What North Korea is actually like: view of a US author in Pyongyang

- Travis Jeppesen’s travel memoir is one of the better – albeit personal and anecdotal – introductions to the North Korea of today

- He portrays North Koreans neither as brainwashed drones nor as helpless, abject figures whose humanity comes to light only via neo-colonial sympathy

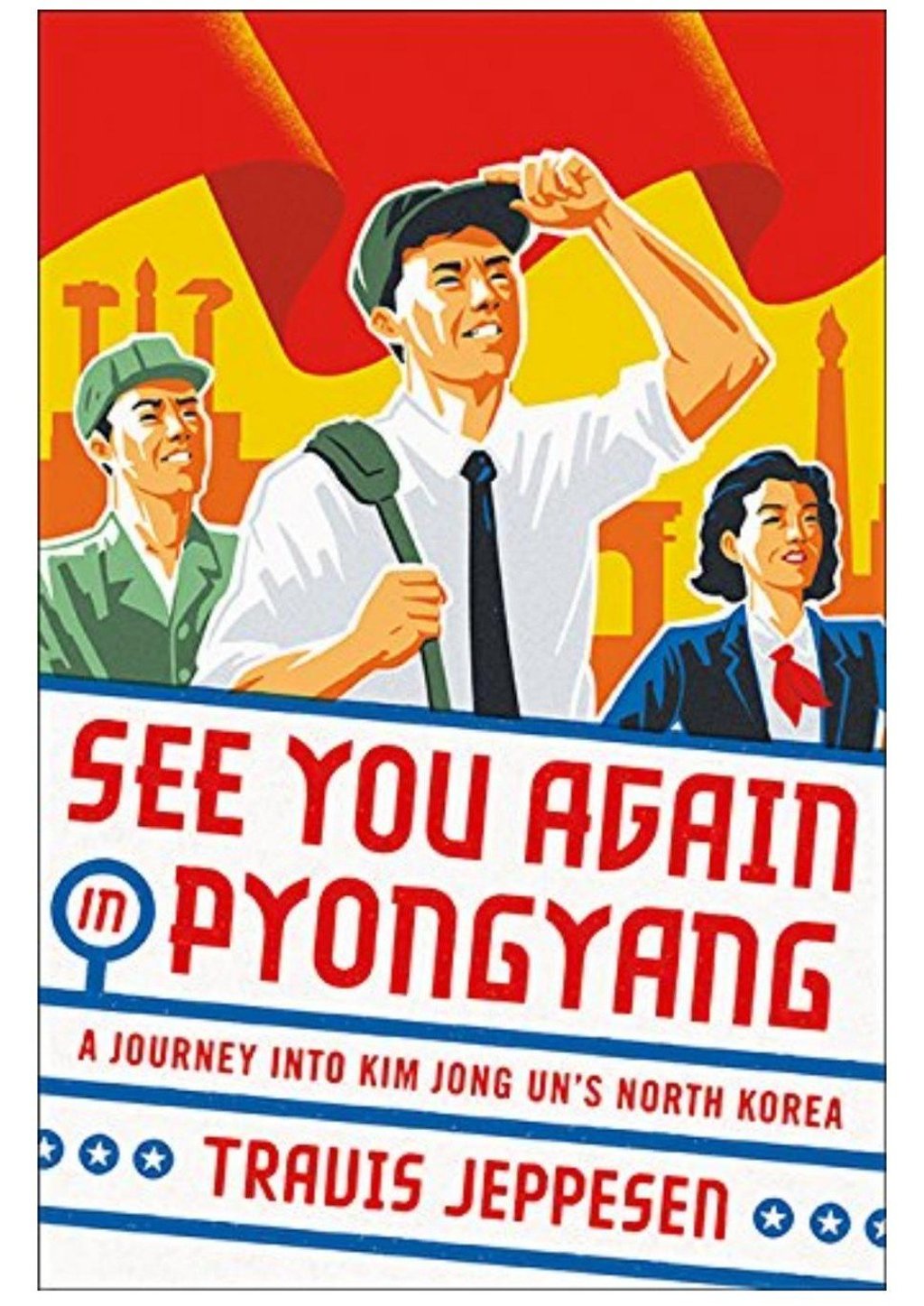

See You Again in Pyongyang: A Journey into Kim Jong Un’s North Korea by Travis Jeppesen. Published by Hachette. 4 stars

When Travis Jeppesen, a 37-year-old writer and art critic, spotted the ad offering a one-month study programme in North Korea, he didn’t hesitate. Not that he was any wide-eyed naif: he had visited four times before.

But he was done with package tours, with being shuttled from monument to tedious monument. If he were to return to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), it would have to be for a different sort of trip.

Enter Tongil Tours. Newly founded by Alek Sigley, a geeky, North Korea-obsessed Australian, in 2016, Tongil was looking to carve its own niche in the North Korea travel market – specifically with educational programmes.

Sigley’s marquee project was what Jeppesen would stumble across: a one-month trip learning Korean at Kim Hyong Jik University of Education in the North Korean capital, Pyongyang.

See You Again in Pyongyang is the outcome of Jeppesen’s trip. Spending mornings learning basic Korean from the flirtatious Ms Pak and afternoons trying to understand this riddle of a country, Jeppesen descends below the political patina coating North Korea.