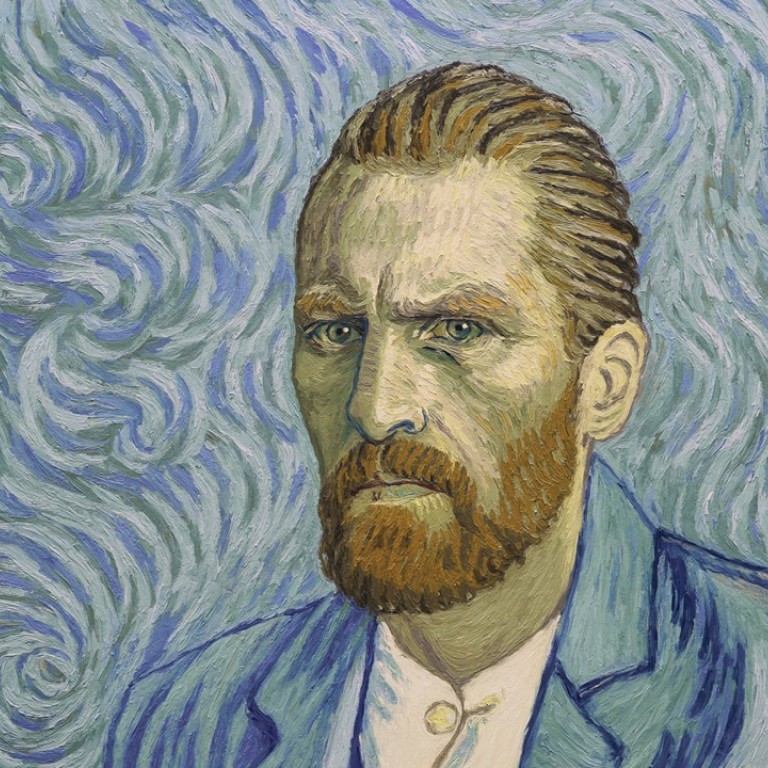

Loving Vincent: how Van Gogh’s life was subject of the world’s first animated film made of oil paint

To make this homage to the great, tragic artist, his works were painstakingly recreated with oil paints and repainted over and over to produce the illusion of movement. In total, 125 artists painted 65,000 frames

It started as a pipe dream, a short film idea about animating with paint. Six years later, Loving Vincent arrives in cinemas as a miraculous achievement.

The “world’s first fully-painted feature film”, as the press materials proudly boast, this full-length homage to the life and work of Dutch post-Impressionist artist Vincent van Gogh is an immersive experience like no other. From Café Terrace at Night to Wheatfield with Crows to The Starry Night, Van Gogh’s masterworks spring to life in mesmerising, hypnotic fashion.

Moreover, rather than using computer graphics, artists painstakingly used oil paints. A full-on image would be painted on a canvas; then elements – say, a person’s head and shoulders – would be scraped off and repainted frame by frame to simulate movement, 12 times for every second of film.

As amazing as that notion is, far more labour-intensive than even animation with clay, Loving Vincent is more than just a gallery of pictures shimmering to life on screen. It’s also a look at the final days of Van Gogh’s life from those who knew him best.

“Vincent had this very dramatic, very personal, very tragic and very heroic story,” says British-born Hugh Welchman, who co-wrote and co-directed the film with his Polish animator wife Dorota Kobiela.

It was trained painter Kobiela who decided a decade ago, after re-reading a book of Van Gogh’s letters, that she wanted to turn her love for this artist into a unique portrait. But it only blossomed into a fully-fledged idea when she met and married Welchman, after working for his production company BreakThru Films, the outfit behind the Oscar-winning 2006 short Peter & The Wolf.

Nicholas Hoult on making J.D. Salinger biopic Rebel in the Rye, playing Tesla in The Current War, and erotic romance Newness

Initially, Welchman was going to produce and Kobiela direct, from a script penned by a hired writer. “What I knew about Vincent was what most people know about him,” says Welchman. “He cut off his ear, he went mad, he did these swirly amazing paintings and they sold for lots of money.”

But after reading “every major publication since 1920” on the artist, it became obvious that Welchman and his wife should write the script and co-direct.

