University of Hong Kong launches MOOC to teach film buffs how Hong Kong cinema conquered the world

Free six-week English-language course delves into the films of movie magicians John Woo, Bruce Lee, Chow Yun-fat, Jackie Chan and Wong Kar-wai and their place in popular culture

Ever wondered about the key elements that make up Hong Kong’s unique blend of movie magic?

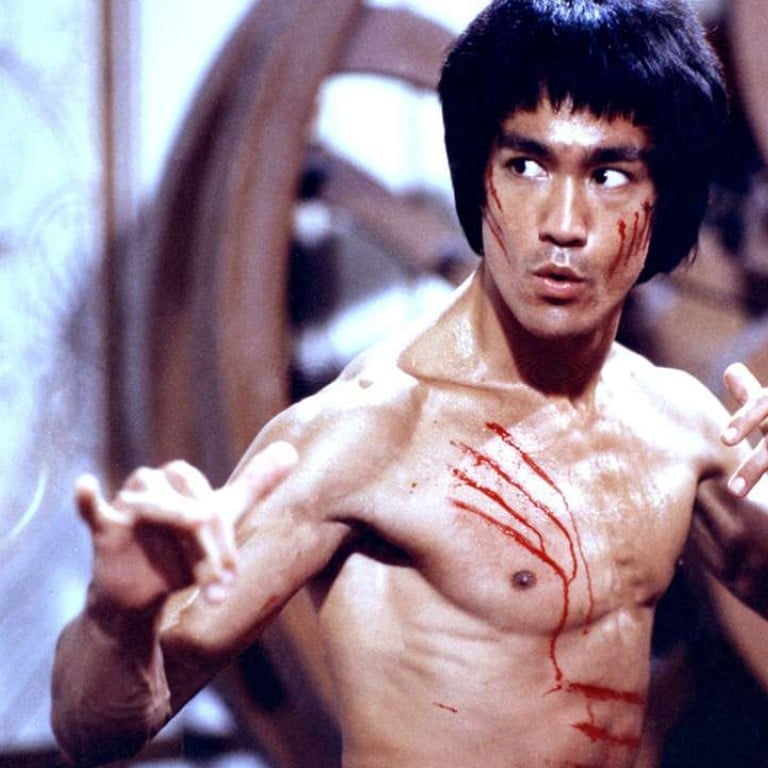

Film buffs around the world can take a free online course that delves into the elaborate choreography of wuxia swordplay, the universal appeal of Chow Yun-fat’s “bromance”, local directors’ handling of gender, race and migration, and of course, two lean, mean fighting machines called Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan.

On February 7, the University of Hong Kong will launch a six-week English-language MOOC (massive open online course) on “Hong Kong cinema through a global lens”.

This is a condensed version of an undergraduate level course that looks at how local cinema has become an integral part of global popular culture (think kung fu), shaped the world’s perception of the Chinese, and offered uniquely Hong Kong perspectives on the immigrant’s experience, gender and other issues.

It will also look into such perplexing issues as why John Woo’s Hollywood films bear so little resemblance to his Hong Kong works and why the world loves Jackie Chan but Hong Kong doesn’t.

Professor Gina Marchetti from the university’s comparative literature department says the course could help address the dearth of study materials on Hong Kong films compared to other major cinematic influences. “You cannot understand the global film industry without understanding Hong Kong films,” she said at a public seminar about the MOOC.

The course is being offered at a time when the decline of Hong Kong cinema seems a forgone conclusion. Cultural critics have blamed a brain drain which has seen the likes of Woo and others move to China and Hollywood, as well as local investors’ tendency to cater to mainstream tastes in China, now the world’s second-biggest film market.

No young Hong Kong star has emerged to challenge the international status of the generation who found fame before the turn of the millennium, and no Hong Kong film has been nominated for best picture in the Asian Film Awards for the third year in a row.

Still, the course isn’t offered as a mere confidence booster for the city’s bruised ego or a nostalgic look back at past glories, its designers say.

“Hong Kong is still a key player within global cinema. To make money now, Hollywood has to connect to China and Hong Kong provides experiences that Hollywood needs,” says Aaron Han Joon Magnan-Park, the comparative literature assistant professor in charge of the action films units.

“Meanwhile, mainland China wants to create a soft power platform but it cannot produce films consistently that have appeal beyond its borders. Again, here is where Hong Kong’s expertise is necessary.

“Most national film industries require a large population base. Hong Kong, by itself, should never have been successful. Hong Kong cinema has always been a player in between the shadows of larger players. Yet, it is successful and provides so much bang for the buck,” he adds.

Referring to his area of specialty, he says Hong Kong action films offer an alternative aesthetic influenced by Chinese culture, intentionally do not replicate what Hollywood does and still hold wider appeal than Chinese productions.

“A successful action film has to have a feistiness to its ethos. Hong Kong’s tradition – from the wuxia martial art films to the modern triad movies – is always about making a break from authority. The principal character becomes the true hero because he is willing to disobey the commands of his master and address a greater injustice. The hero is not willing to become a subservient sheep. For me, that is beautiful,” says Magnan-Park.

That “feistiness” is something that action films from China tend to lack, he adds, since filmmakers are not allowed to “scream out for freedom” or portray the country in a negative light, he says.

Marchetti says the course will be taught through recorded lectures, interviews with directors, a reading and film-watching list, online quizzes and question-and-answer sessions. Enrolment after February 7 is allowed and the course materials will be archived and made available after the course ends in March.

This is not a chance to see Hong Kong films online for free, however, as the lectures will only show limited clips and students are expected to find the films on their own.

The films that you need to watch for the course

Any Jackie Chan film.

Any Bruce Lee film, but especially Fist of Fury / The Chinese Connection (1972), or Enter the Dragon (1973).

An Autumn’s Tale (dir. Mabel Cheung, 1987).

The Killer (dir. John Woo, 1989).

Infernal Affairs (dir. Andrew Lau and Alan Mak, 2002).

In the Mood for Love (dir. Wong Kar-Wai, 2000).