Porn star’s book aims to put the record straight on pornography – because it’s here to stay

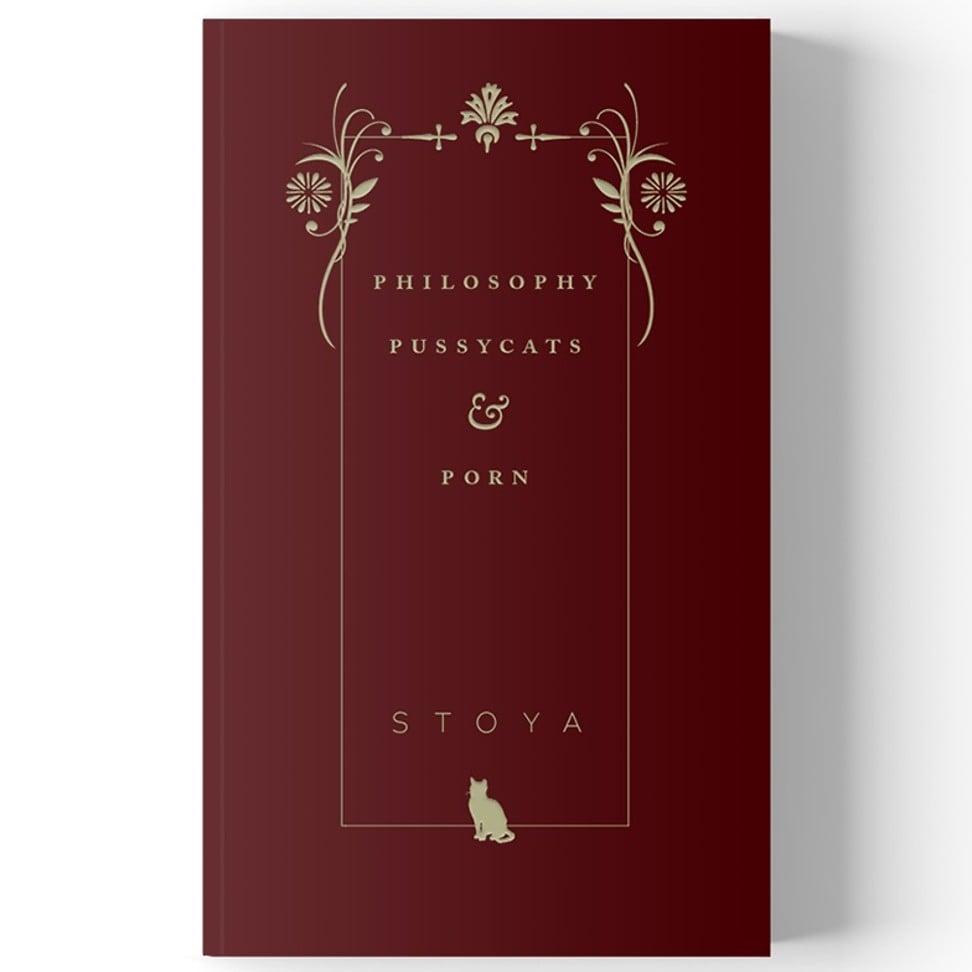

Stoya, an award-winning performer in adult films, says her book, Philosophy, Pussycats and Porn, is an attempt to find a ‘serious language’ when it comes to discussions about sexuality

Dubbed “the pop star of porn” by Village Voice, Stoya is an award-winning performer in adult films, a director, a podcast host and an all-round entrepreneur. She is both a vocal defender of the porn industry and one of its most nuanced commentators.

“When I first considered performing in a hard core pornographic video, I also thought about what sort of career doors would close once I’d had sex in front of a camera,” she mused recently in The New York Times.

Finding freedom in colonial India

“Being a schoolteacher came to mind, but that was fine, since I didn’t want the responsibility of shaping young minds. And yet thanks to this country’s non-functional sex education system and the ubiquitous access to porn for anyone with an internet connection, I have that responsibility anyway.”

So her first collection of essays and articles is Philosophy, Pussycats and Porn, an eclectic mix of biographical vignettes and reflections that covers subjects from religious iconography to technology, but often circles back to sexuality, patriarchy and identity. “When you spend 12 years with your entire job being sexuality,” she says, you start to find all sorts of odd little angles that people aren’t really talking about.”

