Review | Book review: The Chinese Typewriter – a masterstroke of linguistic history

Thomas Mullaney explores the difficulties faced throughout history in trying to represent Chinese in movable type, and what that meant for technological change and global communication

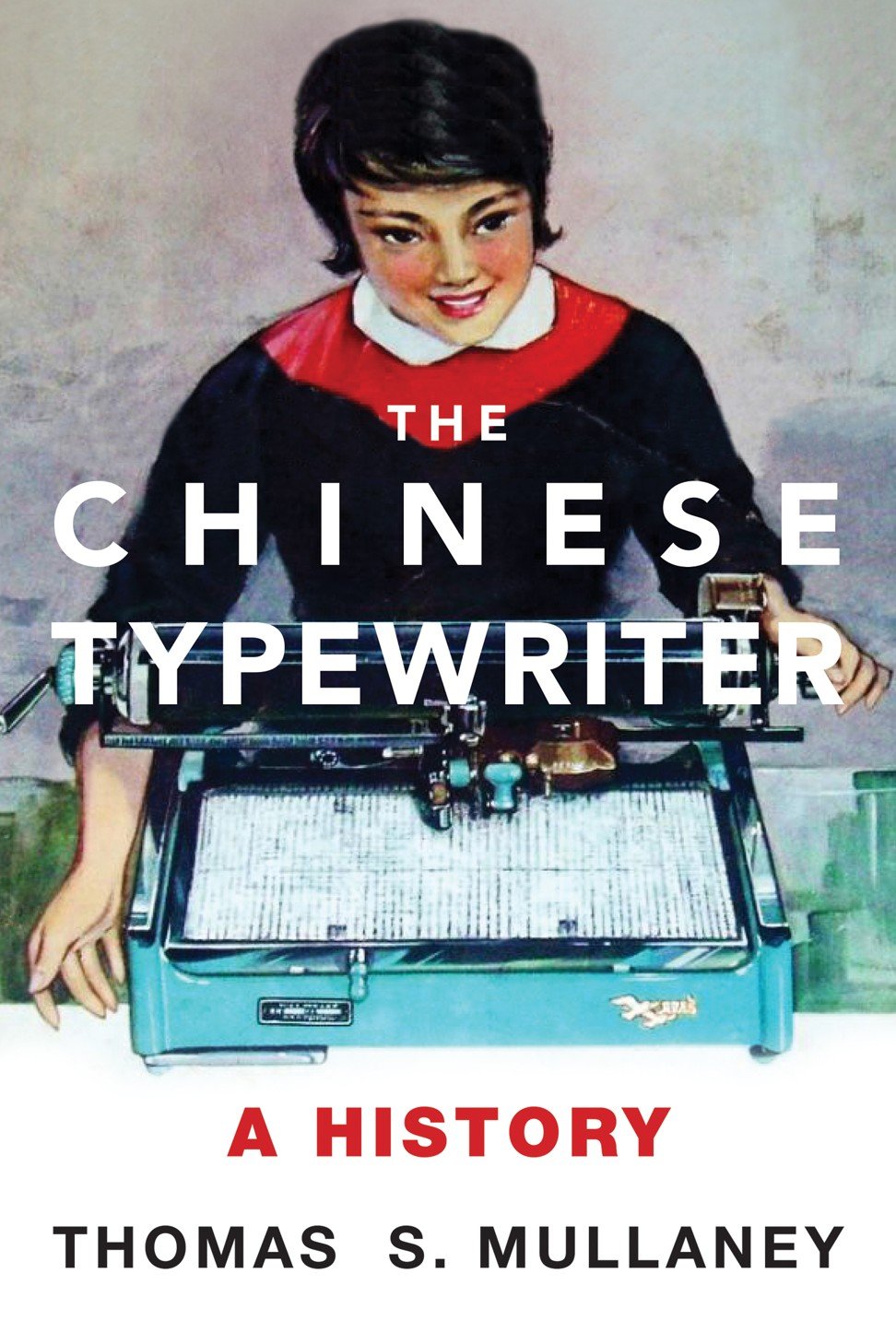

The Chinese Typewriter: A History

by Thomas Mullaney

The MIT Press

4.5 stars

Thomas Mullaney begins his captivating new book, The Chinese Typewriter: A History, by analysing – of all things – a parade. No ordinary street procession, mind you, but the parade of nations at the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

As athletes from Greece entered the Bird’s Nest stadium, they were trailed not by competitors from Afghanistan, Albania and Algeria, but by those of Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, and Turkey. The sequence, Mullaney writes, honoured the founding nation of the Olympics first, and then ushered in countries based on the number of strokes in the first and second characters of their Chinese name.

Book review: Finding Eden tells of Borneo’s beauty before deforestation destroyed the island

Never had the ceremony veered away from the English alphabetical formula. American broadcasters covering the event struggled to explain the Chinese system. Their ignorance about the written language and culture of the host nation, Mullaney infers, stretched further than the Olympic procession.

