Graphic novels: how to see, read and appreciate them, in all their rich variety

The range and variety of graphic novels continues to expand, and whether or not Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina makes it to the Man Booker prize shortlist, they are here to stay

The recent fuss about the Man Booker prize’s longlisting of a graphic novel for the first time, the chilling, understated Sabrina by Nick Drnaso, may have piqued your interest in exploring this ever-expanding medium further, or perhaps for the first time.

Not everyone has grown up reading comics, and the demands of their various verbal and visual literacies can take some adjusting to, particularly if you’re used to the orderly typesetting of prose novels. It’s never too late, though, to try stretching your brain – both sides of it when it comes to graphic novels, where looking is as important as reading.

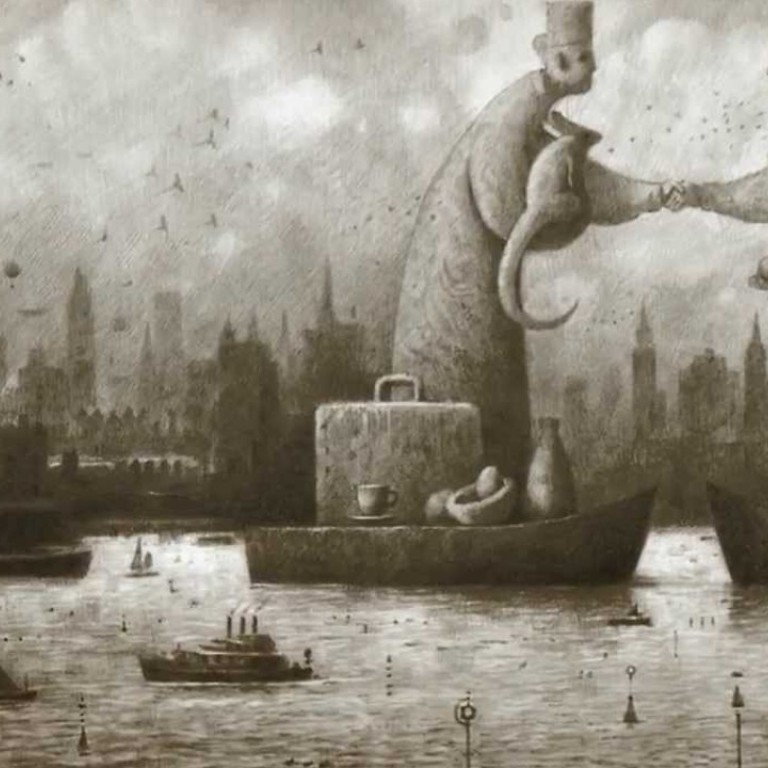

This experience comes through in the wordless migration parable The Arrival by Shaun Tan (2006), which follows a man who has gone on ahead of his wife and children to seek work abroad and struggles to navigate his alien surroundings and their indecipherable language.

Unable to make himself understood, he resorts to making simple drawings to communicate his need for a room. The reader shares his bafflement and gradually grasps with him how his strange new homeland works. Tan’s genius in children’s picture books blossoms in this extended tale for all ages, illustrated in almost photographic sepia images.

