Ovidia Yu, gay feminist author from Singapore, takes a cosy-but-candid approach to addressing the Lion City’s ills

With two new crime novels out this summer that mesh their mysteries with subtle social commentary, Yu is showing that you don’t have to be angry and aggressive to make political points

Ovidia Yu’s straight take on her countrymen is characteristic of the way she sees a lot of things in Singapore, from the exploitation of migrant workers to the state of women’s rights.

“Singaporeans are very pragmatic, I think. We do what we can to survive. If there’s no point making a fuss, we don’t – until there is something to be gained.”

Book review: Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows – Singaporean author’s novel blends romantic comedy with family saga

Her refusal to shy away from controversial issues has seen Yu, 56, become one of Singapore’s most acclaimed, eclectic and internationally successful modern writers. But it all could have worked out very differently had she pursued a career as a doctor after earning a rare medical scholarship offered to women by the Singaporean government.

“Being Singaporean and kiasu [rough translation: competitive and ambitious], you apply for the hardest thing,” she says. “That was medicine.”

But she decided to drop out and pursue her dream of being a writer – a decision so controversial it prompted Singapore’s prime minister to make an angry telephone call to her father.

Yu, however, went on to attract early attention with a prize-winning short story, A Dream of China, before concentrating on writing for the theatre. She produced two unsettling, confessional but extremely funny satires about misogyny (The Woman in a Tree on a Hill) and body dysmorphia (Breastissues). These works earned her a reputation, according to academic and theatre director K.K. Seet, as “Singapore’s first truly feminist writer and unabashed chronicler of all things female”.

Given Seet’s assessment, Yu’s subsequent transition into the world of crime fiction might seem somewhat unexpected. This is even more so given her first books within the genre, starring Aunty Lee – a wealthy, open-minded cook-turned-amateur-sleuth – have been filed under the gentle genre of “cosy mysteries” (think cake, charm and crime, in roughly that order).

Review: Once We Were There – debut novel breaks every taboo in the book for Malaysians

Nevertheless, this summer alone, Yu has published two crime novels from different series. Meddling and Murder is the latest Aunty Lee investigation. The disappearance of Aunty’s Filipino maid, Nina Balignasay, prompts a characteristically quirky plot, and some pointed commentary about divides in race, religion and class. “Nina suspected Aunty Lee was barely aware how differently the island’s rules and regulations looked to those below and from the outside,” Yu writes.

