How Romania’s cinematic domination at Cannes is a tale of two rival directors

The films of Cristian Mungiu and Cristi Puiu explore similar themes and have similar aesthetics – but while Puiu may have started the Romanian New Wave, it is Mungiu who has taken it to the greatest glory at Cannes

As the Cannes Film Festival wound down last month, the festival jury offered a reminder of how large a shadow one small country has cast on this gathering.

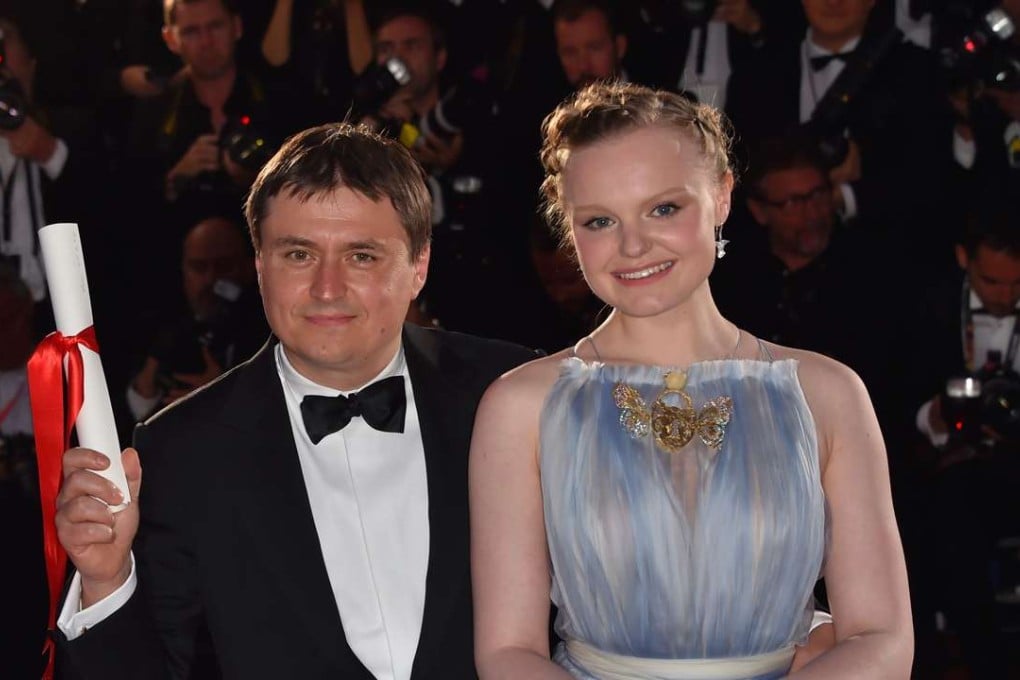

Romanian director Cristian Mungiu took the director’s prize (he shared it with French filmmaker Olivier Assayas) for Graduation, a story/parable about a father who skirts ethical lines in the name of his family. The trophy became the latest prize for a country that, with apologies to Donald Trump, just seems to win, win, win.

It was fully 11 years ago that Cristi Puiu’s The Death of Mr. Lazarescu , about the ways a health care system fails a dying man, took the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes, kicking off the so-called Romanian New Wave. Two years later Mungiu won the Palme d’Or for his period abortion drama 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days .

Ever since, the Romanians have turned out complex, interesting and subtle work, reliably, every year, often using their signature long shots and rigorous minimalism. California Dreamin’, 12:08 East of Bucharest , Beyond the Hills and Police, Adjective have all won major prizes at Cannes in recent years. If you’ve never seen Radu Muntean’s infidelity drama Tuesday, After Christmas , which was at Cannes in 2010, stream it tonight; it will immediately make your life more profound by a factor of three. Other films, such as Child’s Pose, Tales From the Golden Age and Aurora all have their virtues too. This is less a new wave than a persistent surf-pounding.