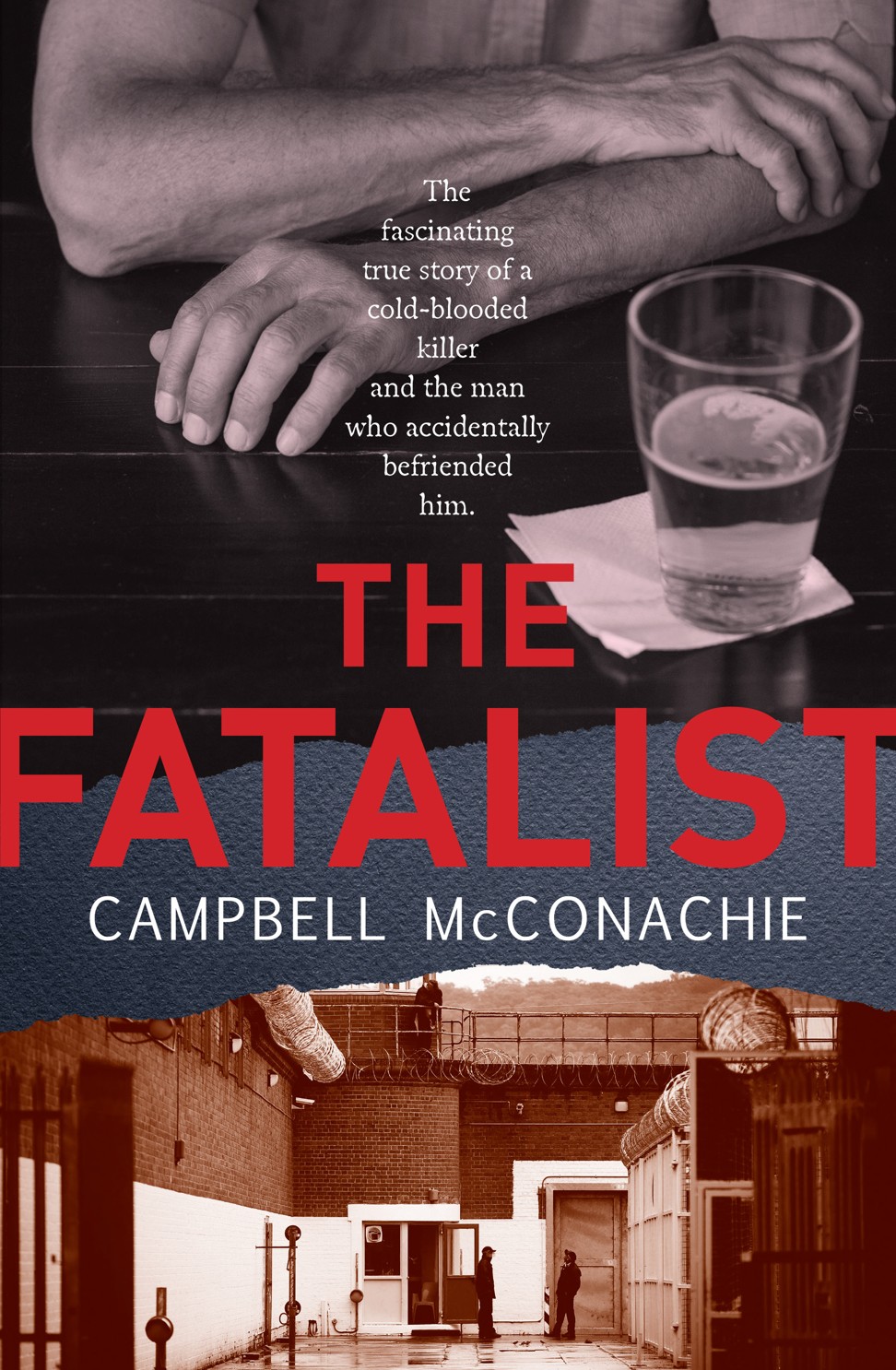

Why I wrote a book about murderer Lindsay Rose, my hitman mate from the pub: Campbell McConachie

McConachie knew little of Rose’s past before he pleaded guilty to five murders in 1998. Here, he describes the logistics and ethical quandaries of not only profiling a murderer, but giving him a microphone by printing his letters

Campbell McConachie was just a teenager when he first met Rose, six years before the double murder, at a pub in Sydney’s inner west. He only knew snippets of his drinking buddy’s various and past lives, which comprised brothel owner, drug dealer, ambulance officer, private investigator, car thief, hijacker, volunteer firefighter – and arsonist – and mercenary.