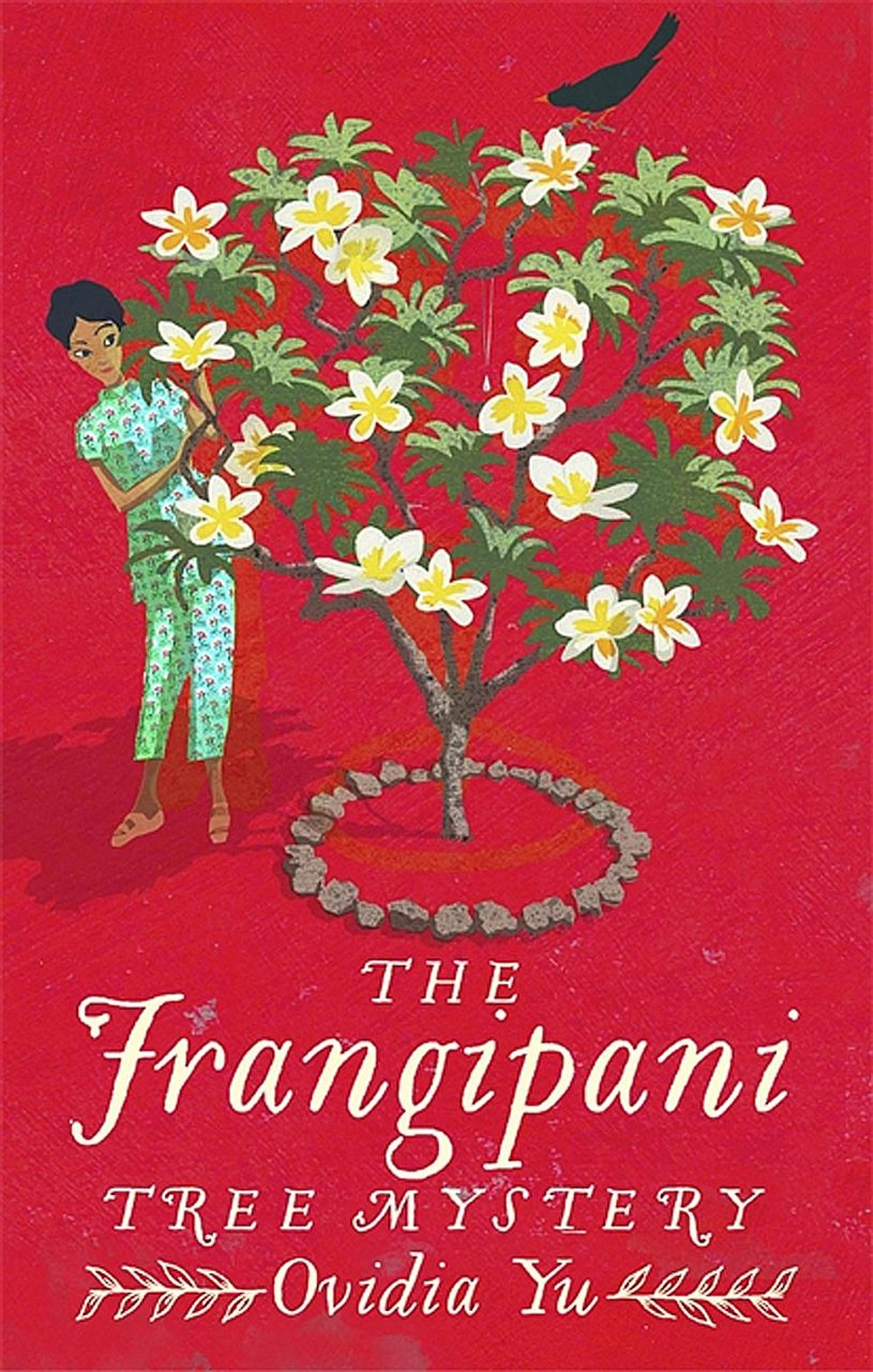

The Frangipani Tree Mystery, meanwhile, kick-starts a new series set in 1930s Singapore. Su Lin is an unassuming, but brilliantly observant young Chinese-Singaporean who is drawn into a murder mystery enveloping the bumptious colonial governor Sir Henry Palin, whose daughter’s nanny is found dead beneath the titular tree.

I am not making fun of the issues. I take them seriously. But you don’t have to be ugly to make a serious point. It’s not sugar-coating, it’s lubricating the idea so you can slide it in and say what you want

What unites the two novels are intriguing explorations of women’s lives, and of course Singapore itself. “I don’t really know about anywhere else,” Yu explains. “I thought there was nothing interesting to say about Singapore until I left. I went to America and England for a while. Just short trips. When you see how other people see Singapore you realise there might be something to write about. The fish doesn’t talk about the water.”

This last phrase sounds an almost cautionary note, given Singapore’s strict censorship laws. It does, though, also suggest a link between Yu’s radical plays and her Singaporean remixing of Agatha Christie. The attractive, superficial lightness of both incarnations conceals candid critiques about her homeland’s past and present.

A victim of censorship in the past (“Singapore is very careful about what goes on,” she says), Yu argues that her desire to entertain enables her to insinuate political critiques and risqué elements into her work.

“I am not making fun of the issues,” she says of her socially conscious plays. “I take them seriously. But you don’t have to be ugly to make a serious point. It’s not sugar-coating, it’s lubricating the idea so you can slide it in and say what you want. It goes back to not attacking people up front. They are not enemies.”

This clandestine approach to literary protest also seems a natural extension of Yu’s own personality, which is amicable, positive and unfailingly composed. When I ask about the state of women’s rights in Singapore, she replies: “Not much worse than the state of men’s rights in Singapore right now, so in a sense pretty good. When there’s no sharp contrast it doesn’t hurt so immediately.”

Yu displays similar care talking about LGBT rights in Singapore. Openly gay, Yu lives in a country that continues to criminalise sex between consenting adult males.

“Being gay in Singapore has influenced how I see the world. [But] I don’t consider myself a ‘gay writer’ any more than I would categorise myself a ‘female writer’ or ‘cosy writer’. I am a writer and I write about the world as it appears to me the best I can.”

Singaporean writer Ovidia Yu debuts two appealing new sleuths in The Frangipani Tree Mystery

She highlights the social and legal discrimination towards Singapore’s transsexual community. “I remember a friend’s joy when she finally managed to make down payment on a scooter because that meant she could work as a dispatch rider and give up sex work.”

The focus of Yu’s works on economic disparity, however, and her portrayal of Singapore’s exploitation of migrant workers through characters such as Nina in Meddling and Murder, identifies the main cause of her political anger.

“The state of migrant workers and foreign domestic workers [in Singapore] is definitely not good. Many get conned into paying huge amounts to contractors in their own countries. When they get here they find the jobs they were promised don’t exist,” she says.

“When they get sick or injured there’s no insurance. If you believe, as a feminist, that all people are entitled to equal civil rights, then [you can see] their state is far worse. I think it’s terrible that people here may see it as the norm, simply because we become inured to what is happening.”

Review: Once We Were There – debut novel breaks every taboo in the book for Malaysians

The Frangipani Tree Mystery could be read as Yu’s attempt to trace these contemporary ills to Singapore’s past under British colonial rule, which exploited native workers and migrants alike. “There was actually a huge depression going on. People were out of work – people coming from China and Russia, bizarrely enough. War was starting, even though it wasn’t openly declared. It was a terrible time, yet my grandparents looked back on it [fondly] because it was before the [Japanese] occupation.”

While the novel favours outsiders such as Su Lin and the enigmatic colonial police detective Thomas Le Froy, it refuses to heap scorn on even the most unpleasant of the British colonial rulers. “The British said we were all uneducated savages and we should all become Christian, but they built hospitals and they built roads and they tried to give people fresh water. Of course they were trying to make money for the Crown from rubber and tin. They were trying to be nice to the animals, even if they saw us as animals.”

Such equanimity has proved contentious: one reviewer in The Straits Times complained “how forgiving [Su Lin and the native Singaporeans] are of even their masters’ most dreadful trespasses”, although they conceded the characters might offer “an interesting study of internalised racism”.

Yu argues that her equanimity is motivated by her conviction that even the worst individual is a product of their culture and historical moment. “In that time, the British had to think that way so they could go on governing. As people like me rise up, you can no longer do that, so you shift the boundaries of what is right and wrong.”

Swimming in Hong Kong author Stephanie Han explains how she figured out her own story

Here in essence is Yu’s defence of her own “cosy” outlook – one that includes rather than dismisses, seeks to understand rather than alienate. For Yu, reading breeds empathy.

“If you are writing aggressive, angry pieces, people go into defensive mode and stop listening. If you read stories and see just one person from the inside, then the next time you meet someone of a different colour you’ll connect then to the character rather than your image of badness. It is suddenly less scary.”

Whether you believe such idealism or not, it’s good to know that Yu is out there fighting the good fight, and entertaining us as she goes.