The perfect book to celebrate Chinese New Year is a 250-year-old tome full of ghosts, demons, monsters, monks and more

- Fast paced, surprisingly light in tone, emotionally cool, and wryly humorous, Pu Songling’s Strange Tales From a Chinese Studio runs to 500 tales

- Love is a recurrent theme, often between a studious young man and an enigmatic beauty who turns out to be a were-vixen

Sometimes the mood is one of enchantment and melancholy, of moonlit evenings when soft rain mists the windows and memories lie heavy on the heart. More often, though, Pu Songling’s Strange Tales From a Chinese Studio calls to mind a collection of mildly racy club stories or lost episodes of The Twilight Zone.

Reading this beloved classic provides a particularly enjoyable way to help celebrate Chinese New Year. The festivities for the Year of the Pig officially start on February 5 but have already launched and will continue until February 19. Strange Tales From a Chinese Studio will last readers the entire two weeks and more. While several English versions exist, John Minford’s Penguin selection of 104 stories is arguably the best, in part because of its scholarly introduction and abundant endnotes, most of which incorporate some of Pu Songling’s own commentary on his work.

Burmese folk tales: stories of a people with one foot in the past

Born in 1640, Pu Songling worked at various clerical jobs in the northern province of Shandong. He died in 1715, leaving behind almost 500 accounts of the wondrous, eerie and grotesque, some derived from oral narratives. Finally printed in 1766, Strange Tales From a Chinese Studio overflows with ghosts, demons, monsters, monks, magicians, revived corpses, gods and fox-spirits, these last being vampiric creatures that assume the outward form of attractive men or women.

Love is a recurrent theme, often between a studious young man and an enigmatic beauty of unknown background who, alas, generally turns out to be a revenant or were-vixen. Invariably, the couple make love – Pu treats sex quite matter-of-factly – and the human protagonist soon thereafter wastes away and dies, though not always.

Fast paced, surprisingly light in tone, emotionally cool, wryly humorous – these uncanny tales, often just one or two pages long, might almost be adult bedtime stories. Sometimes Pu claims to have heard them from a relative or passer-by, thus adding an introductory fillip of verisimilitude, but at other times he plunges directly into the action with an abruptness and simplicity reminiscent of Chekhov. Consider the following three opening sentences:

“A youth by the name of Zhao, from Yishui, was on his way home from a commission in town when he caught sight of a girl in white standing by the side of the road, weeping and seemingly in great distress.” (“The Girl From Nanking”)

“A man named Zhang died suddenly and was escorted at once by devil attendants into the presence of Yama, King of the Underworld. Yama checked his registers and turned angrily to the attendants, informing them that they had brought the wrong man and were to take him back immediately.” (“A Most Exemplary Monk”)

“A certain Mr Liu, a second-degree graduate of the same year as my father’s cousin Pu Wengui, had the ability to remember his various past lives, and was able to relate them in some detail.” (“Past Lives”)

Given such sentences, you would need a will of iron to stop reading. Why is the girl crying? What will happen to Zhang in the Underworld? What were Mr. Liu’s past lives?

