Chaplin’s World, museum about Charlie Chaplin’s life and work, opens in Switzerland

15 years in the making, the Swiss Riviera-set showcase gives visitors insights into the comic actor’s humble beginnings in London and his spectacular rise to the status of Hollywood movie legend

Imagine moving along the cogs within giant machinery like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times, or tumbling inside a cabin teetering on the edge of a cliff as he did in Gold Rush.

That will be possible when an ambitious, immersive museum showcasing the life and works of the groundbreaking filmmaker opens in Switzerland on Sunday.

Chaplin’s World, 15 years in the planning, will premiere in the picturesque village of Corsier-sur-Vevey on Lake Geneva one day after what would have been the British screen legend’s 127th birthday.

“He wanted people to remember him. That’s why he did the films and he did it in such a perfectionist way,” Chaplin’s 62-year-old son Eugene says. “I think he would be pleased.”

The museum is set on the vast estate of Manoir de Ban, about 26 kilometres (16 miles) from Lausanne, where Chaplin spent the last 25 years of his life until his death in 1977 at age 88.

He had moved to Switzerland after being barred from the United States in the 1950s over suspicions that he had communist sympathies, at the height of paranoia about Soviet infiltration.

On the Swiss Riviera overlooking the lake with a view of the Alps in the distance, the large manor where Chaplin lived with his wife Oona and their eight children forms half of the museum, retracing the filmmaker’s private life.

This is the perfect place to show my father’s films, to remember his work, and his life, in a place where he was so happy

Chaplin’s 70-year-old son Michael recalls what it was like living in the mansion, with about a dozen servants.

“It was like Downton Abbey, on a reduced level. For a child it was wonderful,” he says, recalling all the great hiding places.

A separate building has been built nearby as a large mock-up of a Hollywood studio dedicated to Chaplin’s on-screen work which began about 1914.

Visitors can also catch a glimpse of the artist’s humble beginnings in London and his spectacular rise to become one of the biggest, most influential movie legends in Hollywood history.

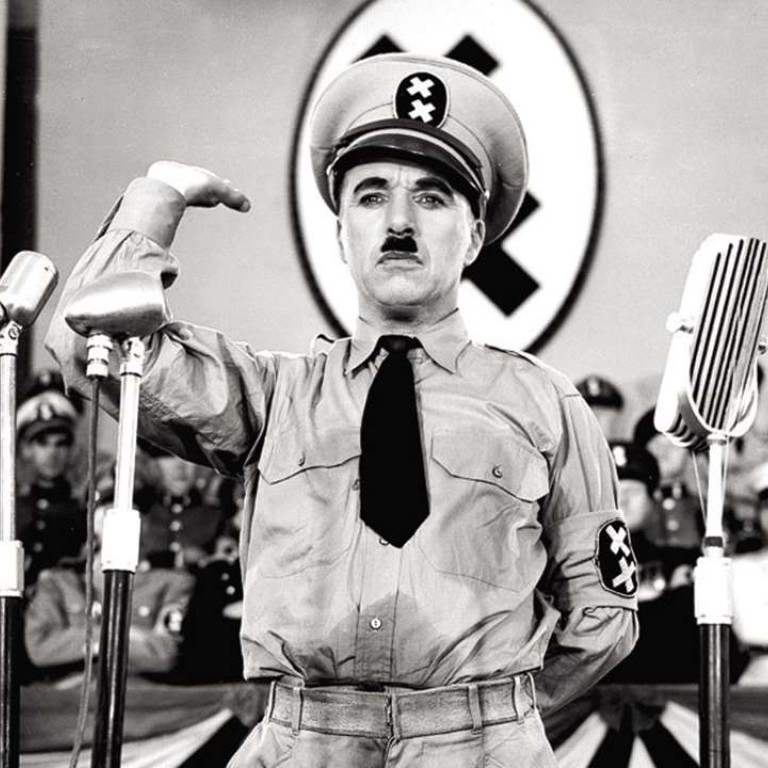

With clips from his iconic films flickering from a multitude of screens, visitors can walk down Easy Street, visit the barber shop from The Great Dictator and the restaurant where he ate his shoe in The Immigrant.

“What really touched me is how they managed to make his films come alive again by inserting clips into decors,” Michael Chaplin says, recalling how his father “was always in movement, and that part of the museum is in total movement, which is beautiful.”

Chaplin’s World is also dotted with more than 30 wax figures created by the Grevin wax museum in Paris.

The lifelike figures portray Chaplin as different characters, his wife Oona, actors and actresses from his films, friends and people who mattered to him such as Albert Einstein, as well as artists inspired by his work such as Michael Jackson and Woody Allen.

“We worked very hard to make a museum that would be as true as possible,” curator Yves Durand says ahead of the opening.

“We are there to tell a story about a real life that was Charlie Chaplin’s life, and about a fictional life that was his work,” he says.

In a narrow room resembling a Swiss bank vault, one can find some of the iconic objects associated with Chaplin’s work, including his bowler hat and cane of his Little Tramp persona, and the ripped trousers and patched shoes he wore in The Kid.

“This is the first time I’ve seen the costume, or the cane or the hat or the shoes,” Michael Chaplin says as he helped unpack the items before the museum opening.

“I’ve never actually really seen an original one before, so it’s quite moving to see that.”

In one glass showcase there is the certificate signed by Britain’s Queen Elizabeth when Chaplin was knighted in 1975.

And in another is the Oscar he won for the score of his film Limelight. However, he didn’t win the Oscar until 1973, since the film was barred for release in the US when it first came out in 1952.

The museum project has faced numerous stumbling blocks over more than 15 years of drawn-out negotiations.

It took seven years to get a building permit, and before that organisers had to wait five years to settle a lawsuit brought by a neighbour worried about the implications of the project.

Eugene Chaplin admits the transformation of Manoir de Ban, where he was born in 1953 and lived until 2008, was difficult and says he had stayed away while the work was being done.

“I didn’t want to see the bulldozers digging into the grass. It’s a lot of memories,” he says.

But he was thrilled with the final result.

“This is the perfect place to show my father’s films, to remember his work, and his life, in a place where he was so happy,” he says.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)