Review | Book review – A Few Planes for China: The Birth of the Flying Tigers unravels the myth behind legendary fighter pilots

A John Wayne film in 1942 immortalised their exploits, and it was claimed they shot down almost 300 Japanese aircraft, but the authenticity of the Flying Tigers’ story is shrouded in doubt

A Few Planes for China: The Birth of the Flying Tigers

by Eugenie Buchan

ForeEdge

3.5/5 stars

The second world war created its fair share of myths: the “Flying Tigers” – a “small private air force that fought the Japanese over Burma and Western China”– became one of the first, providing as it did a few bright spots in the days after Pearl Harbour.

From December 1941 to June 1942, the force which “rarely had more than 40 airworthy planes” managed to take down almost 300 Japanese aircraft. A John Wayne film was released about their exploits as early as 1942.

Review: Cigarette Girl – love, cloves and enmity in post-war Indonesia

A Few Planes for China, a new book with the subtitle “The Birth of the Flying Tigers”, contains no instances of aviation derring-do; actual combat appears only in the last paragraph of the last chapter. But no matter. Eugenie Buchan has produced a well-researched and readable account of what – in retrospect at least – seems one of the more curious corners of American involvement in the second world war and one which bears some uncanny resemblances to the apparent conduct of conflicts of the present day.

