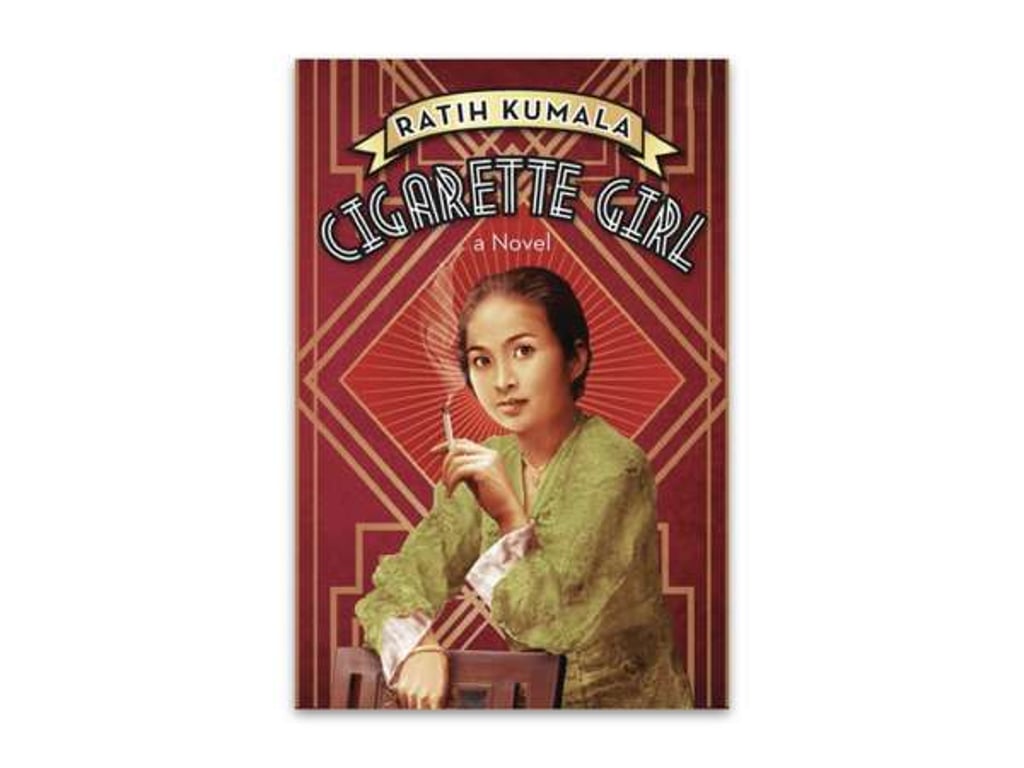

Review: Cigarette Girl – love, cloves and enmity in post-war Indonesia

The story of two Javanese cigarette-making families is also one of secrets and discoveries, and for readers beyond Indonesia it offers fascinating glimpses of the country’s recent history and its people’s ways

by Ratih Kumala (translated by Annie Tucker )

Monsoon Books

3.5 stars

Redolent of the ubiquitous aromatic kretek cigarettes, this book by Indonesian writer Ratih Kumala follows three generations of two Javanese families from the time of the Dutch surrender to the Japanese in 1942, via the crackdown on the communists and the massacres of 1965, to the present.

Cigarette Girl has been fluently translated by Annie Tucker, who made the sensible decision to leave many terms in either Bahasa Indonesia or Javanese – most, although not all, with explanations in the text, adding a layer of linguistic richness and interest to an already interesting and absorbing novel.