Stoya began writing when she grew tired of what she calls “parachute journalists” – those who report on subjects they know little about – “getting it so incredibly wrong with porn”.

My relationship with feminism is a little fraught because there’s a certain, very loud, segment of feminism that hates ... heterosexual behaviour, hates sex work, hates porn

Tired of her own words being truncated in interviews, she realised she could write the articles herself. And she has a clean, functional prose style, punctuated by understated wit and insightful digressions, the latter a nod to her grandmother’s conversational style (her nom de plume is also a nod to her grandmother’s Serbian surname).

Stoya frequently performs an intellectual hopscotch from topic to topic. In one essay, she goes from a burlesque troupe to a Soviet variety of Kinsey report, before arriving at the question: “Do the political systems of a population change the dynamics of group sex?” She casually drops one-liners that could be essays in themselves.

One such line is in the essay “Squicks and Squees”: “the semantics of sex”. “We don’t have serious adult language for serious adult discussions of sexuality,” she says. This is a problem because, as she puts it, “language informs perception … We have specialised clinical words, like penis, cervix, digital penetration. And we have ‘locker room’ language … but we don’t have words in the middle.”

Even the term “pornography”, as Stoya pointed out in her 2014 contribution to the academic journal Porn Studies, is slippery: it’s applied to a “broad spectrum of aesthetics, sexual acts and target audiences”. Not to mention a variety of media. “For porn to be of any positive use in the world, we need to start defining what exactly it is,” she says. Even the distinction between sex and porn is not as clear as we think, as she writes in Graphic Depictions, Scene 01, “because all partnered sex involves observation of some kind, though not necessarily visual”.

The distinction between reality and realism is recognised in literary or film criticism, but less so with pornography (despite the fascinating attempts of a few notable academics). “We’re able to look at a battle between Marvel superheroes and go: ‘This is a fantasy. This is fiction’,” she says. And what is and isn’t porn is a debate with real consequences. In one essay, she recalls being asked by a photographer for the dividing line between nude modelling and porn.

She instead catalogues the day-to-day impact that being classed as a pornographer – rather than a model – will have: being refused a PayPal account; getting a hard time from banks; being unable to get a business loan.

“It’s only really porn,” she writes, “when you wake up in the middle of the night worrying about a spelling error on the 2257 age verification documents … when you dread some kind of cop busting in demanding to see that paperwork.”

Half the time, when trying to rent an apartment in New York, Stoya will be turned away once the landlord learns of her line of work. The rest of the time, she is asked to pay a year’s rent upfront. “Fortunately, I’m able to do that,” she says. Others can’t, which forces them into less than favourable living conditions. “In the US, discrimination laws are tied up with whether the identity [in question] is a choice or not. So sex workers are not protected because we made a choice to go into it,” she says.

Stoya is sometimes referred to as a feminist icon of “alt porn”: a contentious term for material that differs from mainstream tastes. But she doesn’t think her pornographic work is specifically feminist; in fact, she claims it would be “pink, sparkly washing to try to pretend that it is”. Especially when she could list many other women making actively feminist porn. Women such as Erika Lust, Ovidie, Madison Young or the late Candida Royalle.

“My relationship with feminism is a little fraught because there’s a certain, very loud, segment of feminism that hates heterosexuality, or heterosexual behaviour, hates sex work, hates porn,” she says. She has some sympathy for the second-wave feminists that are often aggressively against her pornographic work.

Arundhati Roy releases first novel since Booker win 20 years ago

“Those women had to fight so hard that I can understand how they’ve ended up with rigid thinking,” she continues. “But, especially as a young woman, it was a real headf***. Like: ‘You can be anything you want to be, except f*** you for wanting to be that.’ I thought female sexuality was an OK thing? And maybe something beautiful to embrace? ‘Oh, but only within these very narrow areas where it’s considered OK’.”

But porn isn’t going anywhere; as Stoya says, paraphrasing an argument from sex educator Annie Sprinkle: “The answer is not to get rid of porn, it’s to make better porn.” And if academics don’t heed her call, Stoya may take matters into her own hands. “Maybe that should be my second book,” she jokes.