Are rich alpha guys still sexy in Trump era? Romance novels reflect women’s changing fantasies

Sarah MacLean rewrote an entire book after Trump’s election because she couldn’t stomach her male protagonist. Meanwhile the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements are causing a profound shift in what appeals to female readers

In early November 2016, Sarah MacLean was 275 pages into writing her latest historical romance novel, The Day of the Duchess. She had hit all the right buttons – a titled (and entitled) duke; a beautiful, estranged wife touched by scandal; and an insurmountable challenge the pair had to mount before they could, well, mount each other.

Then Donald Trump was elected and MacLean couldn’t bear her hero any more.

“I woke up on November 9 and I was like, ‘I can’t write another one of these rich entitled impenetrable alphas. I just can’t,” says The New York Times bestselling author. “It was the story of that horrible impenetrable alpha evolving through love to be a fully formed human, which is a thing we do a lot in romance. And I just couldn’t see a way in my head that he would ultimately not be a Trump voter.”

Why educated, professional women in China aren’t marrying – new book explores the ‘leftover women’ phenomenon

Romance is a huge industry – the genre is worth more than US$1 billion in the US alone. Yet to some, it might seem a jarring relic among the current, wider conversations about sexual politics and gender equality. It is fair to say it is not the most respected of genres. Hillary Clinton recently described it as books about “women being grabbed and thrown on a horse and ridden off into the distance”.

MacLean, the author of 12 romance novels and a Washington Post columnist, was in a tight spot with The Day of the Duchess: the novel was due just three weeks after Trump’s election. She called her editor. “I said, ‘I can’t do it.’ It was a bad day. But my editor was also a wreck about the election and understood.”

So MacLean rewrote the entire book, giving extra context to the character of Malcolm Bevingstoke, the Duke of Haven. Now he is a changed man, one who works hard to get a second chance and earns it.

“In my early books I was willing to say they change over time,” MacLean says. “That book though, I was like, ‘I can’t even stomach this guy, he’s not sexy.’”

