Review | Book review: Dragon Teeth – Crichton’s tale of fossil feuds has bite, but dead dinos aren’t as fun as live ones

Based on the real-life rivalry between two 19th century palaeontologists, Dragon Teeth is slow to start but eventually becomes a real page-turner overflowing with secrecy, suspicion and cutthroat competition

by Michael Crichton

Harper

3/5 stars

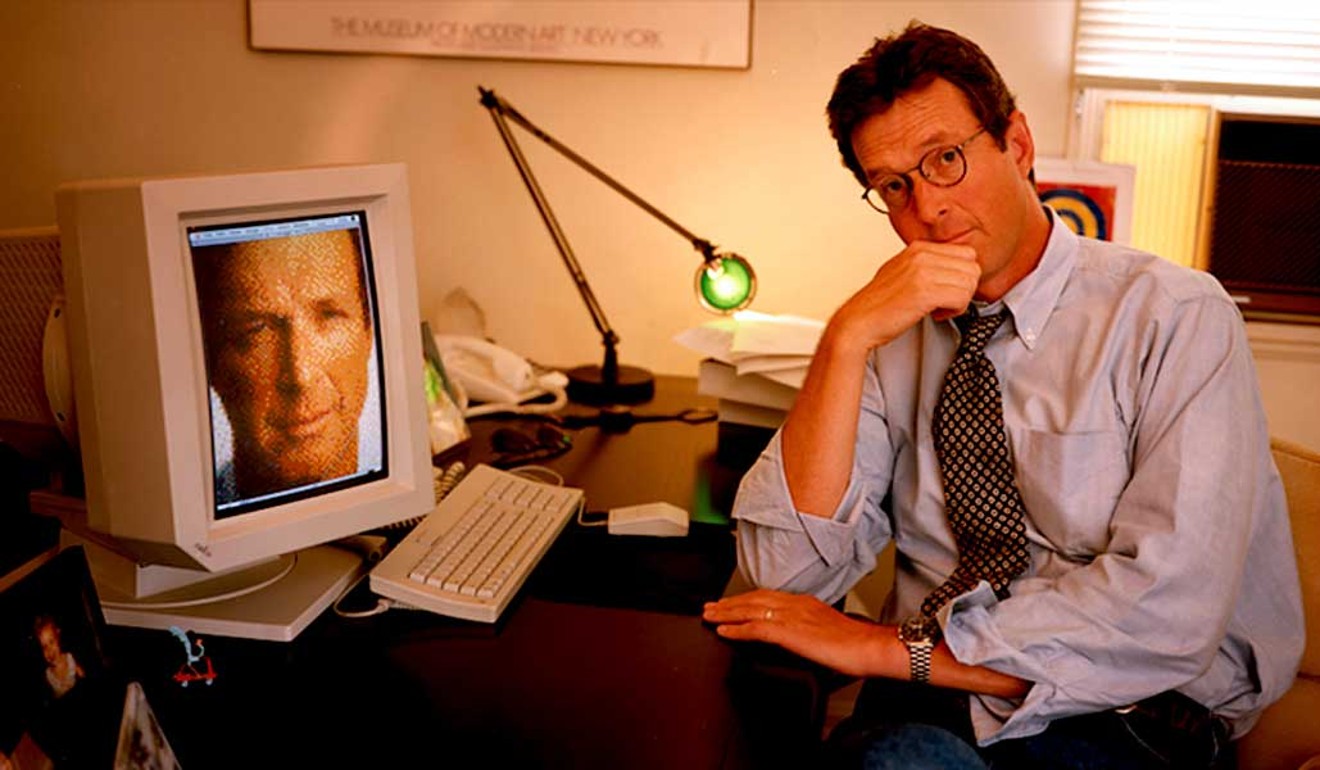

No need to Google this. Yes, Jurassic Park author Michael Crichton died in 2008 but he has a new novel, Dragon Teeth, thanks to his archives and dedicated wife, Sherri Crichton.

In an afterword, she says the book has “Michael’s voice, and his love of history, research and science all dynamically woven into this epic tale”.

The cover looks remarkably similar to Jurassic Park and, like that 1990 thriller, deals in dinosaurs. But it’s about the fevered search for fossils, not a theme park where the once-extinct predators delight and then devour visitors.

Any new Crichton novel is a cause for celebration (his books have sold more than 200 million copies worldwide), but Dragon Teeth is a slow starter.

The first half of the nearly 300-page novel feels as if you’re climbing a steep hill on an old wooden roller coaster. You’re waiting for the clickety-clack to give way to adrenaline and airtime. That moment arrives, but it requires patience.

Crichton, inspired by his correspondence with a museum curator, rooted this story in the real-life rivalry between Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. The pioneering palaeontologists were responsible for the discovery and naming of 130 kinds of dinosaurs.

Our guide to their world is the fictional William Johnson, a privileged Yale student. To save face and win a wager, Johnson finagles his way onto a Marsh fossil-hunting expedition headed west in the summer of 1876, but eventually finds himself in Cope’s camp bound for the same territories.

The Compleat Angler is a wealth of harmless mirth and useful information

This is a period when dinosaur hunting has shifted from Europe to North America, the transcontinental railroad has made the transport of mammoth bones possible, and Marsh and Cope are making scientific history. “And they knew that fame and honour would accrue to the man who discovered and described the largest number,” the book says.

It’s a historically rich time of Wild West tales and a fossil feud fuelled by science, secrecy, suspicion and cutthroat competition. The reptile riches are unimaginable, as when what will be christened a Brontosaurus is found in the Montana badlands.

“Cope measured the teeth with his steel calipers, scratched some calculations on his sketch pad, and shook his head. ‘It doesn’t seem possible,’ he said, and measured again. And then he stood looking across the expanses of rock, as if expecting to see the giant dinosaur appear before him, shaking the ground with each step.”

Johnson must figure out a way to stay alive and afloat – and safeguard the fossils in his possession – in places with no lawmen or laws. It’s at that point that Dragon Teeth picks up the pace and resembles the page-turner we expect.

This is not the first posthumous publication of a Crichton book. Pirate Latitudes arrived in 2009, and Micro, completed by Richard Preston, in 2011.

Dragon Teeth bears only Crichton’s name, but it seems as if it could have used one more rewrite or attempt to shape the material by streamlining the start and giving the front half the same sense of energy and urgency as the second.

Crichton acknowledged that he compressed the legendary Marsh-Cope antagonism into a single summer and invented Johnson. He cautions in an author’s note: “I would not read this novel as history. For history, read Charles Sternberg’s detailed account of Cope’s trip to the Montana badlands in The Life of a Fossil Hunter.”

Colm Tóibín explores the war at home in his reimagining of the myth of Agamemnon

There could be no Jurassic Park without these bone wars, but live dinos trump dead ones any day. Still, if early National Geographic Channel plans to turn Dragon Teeth into a limited series come to fruition, Marsh and Cope could become rock stars in the literal sense of that phrase.

As Dragon Teeth reminds us, the gold rush had nothing on them.