Charles Burns is a true artist of the graphic novel

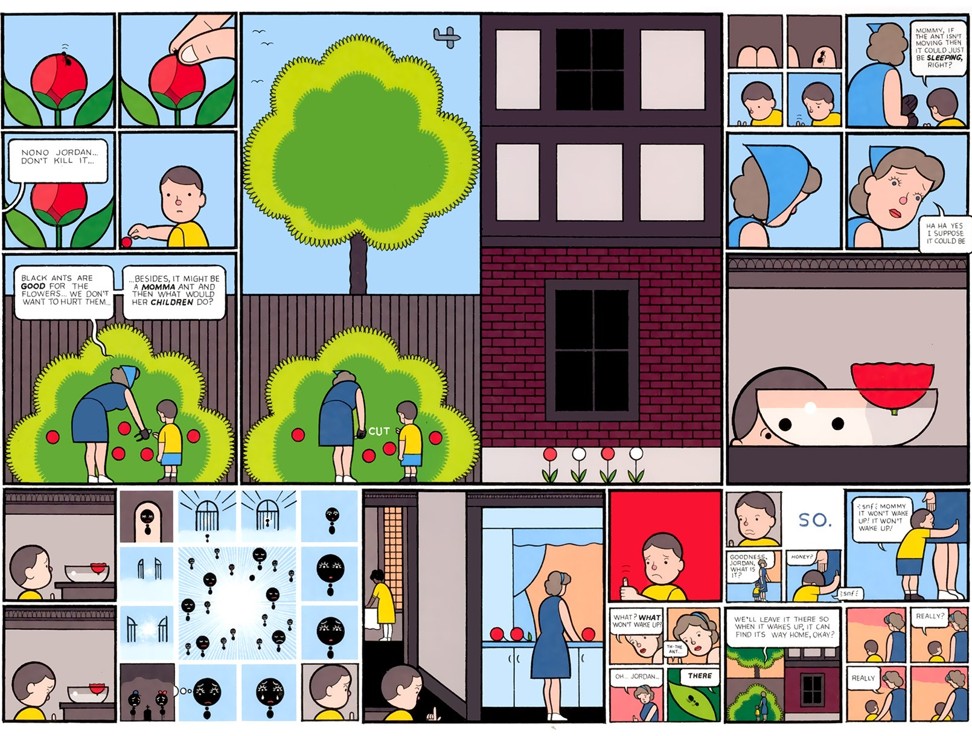

One lifetime’s dawning awareness and evolving cognition is graphically and poetically conveyed in Chris Ware’s Acme Novelty Library #20 (2010): Lint is an approachable introduction to Ware’s oeuvre (a key influence on Drnaso). From newborn child to anguished adolescent, to career, marriage, fatherhood and decline, each year of Lint’s life is distilled into an intricate, humane diagram of a few telling moments of consciousness per page.