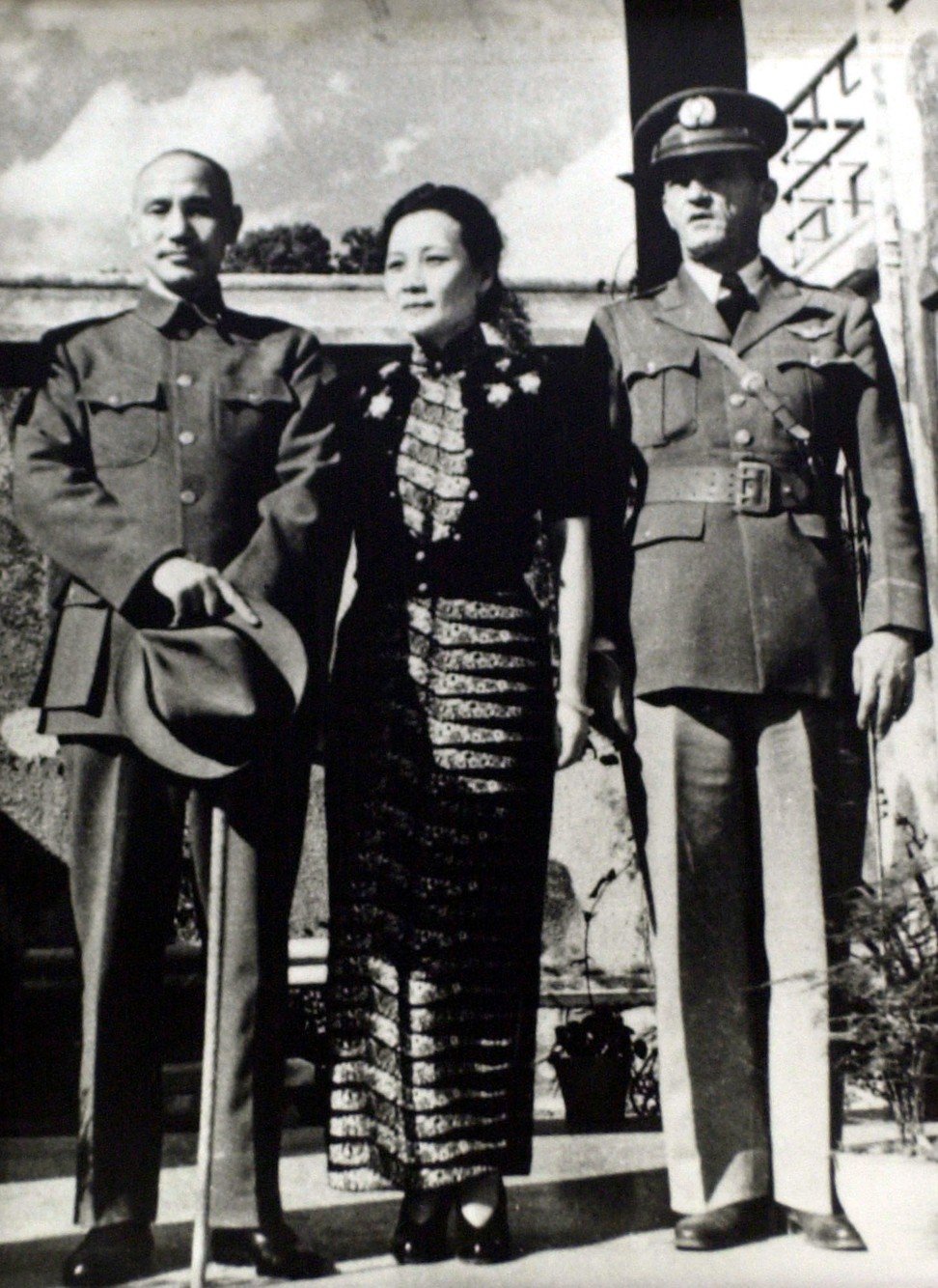

Buchan is the granddaughter of one of the protagonists: “I came across a paper bag full of old files in a wardrobe in my parents’ home in Washington, DC. They belonged to my grandfather, Captain Bruce Gardner Leighton of the US Navy. The files revealed that he played a part in organising the Flying Tigers in 1939 to 1942 while he was vice-president of a long-forgotten aviation firm called the Intercontinent Corporation.”

The conventional narrative is that the Flying Tigers were primarily the creation of its legendary commander Claire Chennault (a character based on whom was played by Wayne in the 1942 film). A 1942 book stated that “Chennault created the Flying Tigers expressly to fight the Japanese regardless of whether Japan and the United States were officially at war or not”. This version has apparently never been seriously questioned.

Buchan writes: “The historiography of the Flying Tigers remains puzzling, Why, for over 70 years, have historians so rarely called into question a narrative spun by wartime propagandists and post-war apologists of the Nationalist cause?”

One reason, surely, is that one messes with Wayne at one’s peril. The conventional narrative is appealing; debunking myths of rough-hewn American individualism is often a thankless task. The more prosaic truth that Buchan teases out is altogether messier.

There is something of a “Pony Express” quality to the Flying Tigers, something that took considerable planning, had a certain mythical quality to it, tapped into American views of itself, but in the end didn’t actually operate very long.

Book review: The Borrowed – Hong Kong crime novel’s six episodes tell a compelling story about city’s history

More significantly, the Flying Tigers seem to have been born of commercial rather than strategic or military considerations. The planes in question were the Curtiss-Wright P-40s (“Tomahawks”) to which Intercontinent had exclusive Chinese rights. Intercontinent had also set up the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (Camco) to assemble planes in China. One thing led to another (the situation was, to say the least, complicated) and in meetings with the US Navy in 1940, Leighton “outlined how his company could create on strictly commercial lines combat units manned by Western pilots” based in Yunnan.

Buchan’s account is full of the fog of war. Both Britain and the US wished to support China as a bulwark against Japan, but neither wanted to actually provoke Japan into war. The three sets of bilateral relationships never coalesced into a single coherent strategy.

Book review: The Chinese Typewriter – a masterstroke of linguistic history

The Chinese government desperately wanted an air force that wasn’t, in the term they used for what currently passed for one, “rotten”, and took assistance whence it was offered. The USSR waxed hot and cold; there were even official trainers from Italy. American planes allocated to (and paid for) by Britain were – to Britain’s annoyance – sneaked off to China. American president Roosevelt seems to have been ambivalent about the entire exercise, as well he might have been. And, in Buchan’s main conclusion, “the man behind the Flying Tigers ultimately was Winston Churchill”.

It was the British who “saw the strategic importance … for the defence of their colonies in the Far East” who were key to turning the group “into a combat unit”.

There is something to be said for debunking traditional narratives, and the Flying Tigers tale is an illuminating window (if something murky can be said to be illuminating) into the run-up to US entry into the war.

But Buchan also calls Intercontinent “an early private military contractor”. It is hard to read this account and not be reminded of the problems caused by the conflating of private commercial and national security objectives in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Flying Tigers were made up of “volunteers”, most of whom just happened to have previously been with US armed forces; the US government denied having anything to do with it – a modus operandi that looks similar to more recent stories that have emerged from Eastern Ukraine.

Buchan clearly likes some of the protagonists more than others; the non-historian cannot second-guess these judgments, but they certainly make for interesting reading. The villain of the book seems to be Lauchlin Currie, whose “official title of ‘administrative assistant’ belied his influence”.

Book review: Black in China – tales of Chinese racism hint at Sino-African race relations, but fail to show the bigger picture

Currie, in Buchan’s account, was in effect running his own pro-China foreign policy, not infrequently at the expense of the British, causing confusion that required others to step in and clean up after him.

History may be made of personalities – Buchan gives us a raft of them – but it is less comforting when policy is forged by personality rather than rigour.

Asian Review of Books

Coming soon in Post Magazine: author Eugenie Buchan tells the story behind her book