Anuradha Roy captures India’s growing pains as fictional and famous lives grapple with love and loss

In Roy’s second novel involving early 20th-century history in India, war, nationalism, and drama collide in unforeseeable ways as famous figures and an emerging country get to grips with enormous transformations

“Who among us does not have friends – men and women thought to be moral and humane – that have closed their eyes to the brutal amorality of the ruling regime, seeing it instead as the political road to India’s salvation?” she wrote on the Wire, an Indian news website earlier this year, in response to a high-level campaign to absolve eight men of the rape and murder of an eight-year-old Muslim girl.

An Irishman in colonial India’s ill-fated enterprise

And of the current political situation in India she says: “Inequality here has never been more catastrophic, but I think the very people the rightwing are trying to crush into nothingness are the unstoppable forces now – women and Dalits, people from the lower castes – battered but undefeated. In the past 70 years there has been such profound social change that there is no going back to the dark ages the right is trying to return us to. If I did not believe that, it would be hard to live.”

Such journalistic broadsides might lead one to expect that her novels would be equally polemical, but the longlisting of her third novel for the Man Booker prize in 2015 drew the world’s attention to a singular novelist capable of combining a no-holds barred analysis of India’s sexual hypocrisies with a delicate social comedy involving three elderly women on a temple pilgrimage.

