Book review: Fake news isn’t new, as The Formosa Fraud, fictitious Taiwan tale, reminds us

Graham Earnshaw has republished George Psalmanazar’s fictitious early 18th-century book about Formosa – now Taiwan – called A Description Of Formosa, which duped even the Bishop of London and a tutor at Oxford

by Graham Earnshaw

3/5 stars

If George Psalmanazar sounds like a made-up name, that is because it is. Psalmanazar, whose real name seems lost to history, was a Frenchman who claimed, with no small success, to be the first native of “Formosa” (a former name for the island of Taiwan) to visit Europe.

How Chinese Malaysian writers spurned at home found success in Taiwan, and why cultural identity is so often a theme of their novels

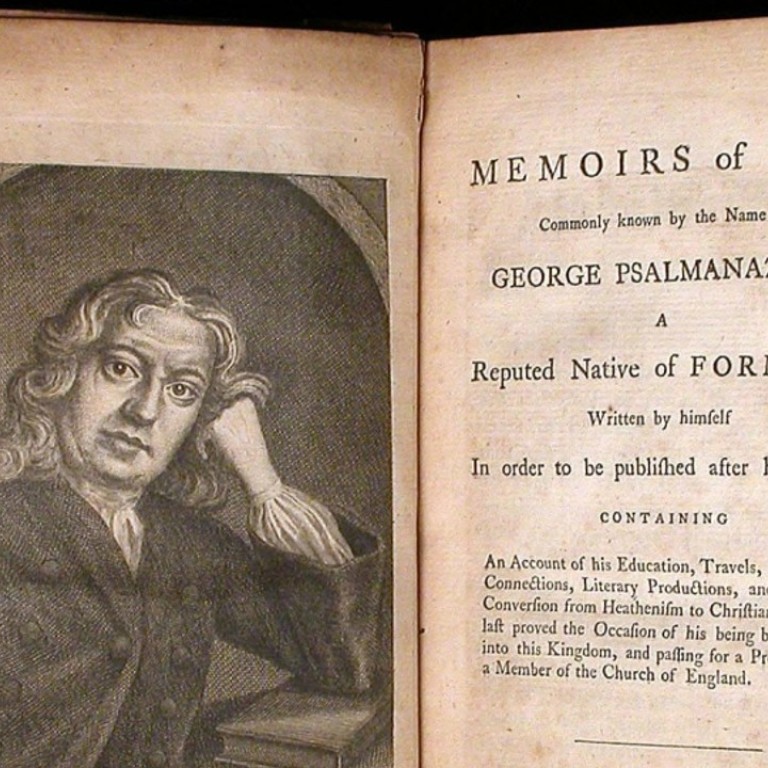

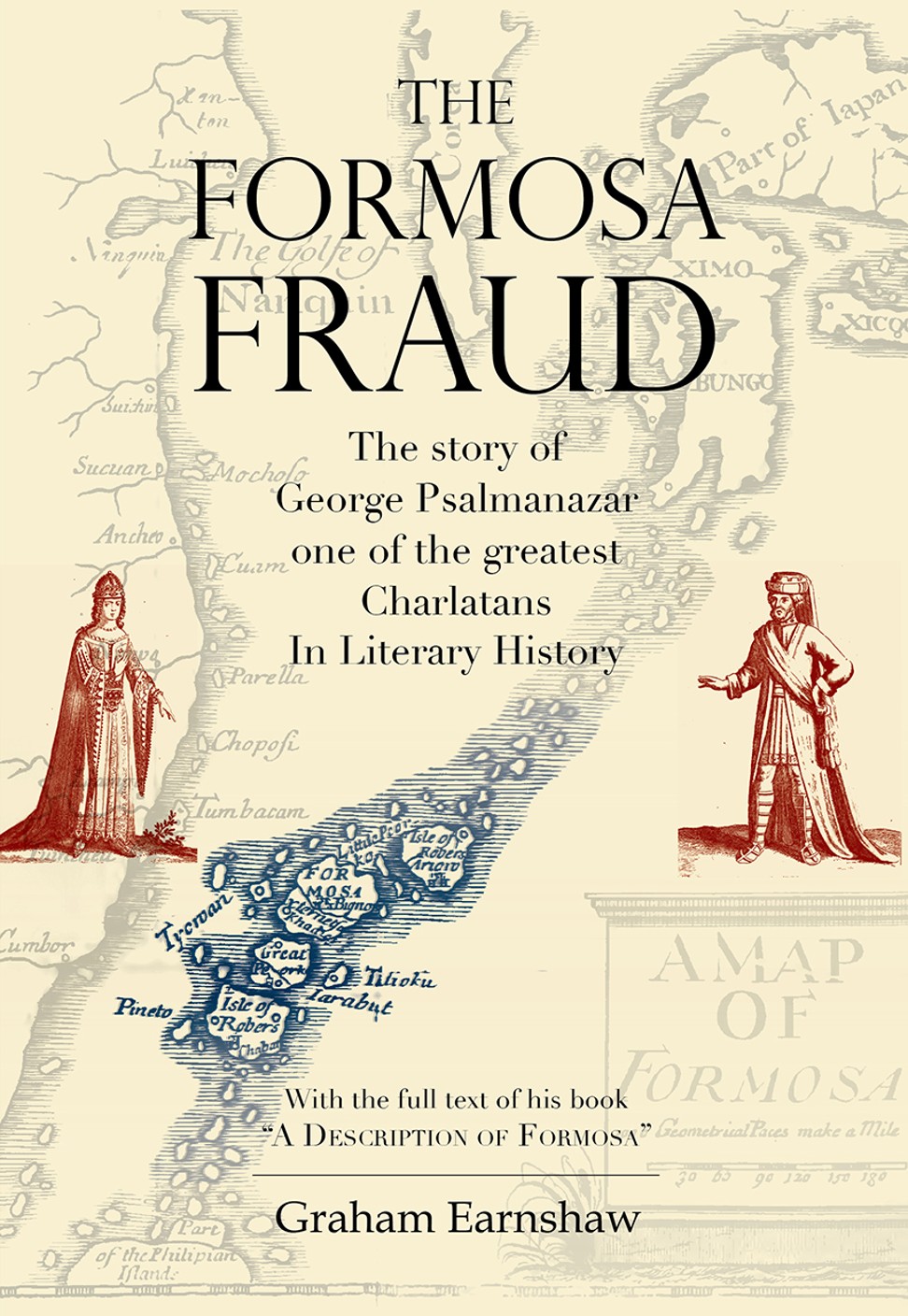

In his new book, The Formosa Fraud: The Story of George Psalmanazar One of the Greatest Charlatans in Literary History, Graham Earnshaw has republished Psalmanazar’s A Description of Formosa, first published in the first decade of the 18th century and, one assumes, long out of print.

Earnshaw has included a preface of considerable length and well as lightly annotating the text.

The story starts in the latter half of the 1600s: “George Psalmanazar was born somewhere around the year 1679, and while the exact date is not known, it was certainly not with that name.”

Psalmanazar, who seems to have had a certain gift for languages, bounced around Europe, had trouble with employment and women, at least once at the same time, and started making up increasingly fabulous backstories about himself, until he washed up in London.

