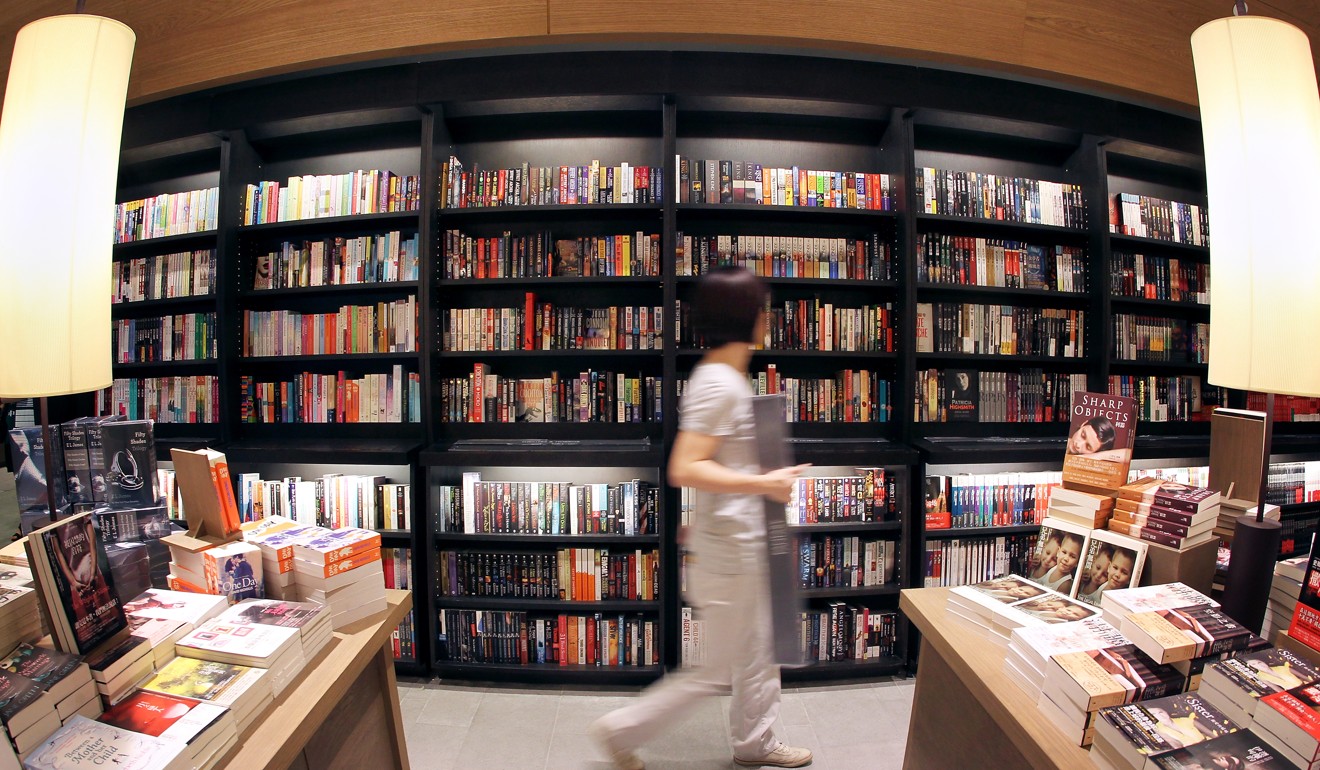

China bookshops offer an old-school reading experience in the digital age

Amazon may have changed the book industry with cheaper online offerings, but a new generation of physical bookstores in China are bucking the trend, offering coffee, free Wi-fi, comfortable sofas for readers and even art classes

Hidden away between rows of restaurants in the basement of a high-end Chongqing shopping centre is a rather surprising find. An arty and sleek bookstore stretches out over a sizeable 2,500 square metres, full of leather sofas, comfortable reading spots, plants, and a broad range of books from Chinese classics to international bestsellers.

The shop is one of the first physical stores opened by online bookseller Dangdang, bringing together books with space for talks and discussion groups, a cafe and even art classes.

“I want my children to get used to reading books both for study and fun,” says another woman, who has brought her three-year-old daughter to explore the large children’s book area.

Dangdang’s shift to bricks and mortar reflects a global trend, and in China a new generation of meticulously designed bookstores are breathing new life into the publishing world.

Smartphones are the preferred way to consume almost all media in China, from news to soap operas – more than 90 per cent of millennials own a smartphone, and they use them for an average of almost 30 hours a week.

China’s online publishing industry – where fortune favours the few, and sometimes the undeserving

Despite this, physical bookstores are riding a wave of popularity, particularly privately owned stores.

“The market for bookstores has changed significantly in the past decade, both globally and in China,” says James Hawkey, head of retail for real estate services firm JLL China.

“In the US, Amazon first decimated the traditional bookstore by providing something cheaper and more convenient online, and it’s now reinventing the traditional bookstore. In China, the story has been rather different. Historically, Chinese books were very cheap, publishing wasn’t a money spinner, and bookstores were functional at best.”

China’s bookshops are having to adjust to their consumers. As China’s shopping malls dedicate space to “experiences”, this means a new generation of bookstores with reading spaces, art galleries, cafes, retail space and Wi-fi.

“I think physical books offer an alternative set of experiences that are becoming attractive to young people used to consuming their information digitally,” says Jonathan Sullivan, director of the China Policy Institute at the University of Nottingham.

“The feel of a book in hand, browsing a bookshop, taking a book to a cafe, might sound like common experiences, but they aren’t common to many people. But with increasing prosperity, more facilities, and an increasing focus on lifestyles, books are en vogue.”

Why China loves Jane Eyre, whether as a feminist manifesto, a history of colonialism or just a simple children’s bedtime story

One of the first to raise the bar in China was Taiwanese chain Eslite. It was followed by other new entrants to the market including Muji Books and Mix Paper in Shanghai, while elite bookstore chain Fang Suo Commune now has huge outlets in cities from Guangzhou to Chengdu.

“Go to Eslite in Suzhou and you’ll see that people browsing the shelves in a comfortable space with a modern, quality aesthetic are there for the experience. Otherwise they’d pay a much lower price online,” says Sullivan.

“Emphasis in China is changing to experience, as it is in the West, as many people move away from materialism to lifestyle.”

“Many landlords acknowledge that these new bookstores bring huge benefits to a large shopping centre: they are a great generator of traffic, as books still have broad appeal even in the age of the internet. They provide a cultural anchor for the project, and they look spectacular,” says Hawkey.

Bestselling Beijing murder author turns to Shanghai in the 1930s as inspiration for latest tale

In addition, the finances do not always add up. While urbanites might like to visit bookstores, they aren’t always buying much. According to OpenBook data, sales tracked through online bookstores grew by 29 per cent in 2017, while bricks-and-mortar bookstores sales grew by only 2.3 per cent.

But for devotees of the new generation of bookstores, they are an important part of the urban fabric.

“It’s more than just a bookshop – it’s a peaceful place to spend time, have a coffee, think of new ideas,” one Shanghai woman says as she checks out art books on the second floor of Shanghai’s Mix Paper. “This city gets busier and noisier, and we all need places to relax.”