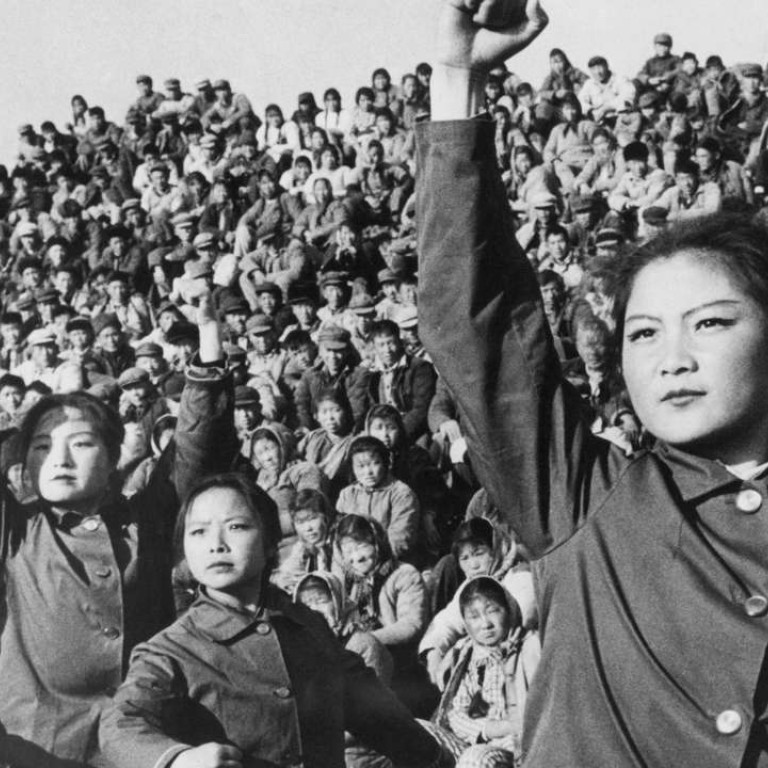

Book review: The Killing Wind is not for the faint-hearted as it charts Cultural Revolution horrors

By depicting the murderous upheaval unleashed in one cluster of villages in Hunan, author Tan Hecheng brings out the senselessness of what Mao Zedong unleashed – and offers remarkable testament to Chinese historians’ work

But for a couple of weeks, from around August 20, the marketplaces, and the areas by the rivers and fields, are the scenes of a new kind of activity – the brutal slaughter by neighbours, relatives and friends of people from within their communities. The spate of daylight murder ends as abruptly as it had begun.

It is hard to exaggerate the force of Chinese journalist Tan Hecheng’s The Killing Wind. Tan, eerily, had visited the township of Daoxian – the focus of his study – only a few weeks after the murders had happened. As a young “sent down youth” then, in the early period of the Cultural Revolution, he had come to this area with a friend.

Of course, he was not aware of the events that had just happened. His description of the unsettling silence of the place he looked through, a place that he was to study so deeply decades later, is highly symbolic.

National leaders such as Hua Guofeng, then a province-level party boss in Hunan, were to demand that it was best just to let the murders fade from memory.

Tan’s book lets the brutality and senselessness of this case of auto-genocide scream from the page. This is not a book for the faint-hearted.

This is particularly the case because of the very understated mode of presentation. Tan sets out the localities, the numbers involved, the dates, specific times, and the ways in which people were executed, with meticulous precision. He doesn’t embellish or dramatise. He simply states how some of the victims met their end. But that gives this work even greater weight and authority.

One of the characteristics of a lot of scholarship on the Cultural Revolution, the epic mass movement that swept China from 1966 for a decade until Mao Zedong’s death, is that it either puts too much emphasis on politics, or elite power struggles, or simply presents a catalogue of misdeeds in which culprits are anonymous. There is little attempt to address the question of agency – of why people did what they did, and what it actually meant within communities that were affected.

These criticisms cannot be made of this book. It is scrupulous in naming the perpetrators, and even in trying to track them down decades later and find out how they now understand their actions back in 1967.

What is clear, after reading through Tan’s testimony, is the complexity of the movement – the ways in which some figures were simply manipulating the opportunity of the Cultural Revolution to fulfil vendettas against their neighbours or relatives. Others truly did believe the narrative of cleansing class struggle at the time. As with Nazi Germany, ideas of horrifying simplicity took a hold on society, and led to actions of inhuman brutality.

The chapter on the treatment of women is particularly hard to contemplate, both in the gang rapes that happened, the utterly barbaric ways in which some were executed and the incomprehensible ways in which some of the women survivors were forced to marry those who had slaughtered their husbands and children.

It would be hard to recommend this book more. In taking the Cultural Revolution, with all its strangeness and immensity, down to the level of a particular community, with named figures and the real actions they were involved with, it makes the history of this era look very different.

This is finally a truly remarkable testament to the ways in which Chinese historians, working within China, have been able, despite all the restrictions and restraints there, to write some of the most amazing, powerful material.

The Asian Review of Books