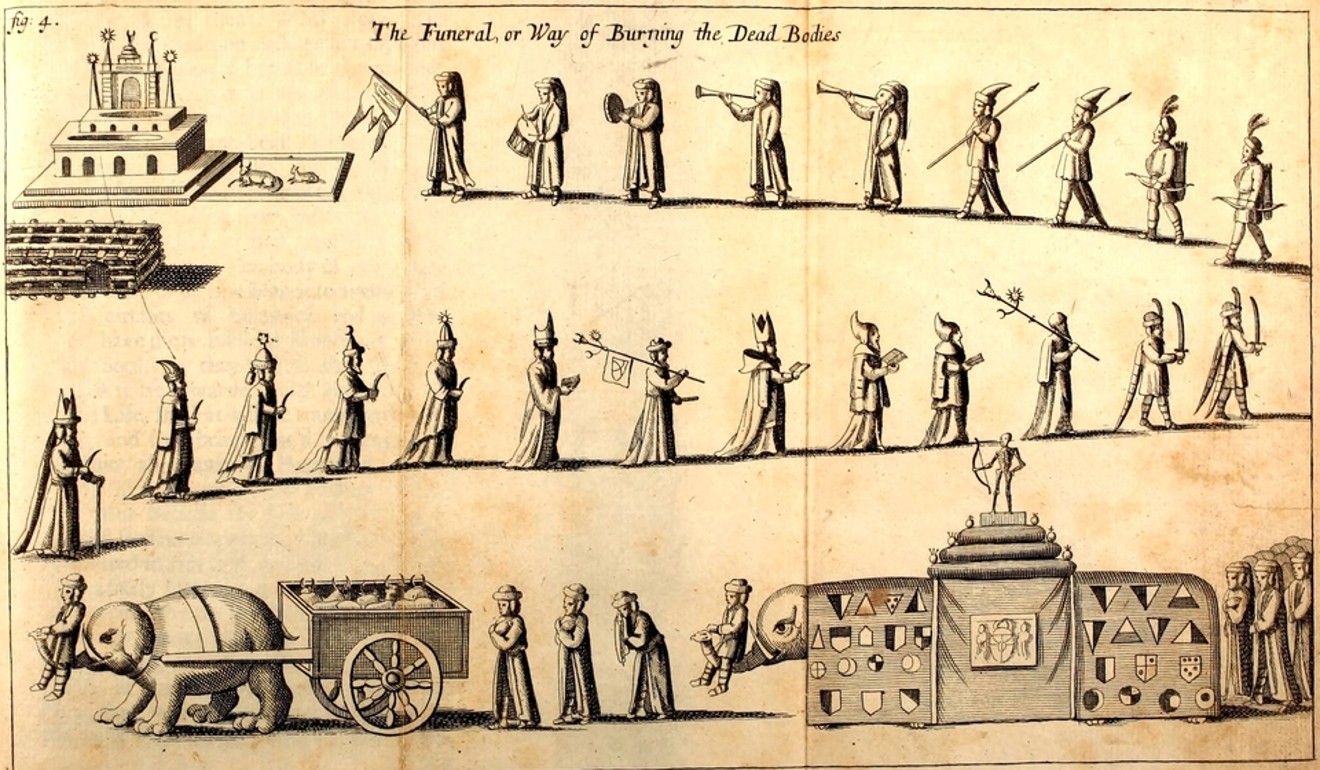

Earnshaw writes: “In 1704, a man appeared in England with the most extraordinary stories about Taiwan, or Formosa as it was then called. He said 18,000 boys are killed every year as part of Formosan religious ceremonies, the island is a major producer of gold and silver and Catholic priests are causing trouble there.”

The resulting book was such a success that it was republished the next year with a new introduction in which Psalmanazar saw off his critics.