Jen Waite needs more distance from her true tale of being married to a psychopath

As McConachie recalls in his new book, The Fatalist: “When I first drank beer with Lindsay, he’d already killed three people. Oh, we had no idea. He’d walk into the front bar of the Burwood Hotel and he’d scan the room. To the eyes he met and knew he’d nod a hello, or perhaps he’d bellow it if it was late-night noisy, and if I’d looked up from the form guide or the pool table I’d look away and hope it was me he came to talk to. He was ebullient and he would give you his full attention.”

During the course of 50 visits to the High-Risk Management Correctional Centre at the Goulburn Correctional Centre – a “supermax” security prison in New South Wales – McConachie interviewed Rose about his life and crimes.

Of their first meeting there, McConachie describes a man who “zips his lips a couple of times when about to mention people or actions that could incriminate others. He’s perfectly comfortable with who he is and what he has done and he tells me a myriad of stories, often punctuated with his infectious, wheezing laugh, his chin drawn down into his throat. But some of his stories involve the misfortune of others – his victims – and I stop myself from joining him in laughter.”

The Fatalist is McConachie’s first book. Here, he describes the logistics and ethical quandaries of not only profiling a murderer, but giving him a microphone by printing his letters.

Were there doubts you had to put aside to write this book?

Yes – a concern for the victims’ surviving family members. I really can’t imagine the enduring grief from losing a loved one to violent murder. A homicide victims’ support organisation told me that most people would prefer to be left alone and not reminded of their grief. They contacted one survivor on my behalf and, quite understandably, that person declined to be interviewed.

So here I am giving Lindsay a voice – a voice he uses to set out the shortcomings of two of those victims who he believes “deserved it” – when those murdered people have none.

Halfway through the writing it struck me, as Janet Malcolm put it [in her book about ethics in reporting, The Journalist and the Murderer], that perhaps what I was doing was morally indefensible. To carry on, I convinced myself that my intentions at least were good – that some helpful insight may arise from understanding how someone can turn into a violent murderer.

What were your first impressions of Lindsay Rose, as a bloke down the pub?

He was gregarious, energetic and exuded self-confidence. I was still a teenager when I first met him so in my eyes he was like the popular boy in school.

It’s not unusual for killers to possess charm and charisma. What research did you do to prepare yourself?

I did a lot of reading on criminal psychology and psychopathy, including Robert Hare’s book Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us – and his psychopathy checklist.

I know what you mean about the charm and charisma – the other seminal work on psychopathy is called The Mask of Sanity for that very reason. The outward persona exuding confidence and charisma can be a mask hiding the damaged person behind. That’s not to say that Lindsay is necessarily a psychopath though, and in the book I explore this uncertainty a little further.

Behind the scenes of Thelma & Louise, a movie that upended Hollywood

Was it tempting to pathologise Rose?

As a layperson I was only prepared – and able – to go so far. Lindsay was a paramedic so he has some clinical foundation, and he is quite self-aware. He wrote letters to me with quite startling insights into the transformation of his attitude to the world, and I’ve included some of those letters in the book.

Did you let him read as you went along?

I sent him a few chapters to review along the way – mostly the stories about his upbringing and time in the ambulance service. There were certain logistical sensitivities with a lot of the other material – so he still hasn’t read much of the book.

[Rose] believes he was portrayed as a hitman, whereas the reality is more complicated than that. One imagines he has other motivations

He had a childhood of neglect, violence and injustice, feeling impotent, which seemed to lead to a motivation of gaining revenge and respect. Could you empathise with any of his story?

Well, that’s certainly part of his internal narrative: that he stood up to bullies, thought he was making the world a better place. I can see how he came to that world view, but I wouldn’t say I empathise with it. I’ve been careful not to editorialise – the reader is left to make up their own mind about what to feel about him.

Do you consider Rose to be a reliable narrator?

He isn’t the narrator in the book – but I know what you mean. It’s a good question because it was important to me to have that doubt – that perhaps all is not quite as he has said – so I’ve left hints in the narrative so the reader can make up their own mind what to believe.

Another Kind of Madness looks at a father’s secret illness, silence and shame

Having said that, I think he was generally truthful, but there’s that whole thing about the limitations of human memory and unconscious bias … I think we have a tendency to parse our memories through our established self-narratives rather than the other way around.

Why do you think he let you write this story?

His stated reason is: “The cops, the judiciary and the media all got it wrong. I thought if anyone could tell it right it would be you.” Part of the context here is that he believes he was portrayed as a hitman, whereas the reality is more complicated than that. One imagines he has other motivations.

How Hong Kong helped make Steve Bannon, who helped make Donald Trump

How is your relationship with him now?

We are still on good terms. I visited him recently and we discussed the pending book launch. “I’ve included your point of view,” I told him, “but I have to warn you, it does not reflect well on you.”

“Fair enough,” he shrugged. “I did kill five people.”