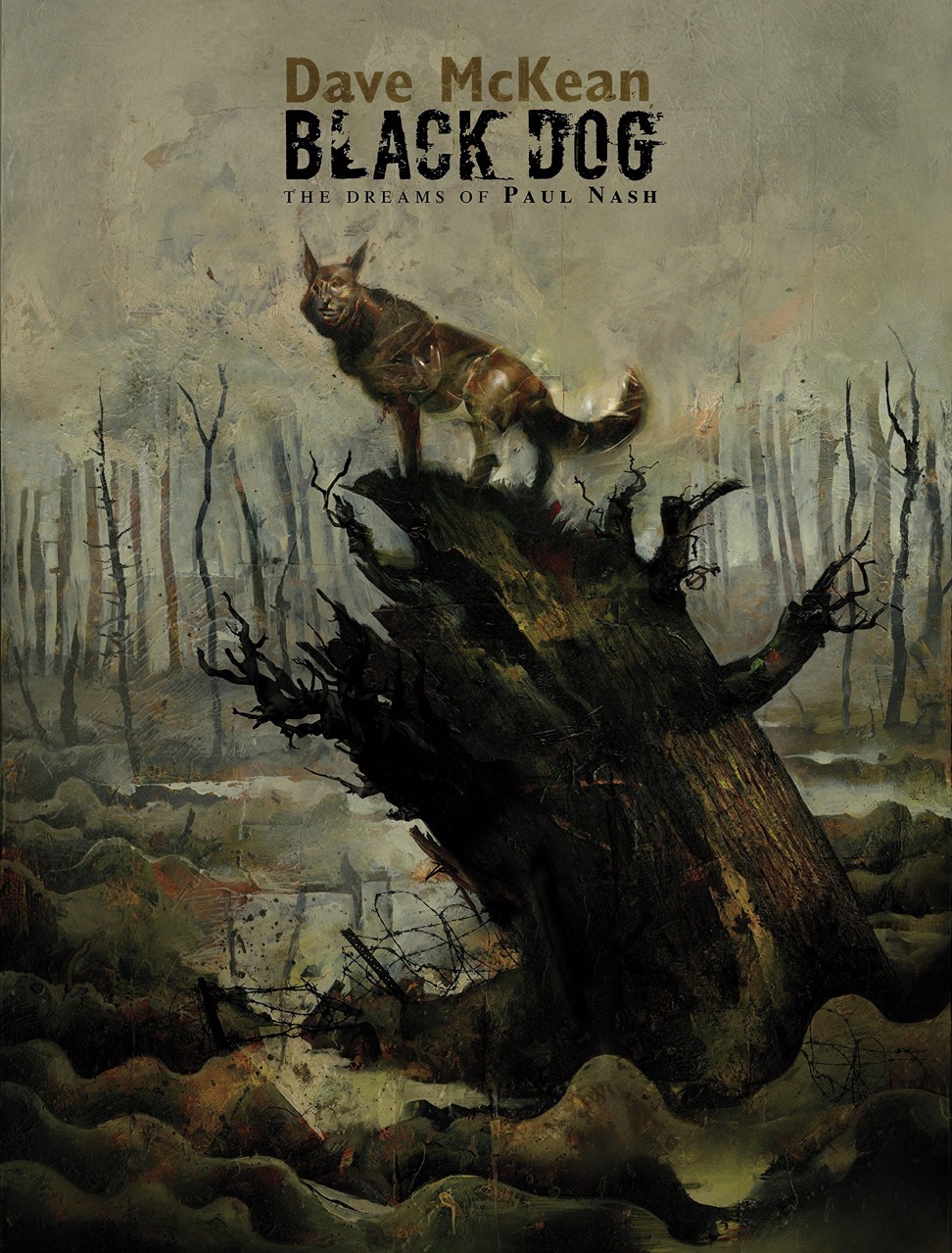

In comparison, it takes 15 revelatory dreams to unfold the troubled biography of British first world war artist Paul Nash in Dave McKean’s Black Dog (2016). Inspired by Nash’s artworks and writings, McKean harnesses an array of media, palettes and styles to explore his subject’s fluid psychological states.