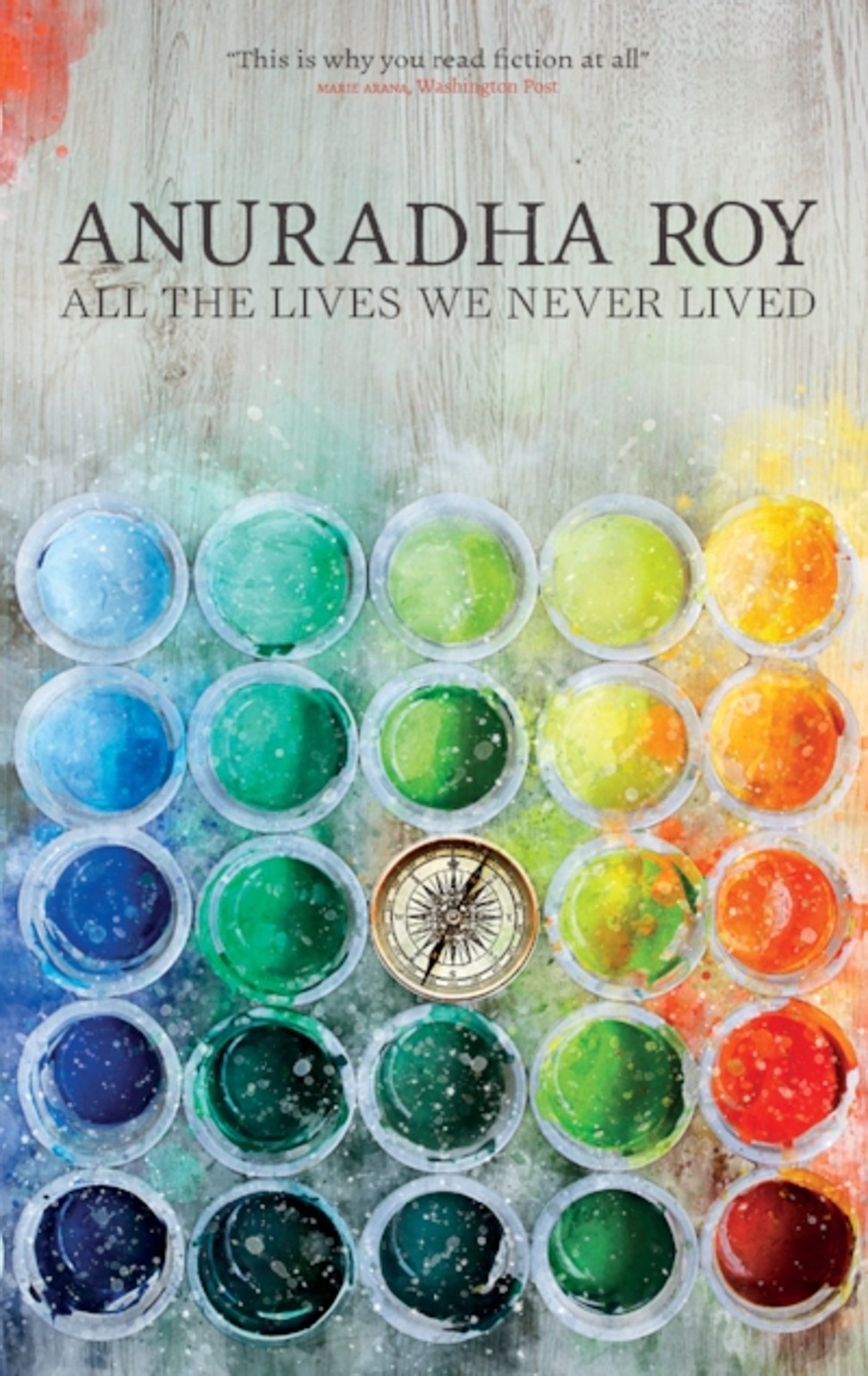

Where Sleeping on Jupiter was sharp and contemporary, her latest novel sounds a more melancholy note. All the Lives We Never Lived is set against the tumultuous history of the 20th century, as India is dragged into a war that is not of its making and then abruptly liberated of colonial rule to make what it can of independence.

Sydney Percy-Lancaster, the Anglo-Indian horticulturalist, is one of several characters from history in the novel, along with the poet Rabindranath Tagore and the German painter and curator Walter Spies. Roy feeds the words of these figures – gleaned from diaries, letters and newspaper columns – through the consciousness of Myshkin, a fictional apprentice to Percy-Lancaster.

Roy, who writes in English but speaks “Bengali with my mother”, Hindi and English with her husband and “Hindi to the dogs”, was well-placed to process this source material – some of which hadn’t been read for nearly a century. “I really felt when I was writing this book that all sorts of windows were opening up in my head,” she says, though she was aware of the risks of over-researching. “When you’re writing a historical novel with historical figures you can become burdened by the demands of authenticity. I wanted it to sit quite lightly.”

I really felt when I was writing this book that all sorts of windows were opening up in my head