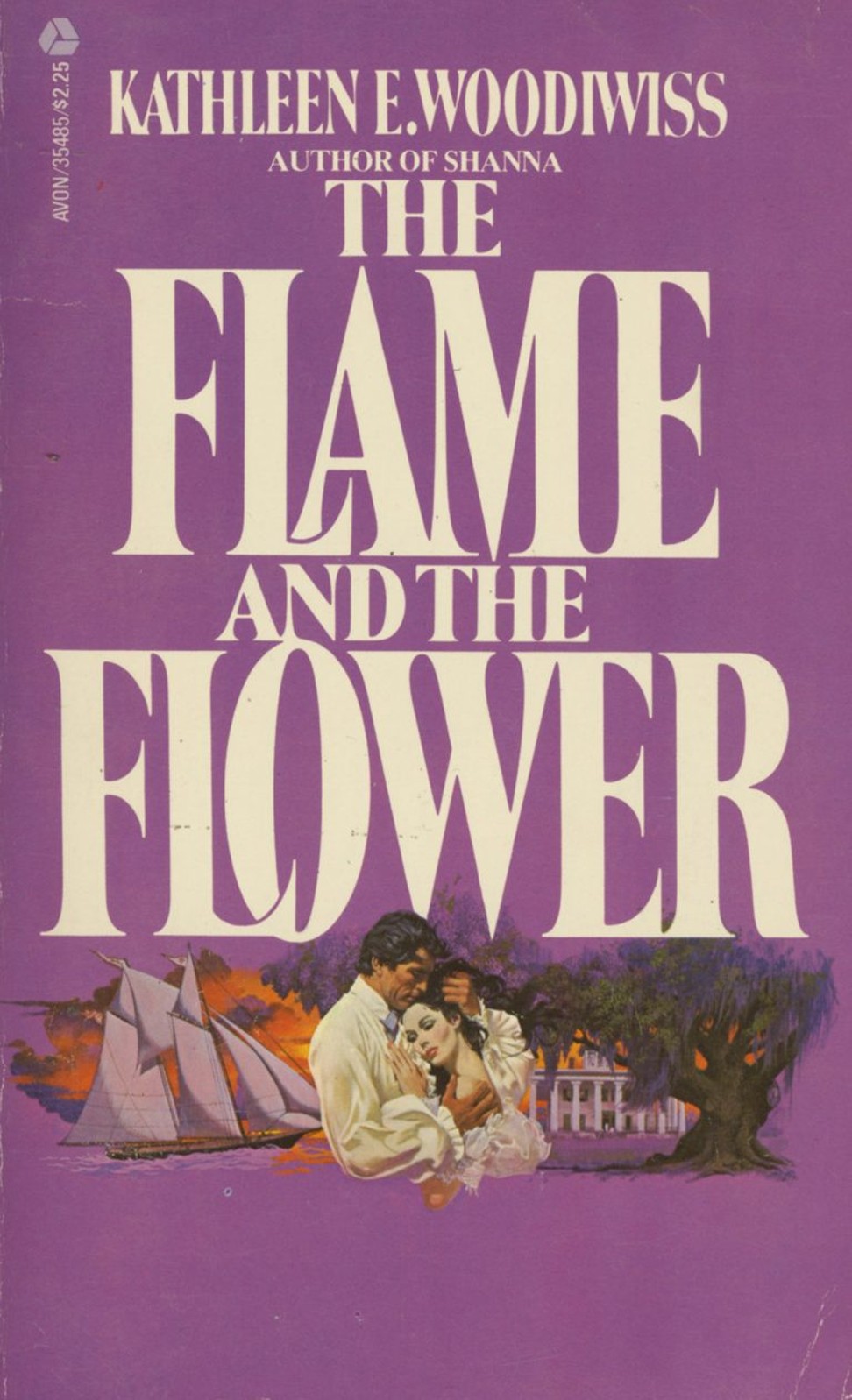

Romance has not always had much regard for empowering women. The Flame and the Flower by Kathleen Woodiwiss, a 1972 novel regarded as the first “modern” romance, sees the heroine raped four times in the first 100 pages. But then again, when it came out, marital rape wasn’t a crime, and single women could not get credit cards in the UK or US.

The genre has never been divorced from contemporary gender politics – “it is a representation of the women’s movement,” argues MacLean – and now authors and publishers are reporting a profound shift in the wake of the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements. Or, in MacLean’s case, Trump’s presence in the White House.

In the 1970s, the archetypal romance hero was forceful, controlling and sexually demanding; the workings of his mind were generally incomprehensible to the women he pursued. These days he might be controlling, but readers are more likely to be given reasons for his behaviour. Rape has not been a plot device for decades – and even when it was, MacLean says, there was a reason for it.

“The genre is often dinged for bodice-rippers’ forced seductions [but] there was a reason why heroines were thrown over the back of a horse. Even then, romance was feminist,” she says. In The Flame and the Flower, “you don’t choose to write that on the page if you’re not making a clear statement about what rape is and how the world treats women”.

Some romance tropes have remained constant over time. A quick flick through audio entertainment seller Audible’s categories reveals how specific readers can be if they want: books on bad boy princes, expectant princesses, childhood sweethearts, fake relationships, “best friend’s sibling” or “brought together by scandal”.

Rich heroes are big: a quick google throws up all sorts of novels about Greek tycoons and Italian billionaires. “It’s the fantasy that you’ll walk into a room and some guy will literally treat you like a princess … It was a clear trope – and then we elected a maybe-billionaire to president,” MacLean says. “And the way he treats women made that trope suddenly incredibly problematic.”

The fashions of romance have always changed over the years – they change with the fantasies that women and men want to have

Christina Hobbs and Lauren Billings are two US authors who write together under the name Christina Lauren. They have found themselves reassessing their first book, Beautiful Bastard, a 2013 erotic romance between an intern and her boss, as it is being adapted for television.

“He’s an ass and the female character is also an ass, so it works,” Hobbs says. “But because he’s the boss, it does have a little bit of the discomfort of the workplace. By the end it’s flipped, and she does have a lot of the power and I feel OK about it. But on television, it just would not fly now, so we really had to show the reason why he’s so cold and arrogant.”

How the woman who was history’s greatest pirate became a children’s story

E.L. James’s hugely successful bonkbuster Fifty Shades of Grey came out only seven years ago, but its questionable gender politics have begun to niggle at some; the recent film adaptation of the third book, Fifty Shades Freed, was criticised for being out of step with current sentiment.

“I remember what I was reading when I was stealing my mum’s books,” Hobbs says. “The heroines were like, ‘No, no, no,’ because they were supposed to be like that – ‘I’m supposed to say no until you talk me into it.’ Whereas in books now, the women are owning it.”

However, for all their new awareness, the two authors are clear that they don’t want to get in the way of anyone’s fantasies – most proclivities can still be catered to. “Every reader has their favourite trope and every reader has tropes they do not want to read,” Billings says. “There are readers who hate ‘second chance romance’ and readers who love ‘brother’s best friend’, but hate ‘surprise baby’.”

But women’s fantasies may be changing in the current political climate anyway. MacLean says the blue-collar hero has become more popular (“Mechanics are really big”). Anna Boatman, publishing director at UK-based publishers Piatkus, says career women have begun appearing more often in manuscripts.

“The fashions of romance have always changed over the years – they change with the fantasies that women and men want to have,” Boatman adds. “And maybe in the current climate, women are having different fantasies.”