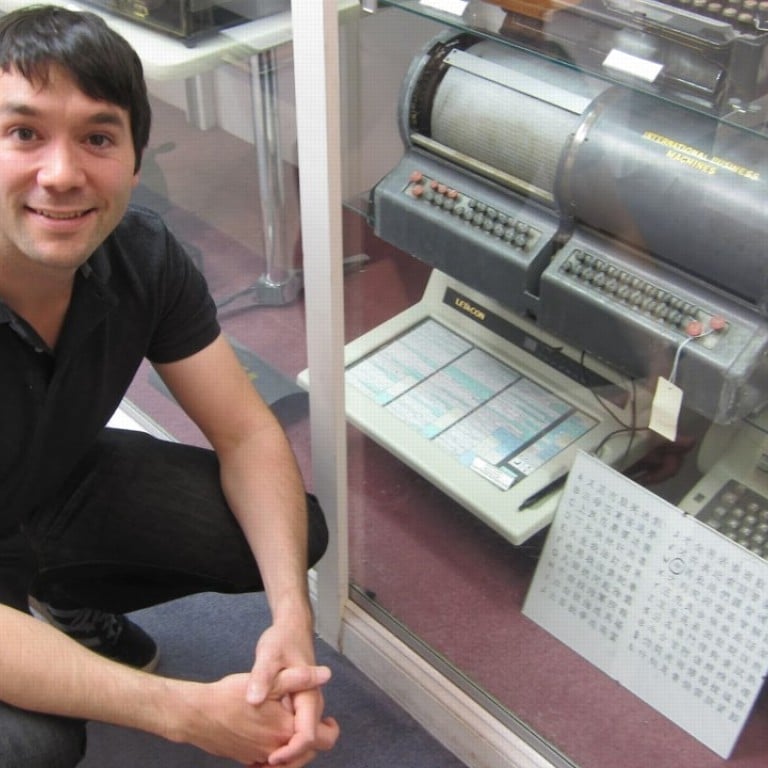

Mullaney, a professor of Chinese history at Stanford University in the United States, highlights the steep challenges posed by written Chinese, which contains more than 70,000 characters, some consisting of as many as 30 strokes. The sheer number and variety of strokes made building a Chinese typewriter appear futile.

That view held powerful sway, argues the author, quoting a comment by philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: “The very nature of Chinese writing is at the outset a great hindrance to the development of the sciences.”

However, we learn that movable type, in earthenware and wood, existed in China four centuries before Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1439. And we learn that the debates about whether a Chinese typewriter would ever be possible reflect a primitive understanding of language and of the West’s lack of knowledge about other cultures.