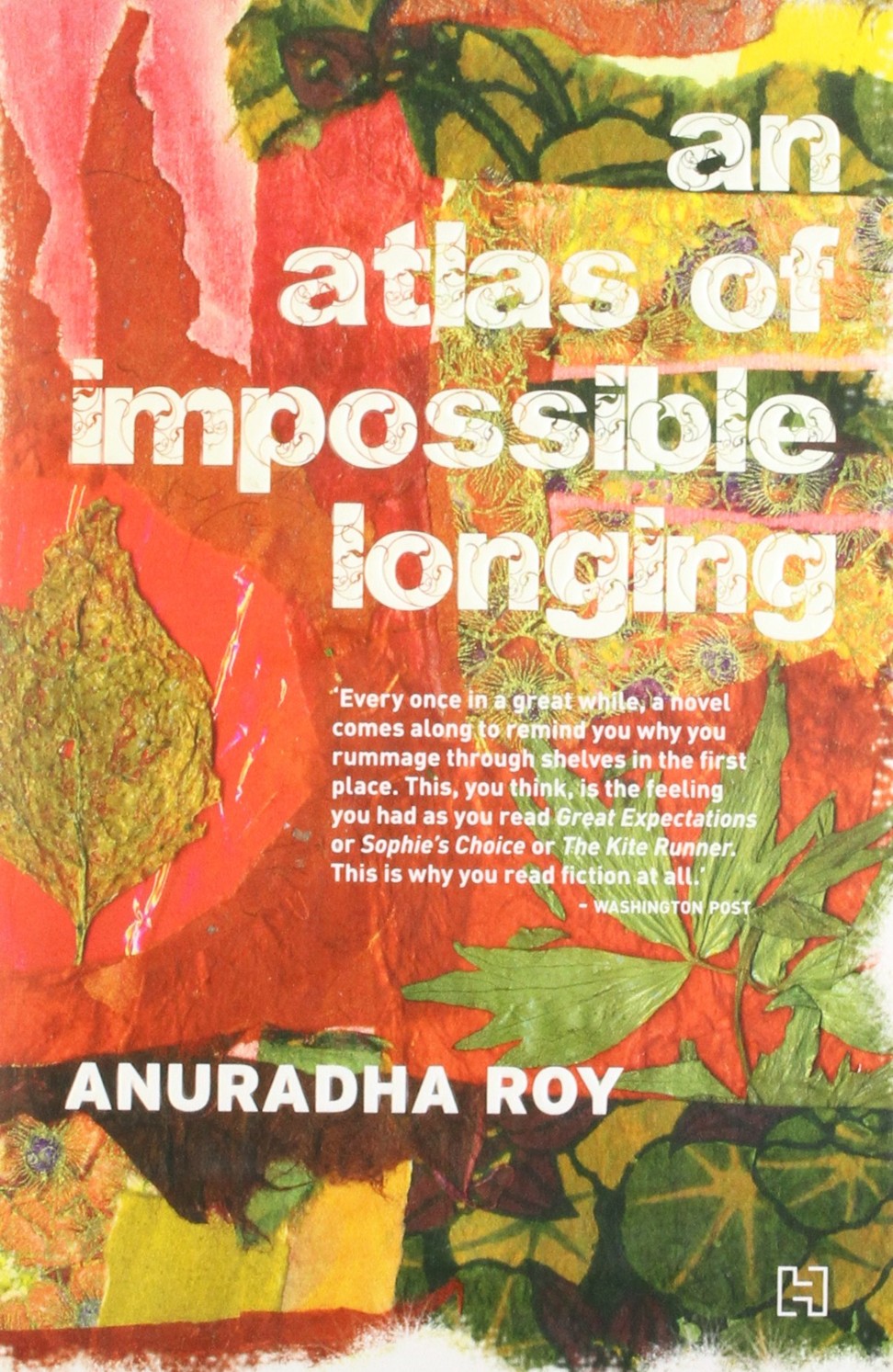

Her first novel, An Atlas of Impossible Longing, also covered India’s early 20th-century history, though without the complication of real people. Published in 2008, it told the story of three generations of a Bengali family whose disintegrating houses speak of their faltering ambitions and fortunes – from a colonnaded riverside villa, in constant danger of being swept away, to a secretive forest house with its back to the road.

Roy herself lives on a remote hill farm in the Himalayas with her publisher husband, and the story of how they came to be there could come directly from one of her novels. Born in 1967 in Calcutta, the younger of two children, she spent her infancy living in makeshift camps as the family followed her field geologist father around some of India’s remotest regions. A picture of her mother washing clothes in a river while Anuradha and her brother look on from boulders attests to the material hardship behind this childhood idyll.

The sudden death of her father when she was seven years old grounded the family in Hyderabad, where she went to local private schools before landing a university place to study English literature in Calcutta. As the future loomed with nothing obvious to fill it after graduation, she and a group of girlfriends dug out an old typewriter and decided to apply to Oxford and Cambridge “for a lark”. To her astonishment, they wrote back and she found herself enrolling for a second English degree at what was then New Hall (now Murray Edwards College), Cambridge.

Ovidia Yu’s Singaporean sleuth continues to entertain – book review

After returning home for a while to look after her mother – “my father’s death was still raw for her” – she moved north to Delhi and landed a job with Oxford University Press (OUP), where she met a promising novelist turned star editor, Rukun Advani. For three years they worked together, until he was offered a writing residency in Scotland, and she could only get a visa to join him as his wife. When they decided to get married, there were difficulties: Roy says she was informed that OUP policy prohibited married couples from working together (although OUP disputed this). She left the company and Advani resigned in protest.

“It was absolutely ghastly. We had no money. They even took the car back before we could clear out our stuff,” Roy recalls. As the news spread, outraged writers began to cancel their contracts. “One of them said they’d left OUP, so what were we going to do about it?” So began Permanent Black, the academic publishing company which the couple founded in 2000. They named it after the ink pens they both liked to use, but also to honour their sense of “otherness … It felt like a different colour and identity from the very elite white publishing in the west.”

Permanent Black now publishes around a dozen books a year, and has a backlist of more than 400 titles, with Roy doing the design and publicity while Advani looks after the editing, rights and accounting.

Roy writes in the mornings and afternoons, spends the evening on her design work, and now has a second cottage dedicated to her pottery. She doesn’t sell it, she says, “because if it’s beautiful I wouldn’t want to part with it and if it’s ugly nobody would want to buy it”, but it means that she drinks her morning coffee from a pot she is made herself.

In All the Lives We Never Lived, Myshkin recalls his battles with his activist father. “Could I really not see what a gigantic project there was ahead for every young, patriotic Indian. Was I blind? When our just-freed country had to be pulled out of poverty, hunger, violence, illiteracy – what I wanted to do was grow flowers?”

Conformist at work, a misfit outside: meet Convenience Store Woman

“Here we have rain,” she writes. “I am briefly in Delhi, green and monsoony, and saw a peacock pirouetting in a garden yesterday, which transformed this grubby old city in one second flat.”