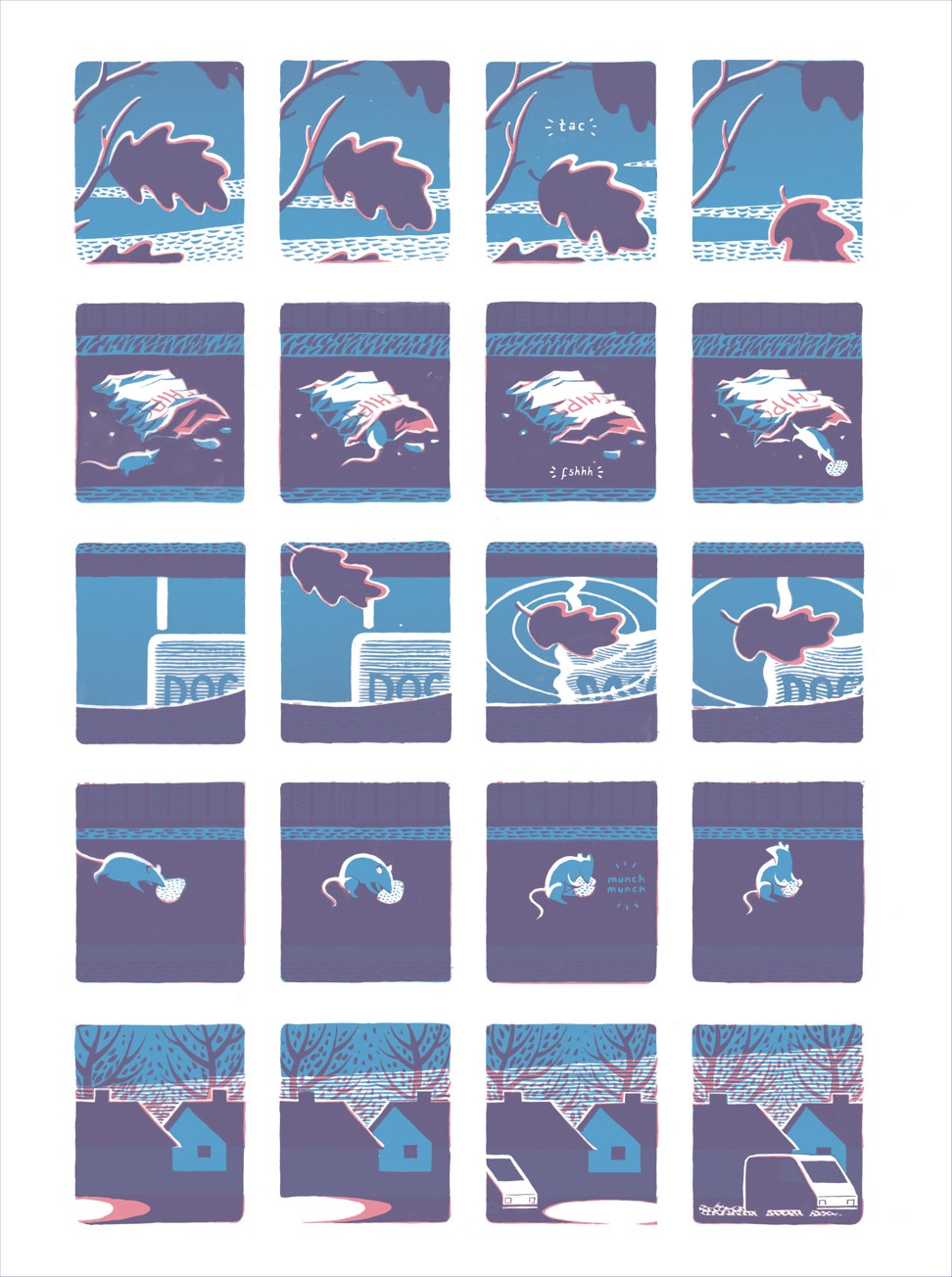

Time becomes space in comics, enabling us to freeze and ponder the most fleeting micro-expression or falling leaf. In The Walking Man (1992), Jiro Taniguchi invites us to accompany a middle-aged Japanese man of few words, as he sidesteps Tokyo’s bustle and seeks solace in the natural world, finding a hidden glade or a remembered cherry tree from his childhood. Taniguchi’s serene pace and tenderly rendered settings underscore the zen-like calm.

Patience by Daniel Clowes – a deeply stirring graphic novel

A similarly subtle, sublime mood is evoked in printmaker Jon McNaught’s Pebble Island (2012). A wordless comic, its shifting sunlight, bleak, dramatic seashores and boyish sense of wonder are derived from McNaught’s fond memories of living in the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean.

