Ten things we learned about Joshua Wong from the Netflix documentary Joshua: Teenager vs. Superpower

Film about to become available worldwide to 100 million-plus subscribers shows Wong became Hong Kong political activist after realising limits of prayer, didn’t buy Benny Tai’s rules for Occupy, and feared going to prison

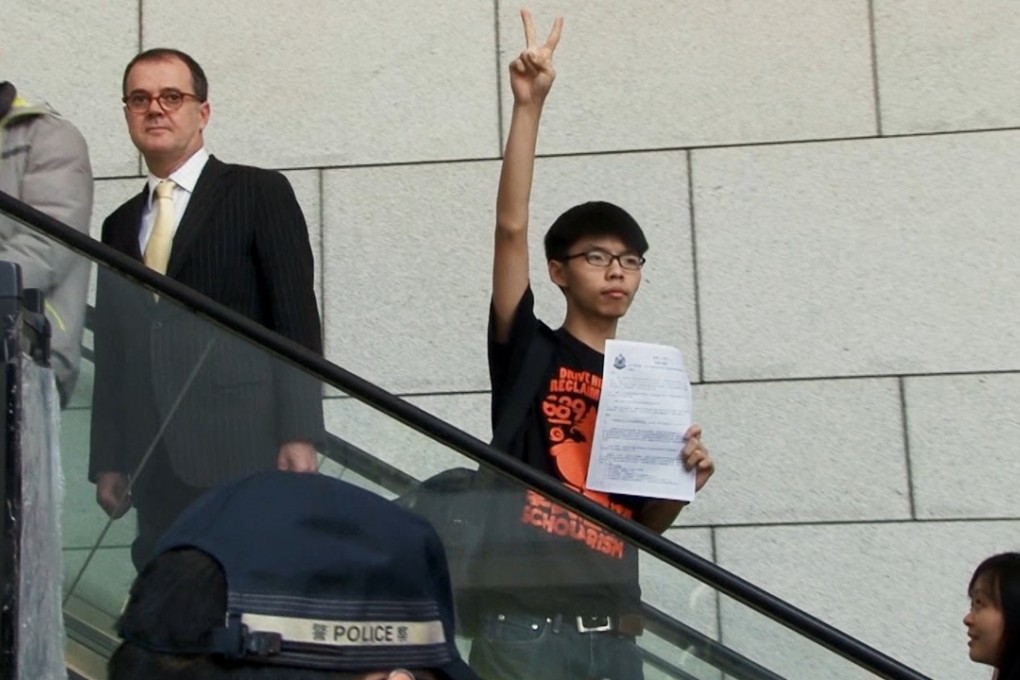

The story of Hong Kong student activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung is set to reach a far wider audience than China would have preferred this week when a documentary about him, Joshua: Teenager vs. Superpower, becomes available for streaming to the 100 million-plus Netflix subscribers around the world on Friday. The film previously won the audience award in the World Cinema Documentary category at the Sundance Film Festival in January.

Packaged as an introduction to contemporary Hong Kong politics, the film contains little that a keen-eyed Hong Kong resident wouldn’t already have glimpsed from the news in the past few years. Here are 10 lesser-known facts about Wong that the Netflix film nevertheless brings into focus.