Advertisement

Book review: Sheriff of Wan Chai – author fluffs his best lines

Disappointing memoir about a Hong Kong life more observed than lived from former senior civil servant and policeman, who makes little effort to engage his audience

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Sheriff of Wan Chai

by Peter Mann

Advertisement

Blacksmith Books

2 stars

Advertisement

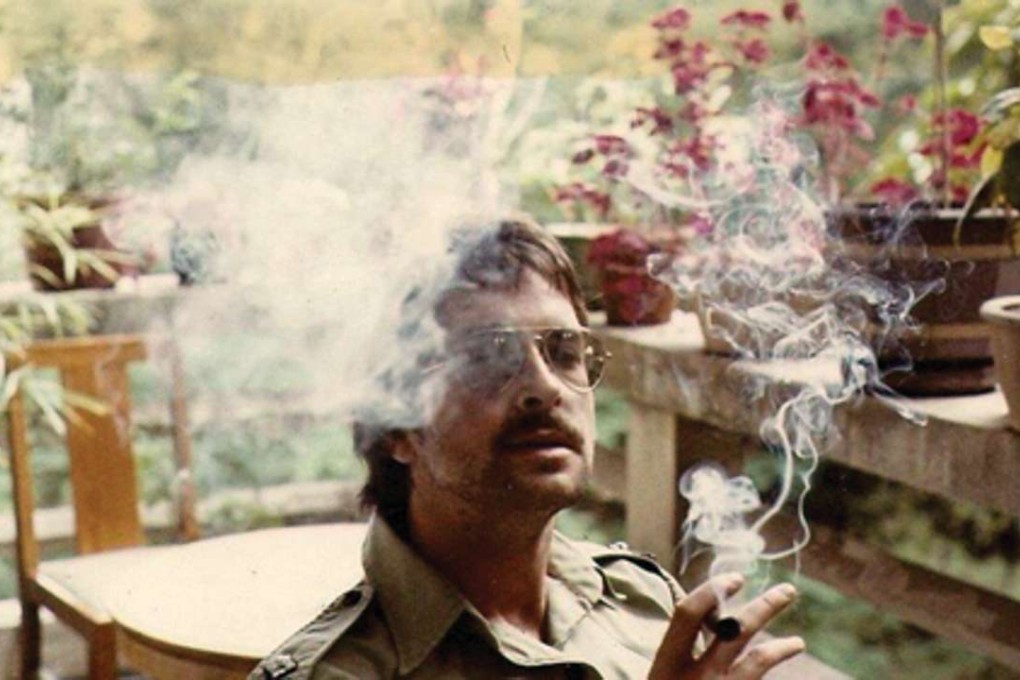

Peter Mann’s memoir, Sheriff of Wan Chai, is more than a police story. The author is portrayed on the cover in a Royal Hong Kong Police (RHKP) uniform, yet the 242-page book devotes only 33 early pages to the Englishman’s two-and-a-bit years on the force. The rest of this biography is largely a bland, need-to-know timeline of Mann’s subsequent 22 years in the Hong Kong Civil Service; his Garrison Players performances; and where he went for his holidays.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x