Book review: pictures of Delhi’s LGBT community offer rare glimpse into hidden lives

Delhi: Communities of Belonging reveals a vibrant community whose members navigate archaic laws and modern technology to find each other

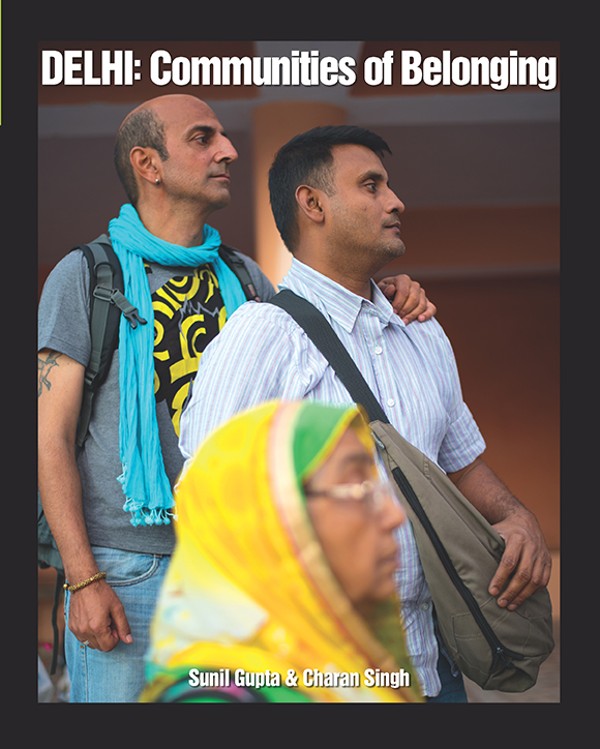

Delhi: Communities of Belonging

by Sunil Gupta and Charan Singh

The New Press

4/5 stars

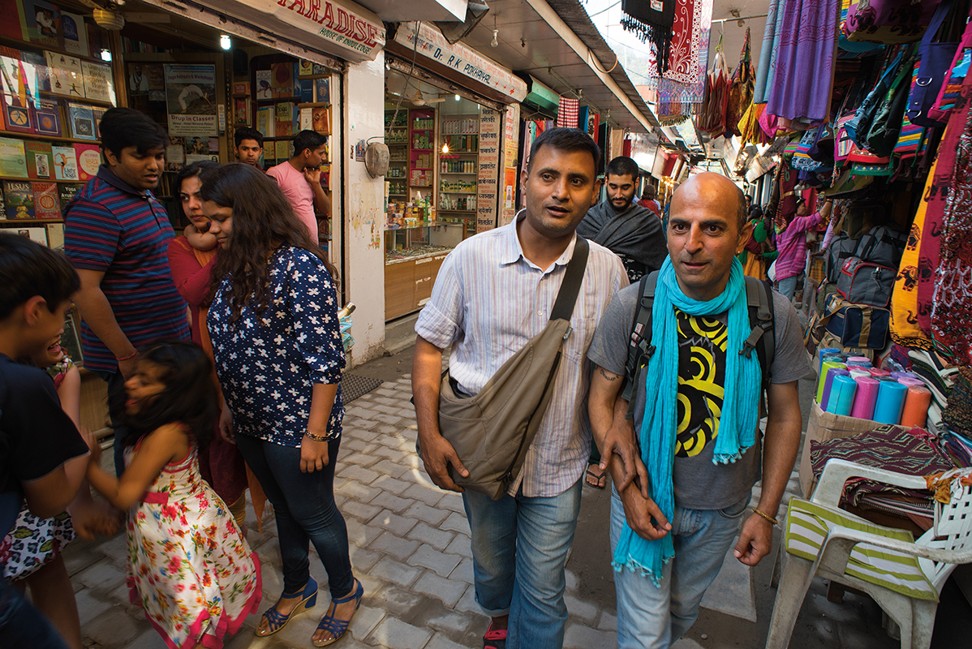

Indian photographers Sunil Gupta and Charan Singh have provided a rare glimpse into the lives of LGBT people in India’s capital city in their new photo book, Delhi: Communities of Belonging.

One of the subjects of the book is Sanal, who grew up in a middle-class family in Delhi wanting only to dress up and dance. Now in his twenties and working as an urban researcher, he says it’s easy to meet partners on the internet, but feels it’s dangerous to go to gay events. “What if they are raided?” he worries.

The city’s queer population operates furtively, but the internet has changed the way LGBT people interact with each other. Cruising spaces are being abandoned for the convenience and safety of private places as the mobile-savvy younger generation finds ways to navigate the legalities of being queer in India.

Gupta and Singh follow some queer people from the lower strata who still use cruising spaces to meet men. “I come here to Connaught Place to seek out sexual partners on my way home [from work]. I don’t want to disclose my identity in my neighbourhood, which is a bit unsafe and rough,” says Jatin, another subject.

India has a vibrant gay community, but its members must navigate archaic colonial laws that outlaw homosexuality. In the introduction to the book, Indian gay studies scholar Saleem Kidwai notes that homosexuality was accepted in Mughal times, but “Victorian Christian values” were imposed during colonial rule that made homosexuality a taboo in the 1800s.

India’s anti-sodomy act was passed in 1861 and punishes any act of “carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman, or animal” with a jail term from 10 years to life. Historically this has led to only a handful of convictions, but it has been used to harass and blackmail homosexual men.

Since the Supreme Court refused to repeal the act in 2013, there has been a spike in arrests of queer men. In 2015, more than 1,400 arrests were made under the act, says a National Crime Records Bureau report.

At the same time, there has been a slow emergence of queer activism in Delhi. “A visible queer community has emerged in Delhi over the past two decades. What was silent and private has emerged into the public sphere. Gupta’s and Singh’s work bears testimony to this,” educator Gautam Bhan writes in the opening of the book.

India’s rigid social structure forces many gay men to get married to women, pushing them further into the closet. As a result, many battle with dual identities – while trying to maintain a relationship with their wives and sometimes children, they also meet men for sexual pleasure.

Jatin and Kishan (only the subjects’ first names are used) are married but continue to meet men for pleasure. And the biracial lesbian couple Geeta and Kath talk about how they “only felt comfortable coming out in the United States”, where they also have a home.

In such an environment, life for queer people in India can become stifling, and the book subtly emphasises the importance of building networks, often capturing the subjects with their friends and families.