Advertisement

Review | Ponti is a great Singaporean novel – compelling, evocative coming-of-age tale and portrait of a nation

Sharlene Teo’s novel, told through the voices of three women and its title short for pontianak – the man-hunting female ghoul of Malay legend – is a book to enjoy line by line, so vivid and spot-on are its descriptions and observations

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

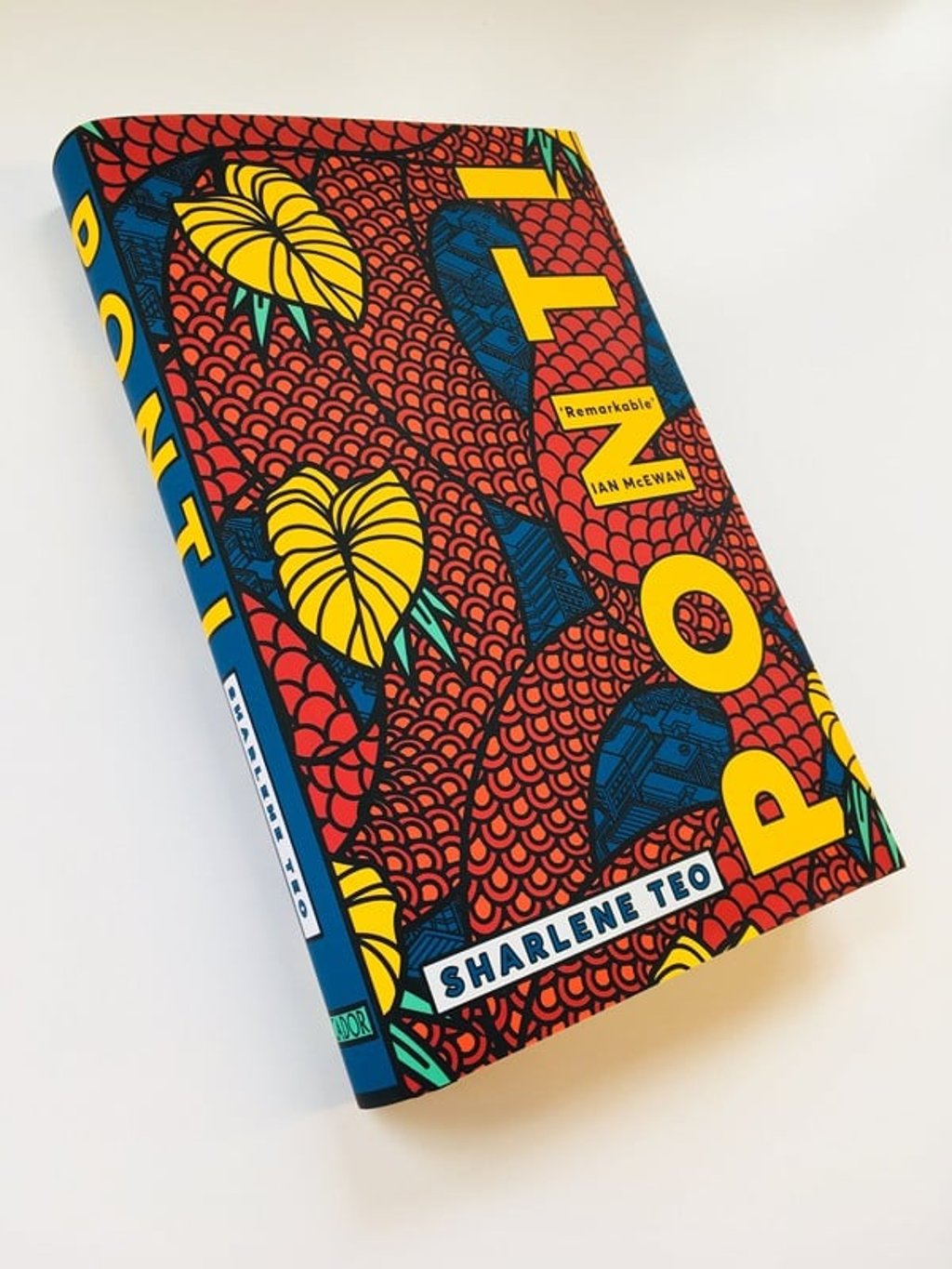

Ponti

by Sharlene Teo

Picador

Advertisement

4.5 stars

Advertisement

Sharlene Teo won the inaugural Deborah Rogers Writers Award (established in honour of the late London literary agent) in 2016 for an extract from her work-in-progress, Ponti, set in her native Singapore. The UK-based writer’s novel has finally been published.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x