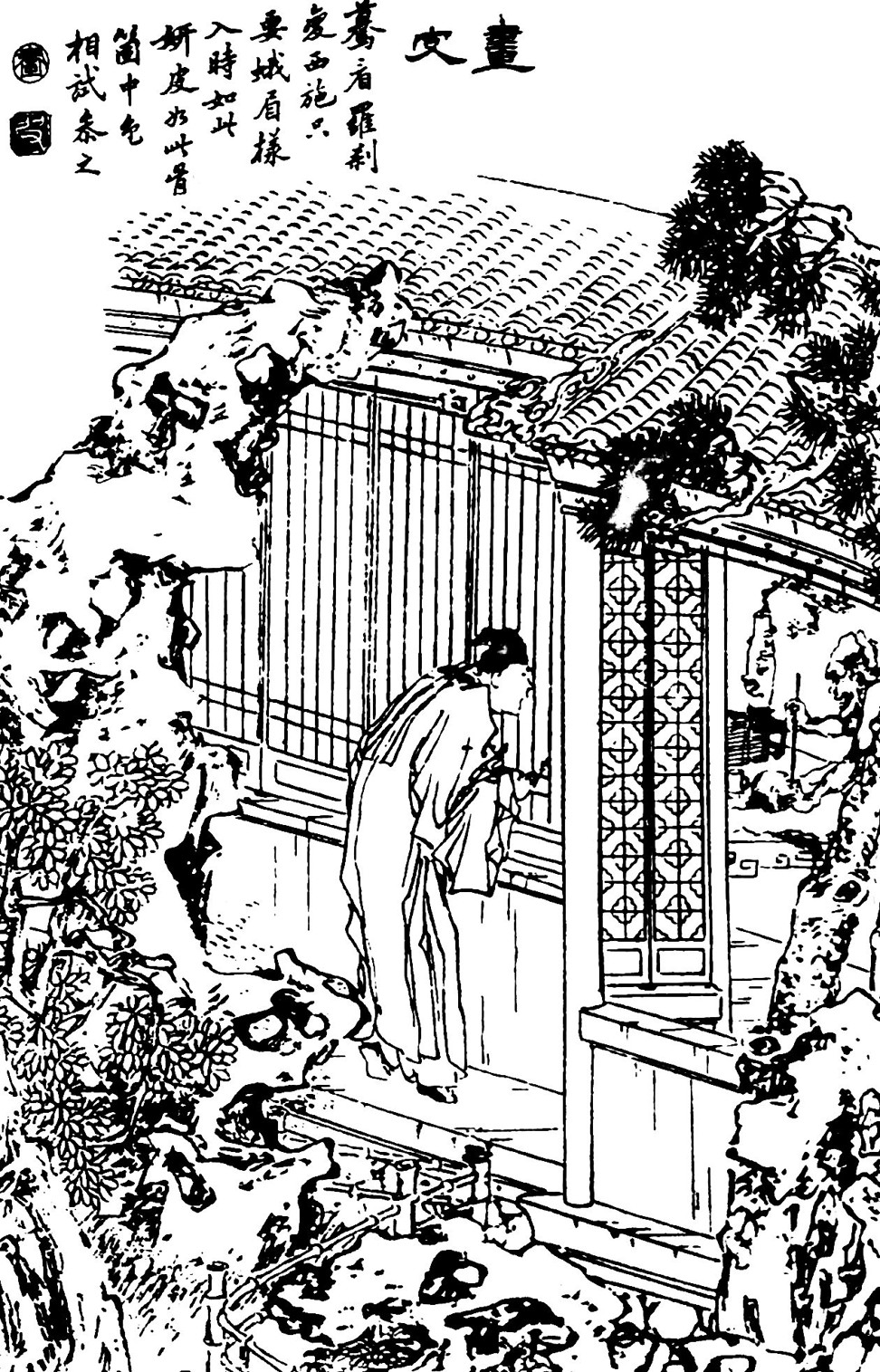

In “The Painted Wall” the Provincial Graduate Zhu visits a Zen monastery where he lingers before a mural, mesmerised by the image of a smiling maiden with unbound hair. The next moment Zhu has been transported bodily into the painting itself – and his adventures have just begun. In “Talking Pupils” a notorious libertine is blinded for making unwanted advances, only to discover that tiny beings live inside his eyes.

When the protagonist of “The Painted Skin” initiates a passionate affair with a young woman of ethereal beauty, she makes him promise never to mention her existence to anyone. One night he secretly peeps through a window and sees “the most hideous sight, a green-faced monster, a ghoul with great jagged teeth like a saw, leaning over a human pelt, the skin of an entire human body, spread on the bed … The monster had a paintbrush in its hand and was in the process of touching up the skin in lifelike colour.”

Pu’s stories generally deliver short sharp shocks, but the longer ones delineate the often subtle dynamics of intimate relationships. The tender “Grace and Pine,” recounts the mutually rewarding platonic friendship between a young scholar and an otherworldly family of fox-spirits. In “Twenty Years a Dream” the protagonist’s devotion to a ghost is so great that he eventually brings the dead woman back to life.

One of Pu’s masterpieces, “Lotus Fragrance” begins as French farce when Sang Xiao finds himself alternately the lover of both a ghost and a fox-spirit, each insanely jealous of the other. But following a near-death experience and two instances of reincarnation, the trio ultimately settles into a harmonious ménage a trois.

Overall, this self-described “Chronicler of the Strange” sympathises with every manifestation of Eros the bittersweet. A lonely woman turns to a pet dog for comfort, a child-bride finds herself unknowingly pregnant, a merchant’s wife grows hypersexualised after being assaulted by a fox-spirit.

How Aladdin’s original Chinese identity was lost in Hollywood

In “Cut Sleeve” an academician longs for a pretty young man – in fact, another fox-spirit – who agrees to exchange his favours for a special medicine needed by his sick grandmother. This is only the beginning, however. In his next life the academician weds his former lover’s gorgeous female cousin, while the fox-spirit nobly prostitutes himself to the province’s governor to protect the happy couple. The whole story concludes with a satirical poem that uses double-entendres to poke fun at the puritanically intolerant.

In an endnote, Minford aptly characterises these stories as “subtle, contained, cultivated, not showy; poised, poignant, leaving much unsaid for the reader to think about.” All true, but, above all, they are magical and wondrously entertaining. Happy new year!