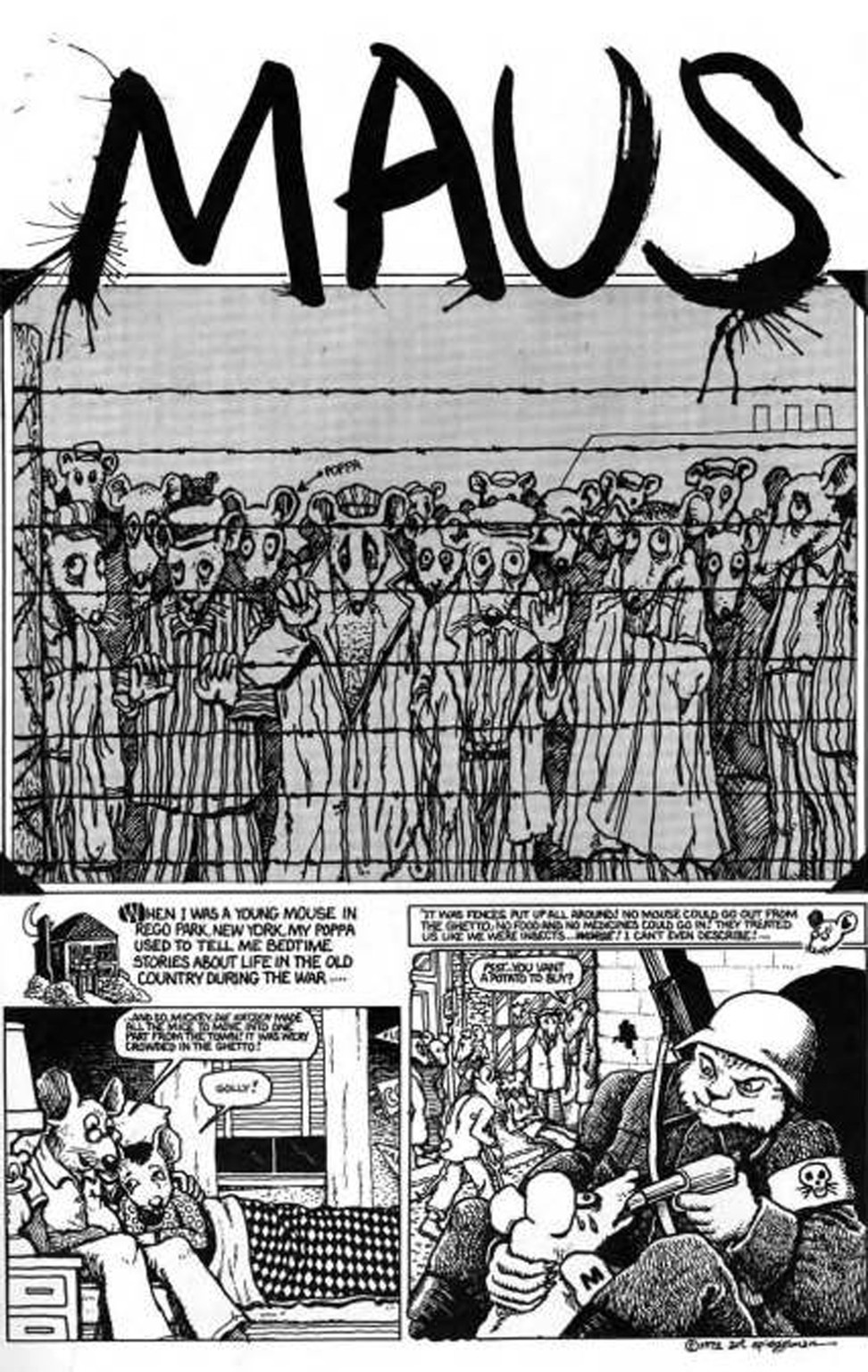

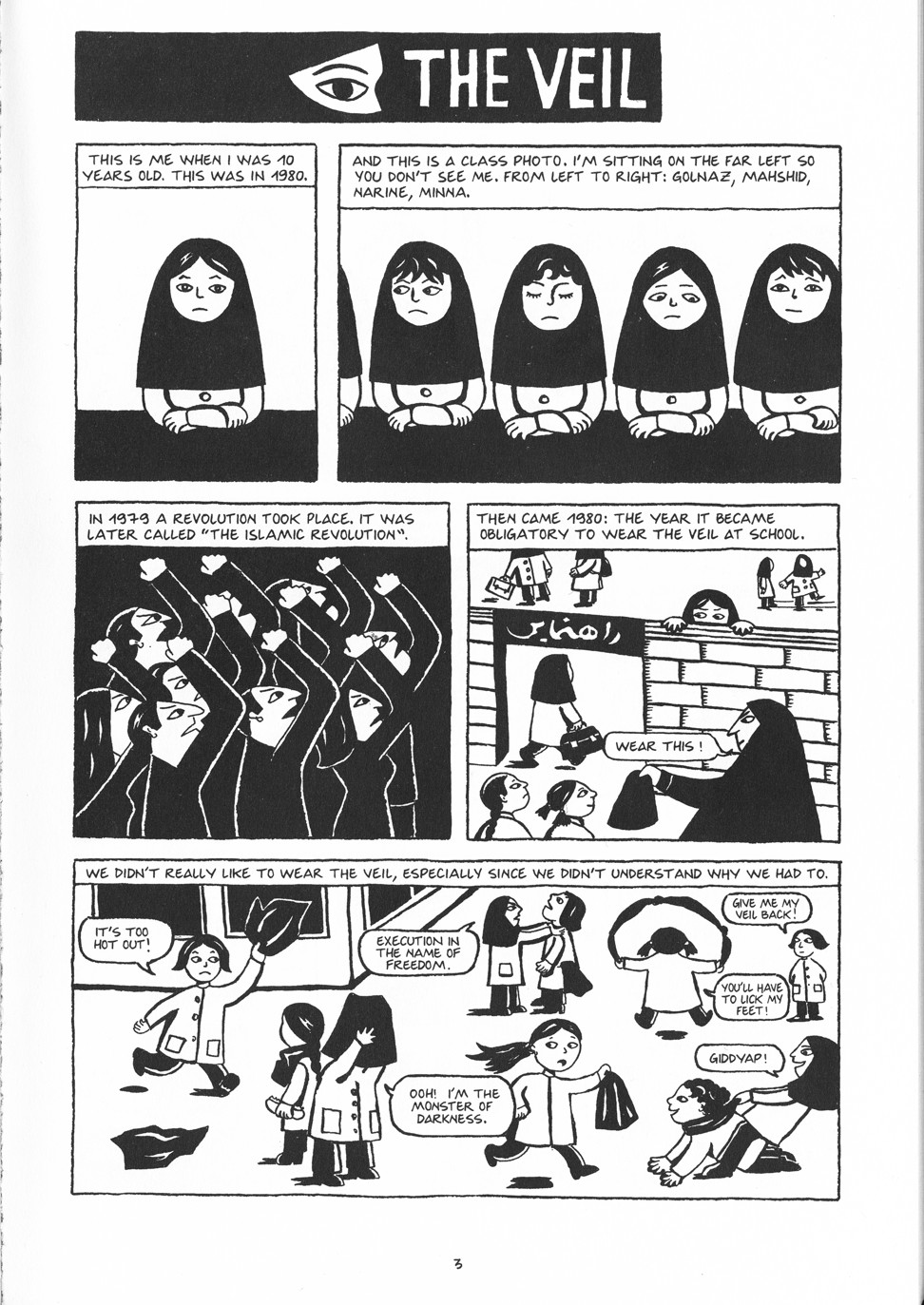

The broader sweeps of history have been recorded in graphic memoirs. There is an unparalleled immersive immediacy to the hand-drawn, handwritten, black-and-white, personal stories of the Holocaust and Iran’s Islamic regime in Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1980-91) and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000).

These accessible and acclaimed autobiographical works – Maus won a Pulitzer prize; Persepolis was taught to soldiers at the US’ West Point Academy – are essential foundation stones of the modern medium and continue to inspire other works of graphic non-fiction.

