Best of Cannes 2017: Coppola, Haneke, Netflix row, Palme d’Or winner The Square, and Lynch and Campion’s auteur TV

Sweden’s The Square, an overlong dissection of art world pretensions, took the festival’s top prize, Coppola was a worthy best director winner, and Nicole Kidman was everywhere

This year’s Cannes Film Festival was a cocktail of celebration, controversy and chaos – so business as usual, you might say.

The celebratory feel came courtesy of the fact it was the 70th edition.

As for the chaos, that came with increased security. With airport-style metal detectors and thorough bag searches employed, screenings were delayed, not least that of Michel Hazanavicius’ infectious Jean-Luc Godard-centred film Redoubtable. But after the horrors the French people have faced over the past 18 months, and the suicide bombing that claimed the lives of 22 people in Manchester mid-festival, most were accepting of the tightened measures.

The controversy began even before the festival itself, with two films in official competition, South Korean Bong Joon-ho’s charming monster movie Okja and Noah Baumbach’s family saga The Meyerowitz Stories, owned by Netflix. France’s National Federation of Cinema Owners complained bitterly about their inclusion, given the increasingly powerful streaming service has no intention of exhibiting the films in cinemas.

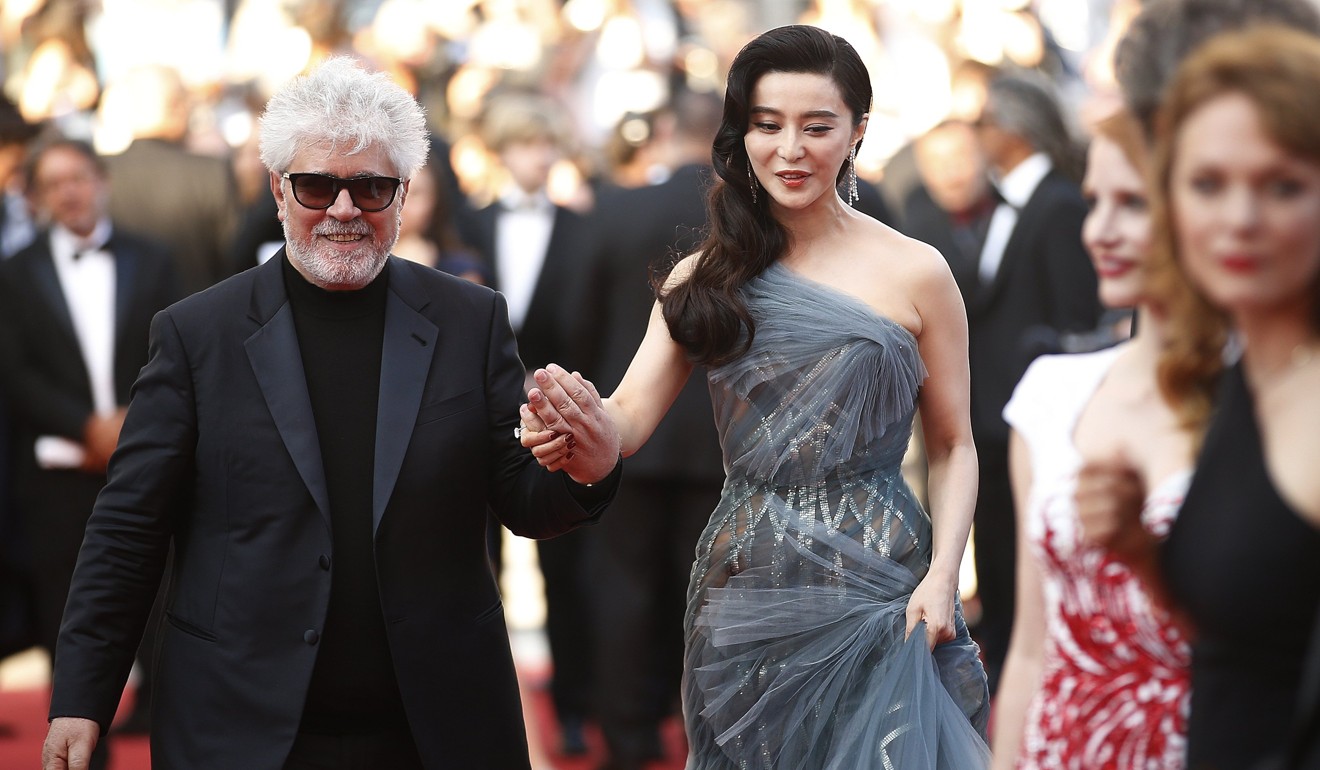

Cannes was forced to change its rules for next year’s selection. But it didn’t stop there. Pedro Almodovar, head of the jury, weighed in, saying: “I personally don’t perceive the Palme d’Or [should be] given to a film that is then not seen on the big screen.”

