the coronation year, and since the war my parents had been going for the holidays to an institution called Music Camp on a farm in Berkshire [a county in southern England],” recalls David Pountney, one of Britain’s leading opera directors.

“It was Florestan’s aria Gott! Welch Dunkel hier! [“Oh God, what darkness is here!” from Beethoven’s Fidelio]. And the thing that stuck in my mind, which is probably odd for a five-year-old, was this one lone man singing about the darkness. Of course, I had no idea what he was singing about, but evidently his plight made an impression on me.”

The other thing he never forgot from that holiday, he said, was seeing the musicians digging the orchestra pit, “which I think is something that needs to be repeated for every orchestral union member … first dig your own pit”, Pountney says jokingly.

Who says opera’s boring? Hong Kong music enthusiast aims to stage classics with a fun and modern twist

He is in Hong Kong this month with Welsh National Opera, which is performing his production of Claude Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande at the Hong Kong Arts Festival.

“Another early musical experience is listening to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony on the radio with my mother in front of the fire when I was six or seven and saying afterwards that I wanted to learn how to play the trumpet, which I then did,” says Pountney.

He did it rather well, played for the National Youth Orchestra, and when he went to the University of Cambridge – where he had been a boy chorister as well – he continued to surround himself with music – singing, conducting and opera.

Although in the beginning he rather fancied conducting, he quickly realised that, compared to his best friend at Cambridge, he wasn’t as good as he could be at it.

“I could see that, in terms of being a conductor, he had more musical talent than I did. I thought I shouldn’t do that, as there was already someone better than me … so I thought I’d better do this [opera] directing thing instead because I seemed to have more of a talent.”

It only became evident later that he had set his sights very high. The friend was Mark Elder, now Sir Mark Elder, knighted in 2008 for his services to music as artistic director of Manchester’s Halle Orchestra.

Pountney directed nine operas at Cambridge, and in the intervening years he has directed dozens more, for English National Opera, Scottish Opera, Opera Australia, the Vienna State Opera and, since 2011, as artistic director of the Welsh National Opera based in Cardiff.

It’s like one of those delicate Japanese constructs in which the sum of a person’s sadness is summarised in the falling of a leaf into a pond – that’s the way Pelléas works

Pelléas et Mélisande is unlikely to be criticised for being overburdened by reality. It is based on a play by symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck, about a man who comes across a young woman, Mélisande, who seems to have lost her way.

He is smitten with the woman. He takes her home as his bride, but his half-brother Pelléas also becomes fascinated by her. All sorts of misunderstandings arise; needless to say, the triangle does not end well.

Pountney conceived the piece as a follow-up to his 2013 production of Alban Berg’s opera Lulu, hailed by critics variously as dazzling, unsparing and imaginative.

“I realised that the characters of Lulu and Mélisande were closely related in a way. They are both people without social background – they are found in some way: Lulu allegedly selling flowers outside the Alhambra cafe and nobody is sure who her father is.

“And likewise, Mélisande is found by a pond and she may or may not have been married to the man who owned a crown lying in the water but that’s all we find out about her …. So this person without background is imported into some kind of family situation and causes mayhem and destruction.”

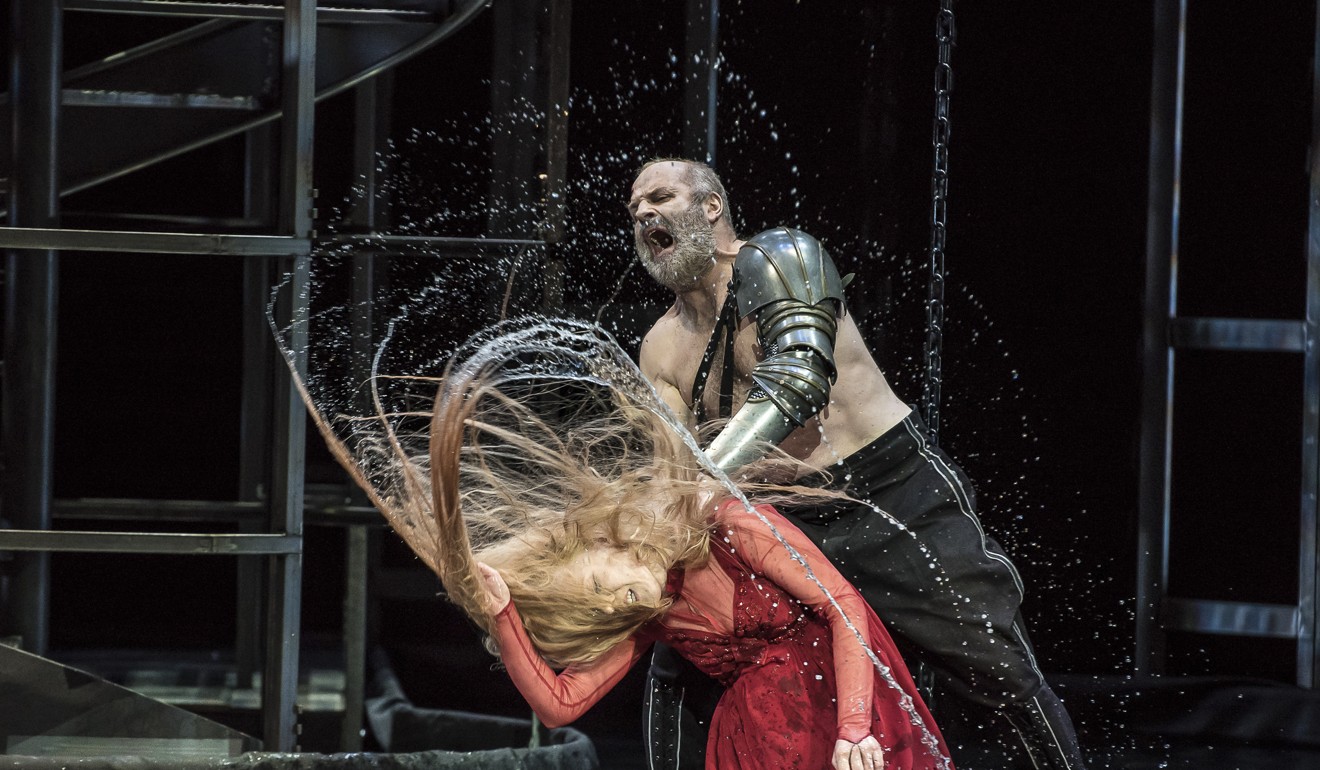

Both productions have a barbed wire circular staircase and cage structures in the set, deriving from the idea of a zoo.

Life of a domestic helper dramatised in chamber opera for Asia Society by Hong Kong playwright

“The significant element we added for Pelléas is that we flooded the inside of the menagerie so there is water: she is found by a pool … the crown is in there … and water became a powerful metaphor for her shifting mental state … under the influence of Mélisande.”

Pountney says: “When people think of opera they tend to think of very in-your-face, grandstanding, loud, rambunctious music and drama.” But Pelléas et Mélisande is the opposite.

“It’s like one of those delicate Japanese constructs in which the sum of a person’s sadness is summarised in the falling of a leaf into a pond – that’s the way Pelléas works,” the opera director says.

“If they’re waiting for the big tune or the big chorus or the blazing trumpets or the march from Aida they’re not going to get it. But it is exquisite, and it’s important to say to the audience they need to come and relax. And let it work its magic.”

Pelléas et Mélisande, Welsh National Opera, Grand Theatre, Hong Kong Cultural Centre, March 15 and 17, 7.30pm, HK$360 to HK$1,020. Inquiries: 2824 2430