Review | Haruki Murakami turns his surreal gaze towards middle age in a tale of art, dislocation, and secrets

Killing Commendatore humourously balances the mundane and the bizarre in a book pulled from the 2018 Hong Kong Book Fair after being classified as ‘indecent’

Killing Commendatore

by Haruki Murakami

Knopf

4/5 stars

The middle of life is a second adolescence, with no one left to admire our suffering. All of Dante’s work is a beautiful, unconvincing riposte to the sense of anguish this age can bring: “Midway along the journey of our life, I woke to find myself in a dark wood, for I had wandered from the straight path,” he writes. Eventually he makes it to Paradise; but nobody reads that part.

The great Japanese author Haruki Murakami grew famous writing about the tender melancholy of youth. (Norwegian Wood made him so recognisable in Japan that he left.) Reading books from that period, you feel sad without knowing why – and yet, within that sadness glows a small ember of happiness, because to feel sad is at least to feel honestly.

Thanks, but no thanks. Japan’s Murakami snubs ‘alternative’ Nobel

Now, in his 60s, he has begun to consider middle age more carefully, as if he sees himself most clearly across a 20-year lag. It’s the subject of his underrated Colourless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, and also of his immersive, repetitive, big-hearted novel Killing Commendatore, just released in English translation after its initial publication in Japanese in 2017.

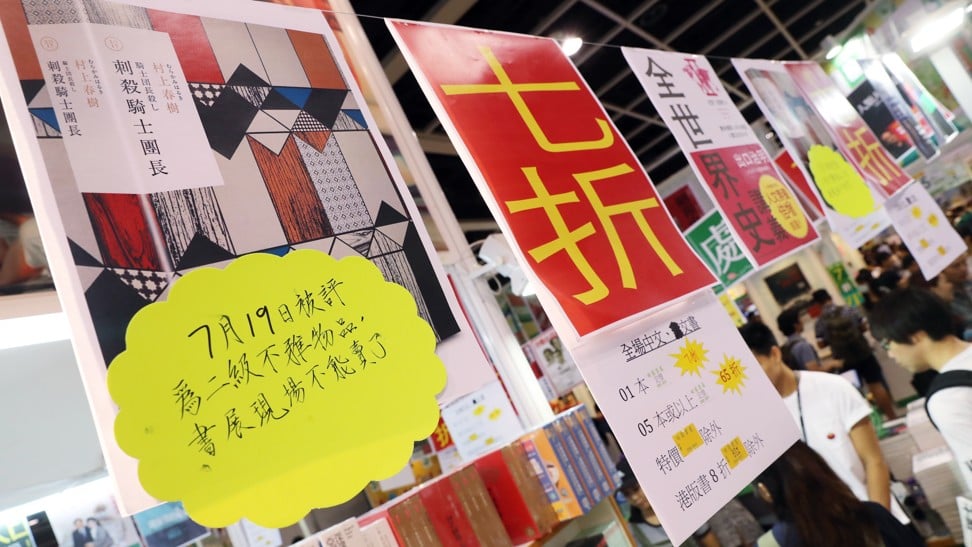

A Chinese translation of the novel was classified as “indecent” in Hong Kong in July – it was then pulled from the Hong Kong Book Fair and banned for those under 18 in public libraries.

The narrator of Killing Commendatore is a painter of 36. His wife has just left him. Having sacrificed his early ambitions as an artist to become a master portraitist, he leaves his Tokyo flat bewildered, before coming to a realisation: “I … wanted to try painting whatever I wanted.” A friend from art school lends him a remote house in the mountains, and he begins to search anew for the meaning he once found in pure creation.

As is often the case in Murakami’s fiction, a plot of relative simplicity – an artist’s reinvention – is disrupted by enigmatic, surreal or violent incidents. The narrator’s new residence once belonged to a famous painter, whose peculiar depiction of a sword fight, Killing Commendatore, remains in the attic. Soon after finding the painting, the house’s new inhabitant begins to hear the clear sound of a bell emanating from a “strange circular pit in the woods”. These events disturb him, while also pressing him into a furious creativity; he begins to paint abstract portraits, not simply of faces and bodies but of the souls within them.

One of these portraits is of a mysterious, immensely rich man named Menshiki, who lives nearby. He has bright white hair, a Jaguar and a “very clean, open smile,” while concealing, the painter thinks, “a secret locked away in a small box and buried deep down in the ground.”

It is Menshiki who manages the excavation of the pit. Inside, they find only the ancient bell – but its call brings to life (hold steady here, if you can) a two-foot-tall character from the ominous painting, with a message of mortal importance.

This stuff is very Murakami. Killing Commendatore repeats almost exactly, for example, the descent through a well to a magical world that occurs in his earlier novel The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Odd creatures constantly come to life in his writing, perhaps most memorably the human-size frog calmly preparing tea in the short story “Super-Frog Saves Tokyo”.

Yet there’s a strong sense in Murakami’s work that his allegorical instincts are secondary, the radiation of his characters’ inner sense of dislocation. He took this method to its outermost limits in his monumental 1Q84 (is it time to admit that that book is something of a mess?), but Killing Commendatore gets the balance right. Murakami’s characters want to turn themselves inside out, to escape the indecipherable mechanical momentum of their lives. The only path he offers them out of that despair is art; the narrator of Killing Commendatore learns “the courage not to fear a change in one’s lifestyle, the importance of having time on your side.”

A Japanese author’s fight against whitewashing the horrors of history

They are humble lessons, given the ridiculous events that have befallen him. But that’s the point. Nothing we invent could be as strange as life. We honour that fact by inventing it anyway.