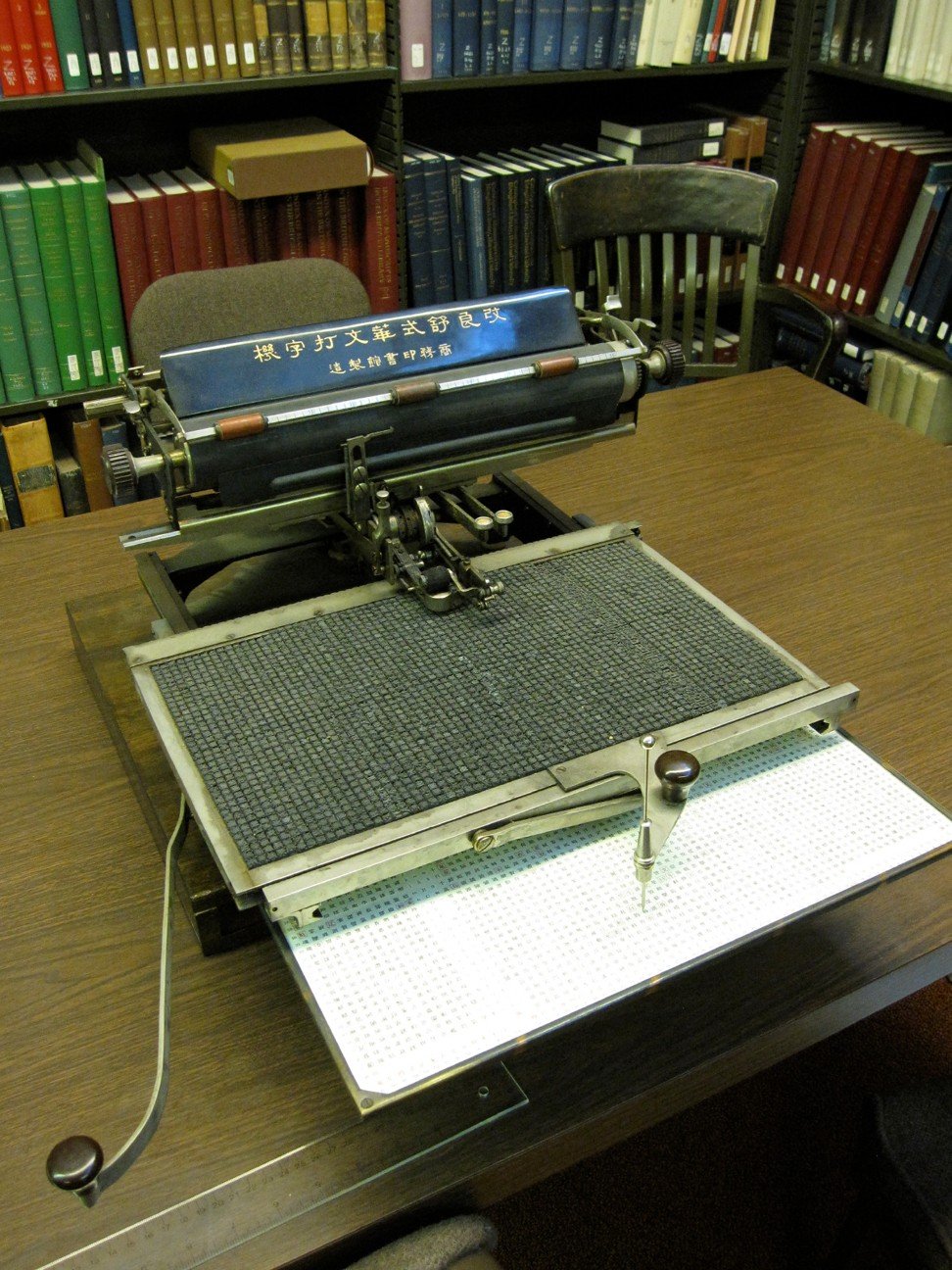

Mullaney writes that the Chinese typewriter is “a historical lens of remarkable clarity”. He explains that Chinese is one of the world’s most difficult languages to represent by movable type. The idea of arranging thousands of metal blocks – one block for every character – may have daunted many, but not all. A number of pioneering engineers, designers, linguists and entrepreneurs ventured in, all trying to buck conventional wisdom, to create a Chinese typewriter.

Review: Sweet Potato, Korean short story collection, is a gritty introduction to a little known period of East Asian history

The book introduces us to innovators such as Devello Sheffield, an American missionary, who in 1869 moved to China in a bid to devise the first Chinese typewriter. Mullaney describes his creation, in 1886, more as a system for rapidly inking characters with wooden stamps than a mechanical typewriter. Sheffield wanted a machine that could “bring with rapidity and precision from four to six thousand characters to the printing point”.

There is the engrossing tale of Zhou Houkun, a young MIT graduate who saw the slowness of typesetting as “one of the great obstacles to the advancement of general education in China”. Modernising China mattered deeply to Zhou and other well-educated expatriates of his generation. He, like Sheffield, set out to create a machine focusing on commonly used characters, reducing the total number to around 3,000.

Zhou’s typewriter came under the spotlight in 1916 when The New York Times ran a story about his prototype.

The Commercial Press in Shanghai would establish a working relationship with Zhou and the inventor earned praise, after showing at a school in his native Jiangsu province, that his machine “would print 2,000 characters each hour, rather than 3,000 per day achievable by hand”.

We also meet Shu Zhendong, who brought his movable typewriter to the Commercial Press in 1919. His contribution? A customisable product with free-floating metal slugs bearing Chinese characters that “could be removed and replaced using nothing more than a pair of tweezers”.

Mullaney shows the fledgling industry was disrupted by political upheaval. Japan, which developed a number of typewriter models in the 1930s, used its military might and war to secure its “pre-eminent place” in the Chinese market; its sales “propelled by the bureaucratic demands of empire”.

Review: Fire Road – how Vietnam war’s ‘napalm girl’ learned to stop running away and found religious salvation

The delicacy of dealing in the machine is illustrated by the plight of Yu Binqi, a Chinese swimming and table tennis champion. Yu built a company in the 1930s to rival the Commercial Press by pirating Japanese-made typewriters. But allegations that he may have secretly colluded with Japanese merchants spelled the beginning of the end of his business.

As revolution swept China in 1949, the newly formed communist government took up Japanese typewriting interests and converted them into state-owned enterprises. The domestic industry and new regime found common cause. Amid the power shifts, intriguing advances emerged.

Typists created what we would now call predictive text: they placed characters that often appeared together in written language near one another on tray beds. During Mao-era propaganda campaigns, the typists who could anticipate the political demands of the day worked the fastest.

Experimentation blossomed under communist rule in the ’50s. Mullaney describes this as a merging of three phenomena: the endorsement of mass knowledge, increasingly routinised rhetoric and unprecedented time pressure.

The book ends during the time of Mao in the ’70s and the author closes by promising his sequel will be “the first history in any language of Chinese computing”.

As Mullaney traces the evolution of the typewriter, how it came to be and what ideas won and lost, we realise he is onto something more fundamental, more thought-provoking, more enduring than a study of ingenious manufacturing.

What factors guide the mechanical expression of language? How do Chinese-language users want to search? And who is being served, and why?

The Chinese Typewriter fills a void in the records of history, yet some gaps remain. We lack, for example, a sense of the everyday use of the machines. Mullaney does not dwell, in numbers or impact, on the cultural traction of Chinese typewriters. We know only that many in government used them. However, these are minor shortcomings in a book indisputably rich in insight and detail.

Mullaney succeeds in shattering the myth that characters held China back while in turn holding a country of many dialects together; that is no small feat. What he delivers, appropriately, is a masterstroke.