“When you read about Vincent,” he says, “he obviously had a problem relating to people, and yet if you read his letters, he was a superb communicator and very eloquent, and his paintings now communicate to millions of people. So we really wanted to get away from how you portray Vincent’s particular craziness and more concentrate on being in a world full of his words and paintings.”

Seven drafts later, the result was indeed far removed from straight-up biopics such as Robert Altman’s Vincent and Theo or the Kirk Douglas classic Lust For Life.

Set a year after Van Gogh’s death in 1890, Loving Vincent explores the theory first aired in the 2011 biography penned by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith: that the artist did not shoot himself in the stomach, but died at the hands of another, 16 year-old bully René Secrétan. In the film, Van Gogh (Robert Gulaczyk) is largely glimpsed in black-and-white flashbacks as others recollect him.

With Empty Hands role, Hong Kong pop singer Stephy Tang is poised to make the leap to serious actress

The main protagonist is Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth) – who, along with his parents and two siblings, was immortalised by Van Gogh in a series of portraits. Encouraged by his postmaster father (Chris O’Dowd), Armand reluctantly begins to question others as to the circumstances surrounding Van Gogh’s death.

“We only ever fictionalised the gaps,” says Welchman. “We didn’t put anything in the film which is against historical fact. That was one of our restrictions which was annoying when we were writing the script.”

In the case of Roulin, little was known about him other than he became a blacksmith in his late teens and later in life a gendarme in Algeria – enough to suggest he would have an aptitude for detective work.

“We also deduced that Armand wouldn’t have liked Vincent when he was in Arles, because this strange foreigner was his dad’s drinking buddy and they’d be out drinking all night,” adds Welchman. “When he cut his ear off, it was probably embarrassing for a teenager to be associated with that kind of person, among your friends.”

Yet as he travels to Auvers-sur-Oise in France, where Van Gogh died, Roulin gradually grows to empathise with the late artist.

If the story offers fresh perspectives on Van Gogh, the real achievement is the animation process. “We didn’t just have to make a film,” says Welchman. “We had to build from scratch a pipeline for large-scale painting animation. It just didn’t exist before this film.”

Why Wind River director Taylor Sheridan – writer of Sicario and Hell or High Water – penned Native American murder mystery

In Gdansk, Poland, auditions were held for artists specialising not in animation, but oil painting. After a teaser for the film went viral, there were 5,000 applicants; 125 artists made the cut.

Early in the process, 60 minutes of live-action footage was shot on rudimentary sets with the cast. That was then used as a guideline. “The artists didn’t just come in and trace everything,” says Booth. “What they had to do was interpret Vincent’s style.”

Welchman and Kobiela spent hours in the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam studying the application of the paint, the drying times and the texture to capture his style.

The dedication to the task was immense. When new research was published last year that Van Gogh cut off his entire ear, rather than just the lobe as previously thought, the Loving Vincent team went and repainted around 3,000 frames of the film.

In total, some 65,000 frames were created on more than 850 canvases; artists worked in three studios in two countries using some 3,000 litres of paint. “Literally blood, sweat and tears have gone into the making of this movie,” says Booth with a smile.

Geostorm star Gerard Butler on the epic disaster film’s ill-timed release, and his own near brushes with historically traumatic events

The choice of Van Gogh’s artworks were “weighted towards the paintings at the end of his life”, says Welchman. Of those selected, 94 were used in the form they were painted in; around 40 others had to be adapted to fit the screen.

With Marguerite Gachet at the Piano, for example, the periphery of the scene had to be expanded both left and right. Seasons, the weather or even the time of day, in certain cases, were altered, adding to the expressionist nature of the project.

Booth, meanwhile, managed to coax British composer Clint Mansell, with whom he’d worked on Darren Aronofsky’s biblical epic Noah, to come on board. Like the title suggests, it was a labour of love for all concerned.

“I would love for Vincent to be around to see what a loving tribute has been made,” says the actor. “The amount of love and affection that people have for him and his work, how connected they are to him [is remarkable – for] a man who only sold one of his paintings in his lifetime.”

Loving Vincent opens on November 9

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook

(1).JPG?itok=0BHk6odg&v=1665981271)