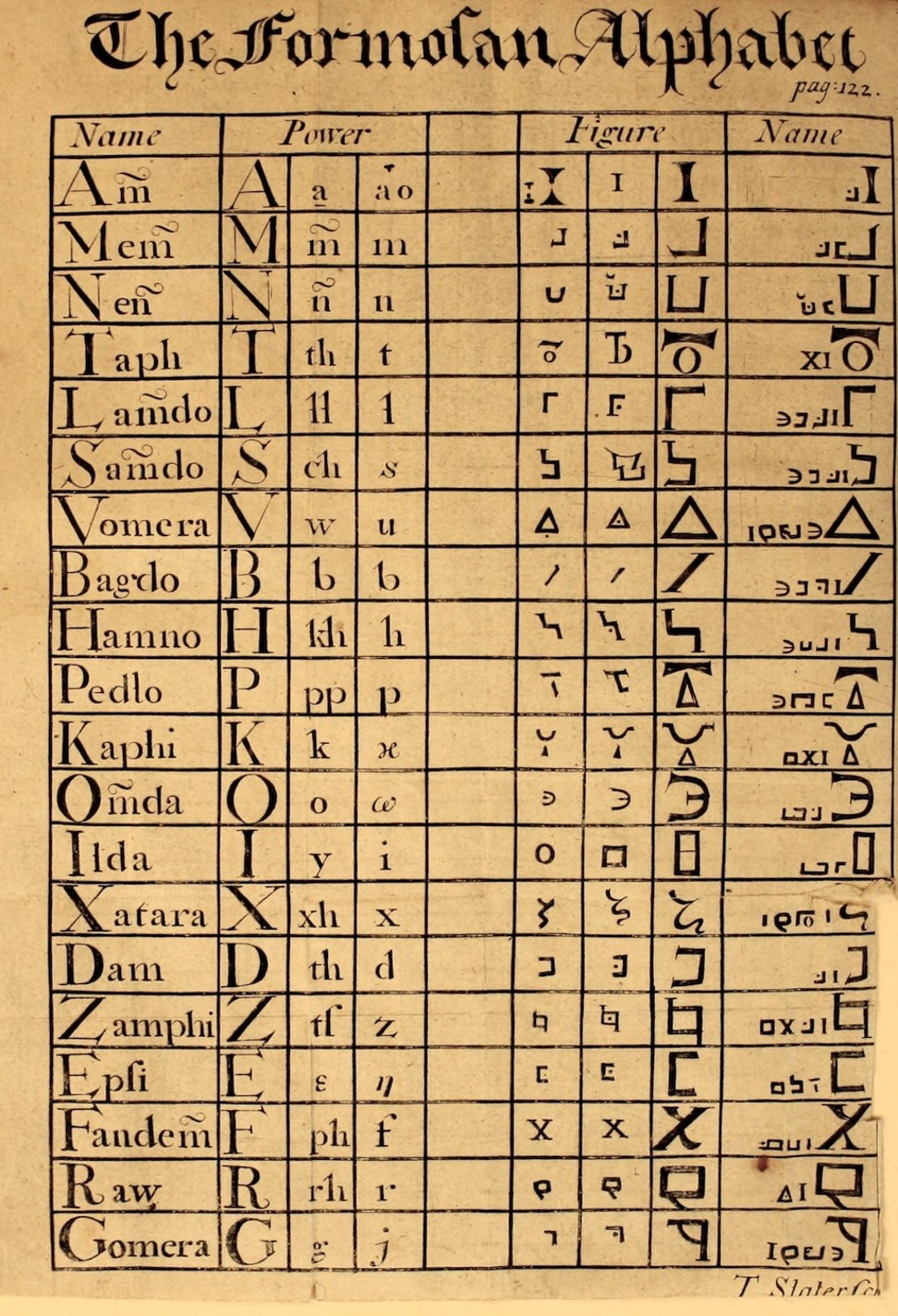

It’s all complete nonsense. Psalmanazar makes up an alphabet, a language (in case you were wondering, the first line of the Lord’s prayer in Formosan goes Amy Pornio dan chin Ornio viey, Gnayjorhe sai Lory), a religion, a social system and a whole stack of islands, all of which are described in considerable, entirely fictitious, detail.

One has to give the guy credit: when he made something up, he went all in. He also understood how extraneous detail makes an otherwise dubious statement sound plausible: “The language of Formosa is the same with that of Japan, but with this difference that the Japanese do not pronounce some letters gutturally as the Formosans do …”

2017’s best books: big-name writers returned to spotlight, and Liu Xiaobo’s untimely death casts a shadow

It beggars belief that anyone believed him at all, but at least some people, including the Bishop of London and a tutor at Oxford (where Psalmanazar was supposed to teach Formosan), apparently did. He was brazen in seeing off his detractors: when it was noted that his Formosa did not agree with extant written accounts, his response was this was proof of his veracity: “If I had been a fraud, he says, I would have been smart to base my description on the existing materials.”

However fun something this completely ridiculous may be, it’s nevertheless hard to make much of an investment in something that reads like a recent computer attempt to write Christmas carols.

Earnshaw’s deeper message is that fake news has always been with us and that people believe what they want to believe; he trots out a number of contemporary examples as well as Psalmanazar’s predecessors in literary fakery.

But Earnshaw is not above having a bit of fun himself: the book’s full title on the title page (“The story of the Fake Writings of George Psalmanazar, one of the greatest Charlatans in Literary History, With the full text of his book ‘A Description of Formosa’ and extra writings on his alleged travels and his spurious responses to sceptical objections”) is itself a take-off of long-winded titles of books of that era.

Book review: The War for China’s Wallet – readable if one-sided view of China’s business climate

Psalmanazar was soon found out, and gave the whole thing up, just like that. He seems to have found religion; he wrote on contract and seems to have become a close acquaintance of Samuel Johnson of all people.

It’s easy to laugh at Psalmanazar and the suckers who believed him. But don’t laugh too hard. The Psalmanazars among us today are not all quite as benign as he apparently was.

Asian Review of Books