The future of cinema – where and how we will watch films in years to come – became the festival’s hot-button topic. With Netflix casting its shadow over everything, it was as if British filmmaker Peter Greenaway’s oft-trumpeted dictum that cinema is dead was not so far-fetched after all.

Certainly, this was the year that Cannes recognised just what a force television has become. Two new shows directed by past Palme d’Or winners were included: David Lynch’s sublime return to Twin Peaks, which screened four days after it was launched across the globe, and the gripping second season of Jane Campion’s crime-procedural saga Top of the Lake, starring Elisabeth Moss. Both were among the strongest things I saw.

Also impressive was Carne y Arena, a six-and-a-half-minute virtual reality experience created by the Oscar-winning director of The Revenant , Alejandro G. Inarritu. This installation drops participants into a terrifying scenario as a traveller crossing the US/Mexico border, facing patrol cops, dogs, guns and helicopters. Immersing you into a 360-degree scenario that feels utterly real, this felt far more like the future of cinema than simply streaming movies to your TV.

It was also hugely on point, with the refugee crisis a big topic amongst filmmakers. The highest-profile film to deal with the subject was Michael Haneke’s Happy End. The Austrian filmmaker was returning to the competition after winning two Palme d’Or prizes with consecutive films. A portrait of three generations of a bourgeois family living in Calais, Haneke’s latest felt a little undercooked, but a scene where Isabelle Huppert is confronted by a handful of these displaced souls was marvellous.

Another film to deal with the refugee crisis in Calais was Sea Sorrow, a highly personal documentary by activist-actress Vanessa Redgrave that played out of competition. Her first time behind the camera, this frank look at the camps where thousands have gathered in the hope of finding a better life was a painful but provocative watch. Allowing Ralph Fiennes to perform passages from The Tempest was rather unnecessary, but Redgrave’s film does much to highlight the issue.

As for the official competition, it was a good, if not great, selection – and no one film truly galvanised the critics. Swedish director Ruben Östlund’s The Square claimed the Palme d’Or, and should probably be awarded a prize for the film that caused the most debate and division on the Croisette. A savage dissection of contemporary mores set in the art world, it offers a series of great individual moments that never quite hang together, especially over its bloated 142-minute running time.

Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled proved a lush reworking of Thomas Cullinan’s American civil war novel, previously filmed in 1971 by Don Siegel. This story of Colin Farrell’s wounded Union soldier, stirring up hormones as he takes shelter at an all-girls’ school run by Nicole Kidman’s headmistress, won Coppola the best director prize – and quite rightly. It was the most beautiful-looking and artistically controlled film in competition.

The acting prizes were also well chosen by the jury. Diane Kruger, who took best actress, gave one of the performances of her career in Fatih Akin’s Turkish-German film In the Fade, the story of a mother who seeks justice after her husband and son are killed in a bomb explosion. The first German-speaking role of her career (despite hailing from the country, Kruger made her name in France and America), it was a white-knuckle turn.

Taking best actor was Joaquin Phoenix, as a brooding war veteran whose attempts to rescue a young girl from a sex trafficking ring bring disastrous consequences in Scottish filmmaker Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here. It’s the sort of psychologically damaged character Phoenix excels at, though it’s brilliantly modulated by Ramsay, who took a share of the best screenplay prize for adapting Jonathan Ames’ novella into this hallucinogenic study of pain and guilt.

Sharing the prize with Ramsay was Yorgos Lanthimos and his co-writer Efthimis Filippou for The Killing of a Sacred Deer – the second Farrell/Kidman collaboration at the festival and a revenge story spray-painted with jet-black humour.

Kidman also deservedly collected a special 70th anniversary prize for her multiple performances at the festival – which included a punk queen in How to Talk to Girls at Parties, playing out of competition, and a lesbian feminist mother in Top of the Lake.

The lack of a Chinese presence in the official selection was a disappointment, however. While actress Fan Bingbing was on jury duty, just one Chinese film made it into the festival: Li Ruijun’s bleak tale of factory workers, Walking Past the Future. After 2016, when there were no Chinese-language movies, it’s a worrying trend; Cannes selectors are currently more entranced by South Korea, as seen in the inclusion of Okja and Jung Byung-gil’s thriller The Villainess.

Genre films proved popular, with Japanese veteran Takeshi Miike’s Blade of the Immortal getting a lot of love. But I left the festival with a soft spot for Josh and Benny Safdie’s crime movie Good Time, starring Robert Pattinson in a nightmarish 24-hour odyssey that blends bank robberies, ghost trains, LSD and all sorts of weirdness. It was like being transported back to grimy 1970s New York cinema – a world before streaming and VR – and it felt so good.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook

(1).JPG?itok=0BHk6odg&v=1665981271)