Booming book sales in India a sign of the good times

Strong economy, rising literacy and some prize-winning authors are propelling the country’s publishing sector, and one way to ensure a non-fiction best-seller is to include India in the title, say experts

Controversial politicians. Celebrity cricket players. Spiritual gurus. India’s publishing industry, like the country’s broader economic story, has a lot to work with.

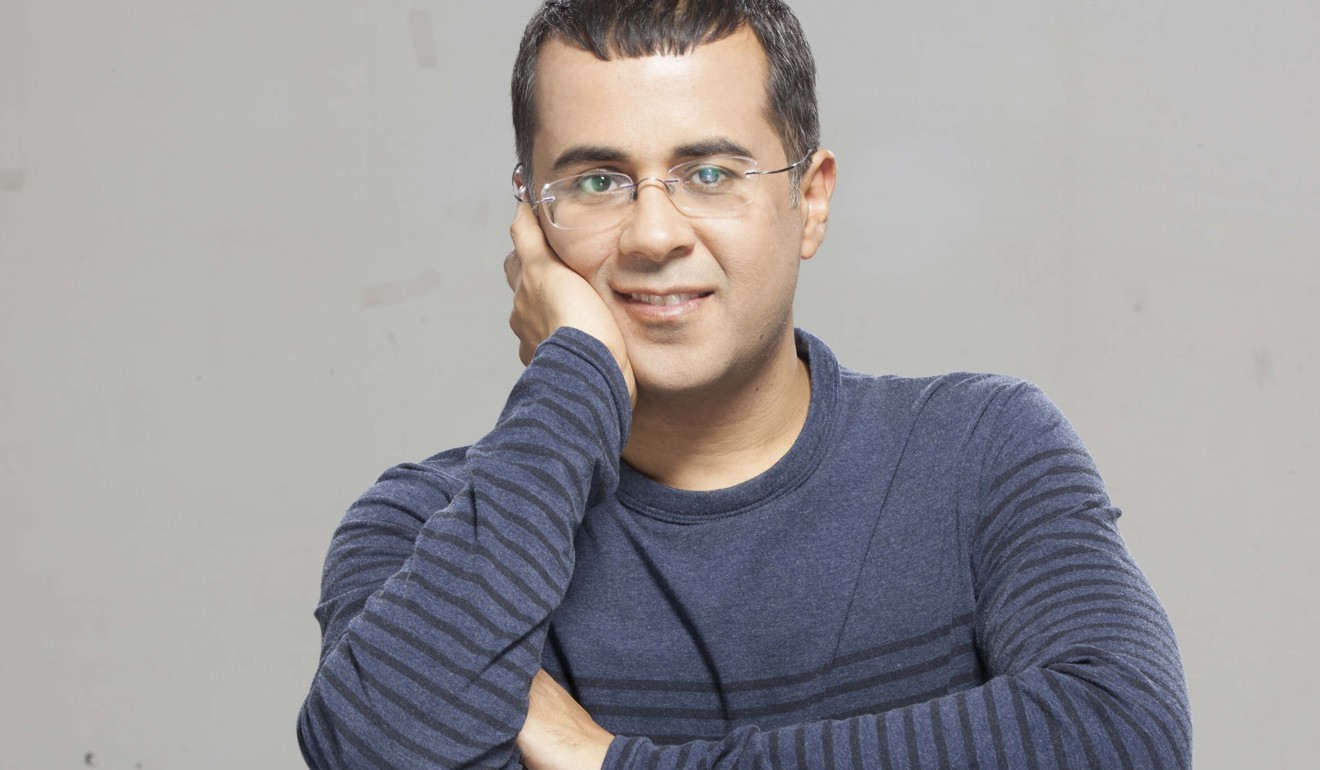

So it’s perhaps no surprise India’s GDP growth of 7.1 per cent – the fastest among major economies – is fueling a boom in book sales. Indian publishing successes, in return, can help provide insights into the country’s growth and consumer confidence. It is a land where the travails of a saucy, soon-to-be-married Goldman Sachs Group Inc banker – in Chetan Bhagat’s fictional One Indian Girl – is a runaway best-seller.

Nielsen estimates the sector is now worth US$6.76 billion (HK$52.64 billion). Led by educational books, the sector is set to grow at an average compound annual growth rate of 19.3 per cent until 2020.

India has more than 9,000 publishers to serve its nearly 1.3 billion people, but also imports a lot of books – and incoming shipments have been growing. There’s so much growth to go around that even newspapers are doing well.

“Economically, we’re in a good place,” says Ananth Padmanabhan, CEO of HarperCollins India. “This all means that there will be disposable income. Children have access to schools. Parents have access to good shopping.”

To some extent, publishing success overlays the country’s stronger regional economies. Padmanabhan says about 65 per cent of English-languages sales come from the richer, industrialised western and southern states: Maharashtra, which includes the financial capital of Mumbai, and Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala in the south.

And most revenues come from English-language sales. “It’s the aspirational language,” Padmanabhan says, adding there’s also a strong market for licensing popular English books in regional languages.

Strong sales also reflect the confidence and aspirations of India’s middle class, says Vikrant Mathur, Nielsen’s director of books for India and the Asia-Pacific. India topped Nielsen’s consumer confidence index in February, ahead of the Philippines and the United States.

“Economic growth plays a very vital role” in publishing sector growth, he says. The confidence spills over into higher-priced business and political books. “We’re obsessed with ourselves,” Padmanabhan says. “Any non-fiction with the word India in the title becomes a best-seller.”

But there are also a number of other reasons. The rise of Indian e-commerce companies has increased distribution channels. Literacy is on the rise. And the government has tried to lower school dropout rates.

Of course, it wouldn’t be India without a regulatory surprise. India’s Central Board of Secondary Education, after parent complaints about expensive privately published textbooks, ordered schools to sell only government-published books – a move that could dent booming textbook sales. Padmanabhan says it’s a “populist move” that doesn’t take quality into consideration. The government has remained firm, reminding schools recently not to engage in “commercial activities”.

Either way, the sector is still growing. One industry group, noting the dearth of data, suggests the sector could even be expanding at a compound annual growth rate of 30 per cent.