The Spectators – a graphic novel about life in Paris

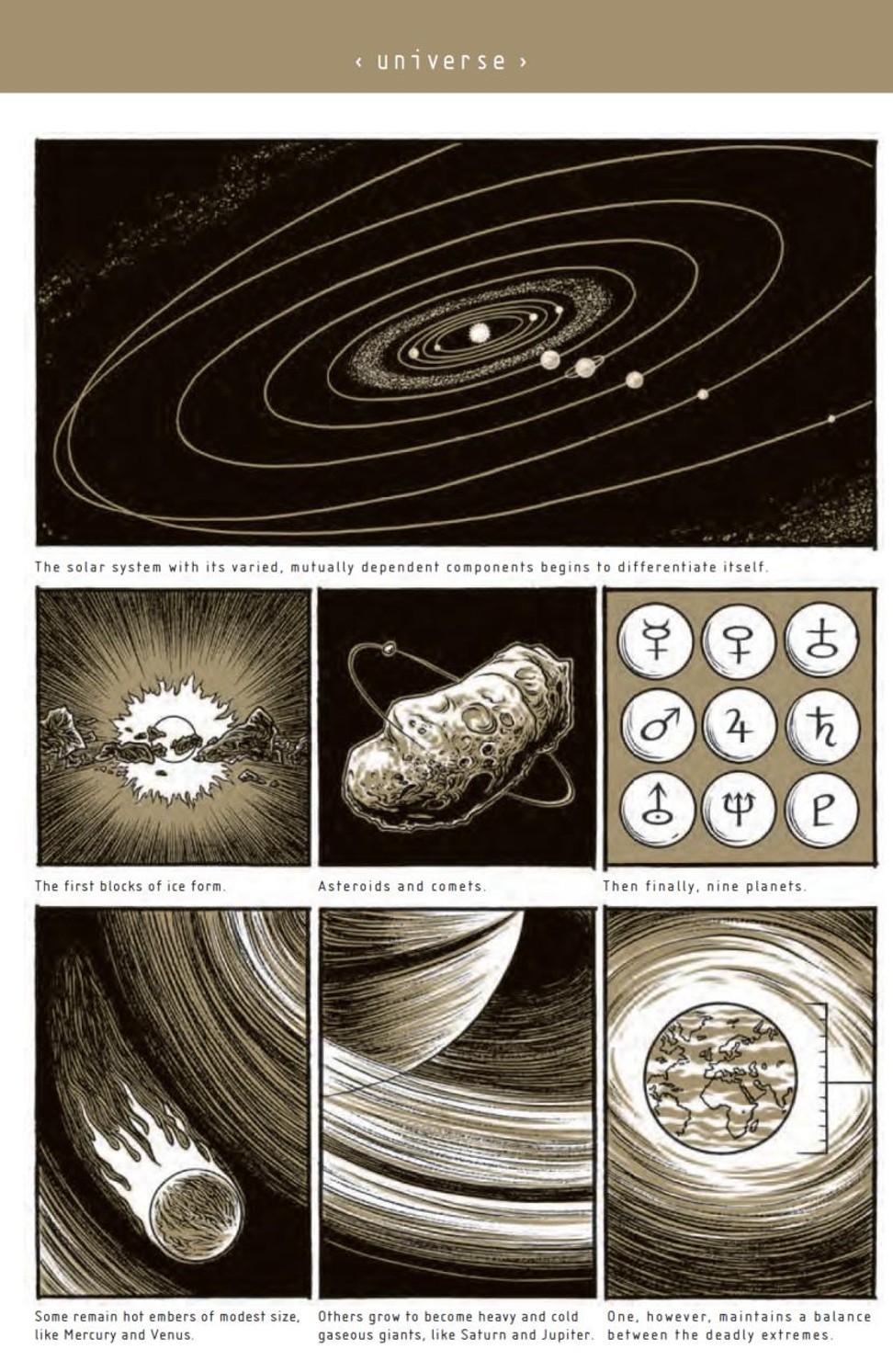

Nothing less than the entire birth and evolution of our world and species are explained in the massive Alpha by Jens Harder (2009). His scintillating, mosaic-like spreads are crafted out of a multiplicity of images, from ancient to modern, interspersed with supplementary notes.

Harder’s follow-up, Beta, not yet in English, and the forthcoming Gamma will complete his madly ambitious project.

Rich writing is just as important as the visuals, and in Tamara Drewe (2005-2007), Posy Simmonds cleverly updates and subverts Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd to observe the stark contrast between a country retreat for comfortable, middle-class writers lusting after the alluring Tamara, and the local working-class teenagers bored stiff in their “event-proofed” village.

Another of Britain’s great world-builders is Chris Reynolds. In The New World (2018), his writing and drawings stretch and twist tenses and times to conjure up a nostalgic near-future, one that is part Edward Hopper, part Andrei Tarkovsky, transposed to post-industrial Wales. Step inside – you’ll find comics have rarely been so hypnotic and tantalising.