Chinese cinema in 2017: the best may be an overlooked gem with two boys and a punctured football

China’s film industry is changing, with new takes on patriotic propaganda, an animation that Chinese authorities first pulled from a French festival then praised, and a social critique involving a football

China’s turbulent and relentlessly turbocharged film industry has changed much in 2017, something the films shown this year exemplified.

There’s Wolf Warrior 2 , the populist action thriller that devoured all before it during the summer and redefined the way patriotic propaganda films could be made for – and sold to – a new generation of film-goers.

On the flip side is Twenty Two, a documentary about China’s last surviving “comfort women” that is heartbreaking, humanistic and totally devoid of simplistic jingoism.

The Chinese animators pushing back against the Hollywood tide

The comically fatalistic underworld tale of an array of gangsters and slackers in a small Chinese city is now slated for general release on January 12.

Other independent filmmakers have also made a splash with equally edgy fare this year. Wang Bing was first off the blocks with Mrs Fang , a documentary tracking the final days of a bedridden, Alzheimer’s-stricken woman in a Chinese village. The film reflects on how Fang Xiuying’s family and friends react to her slow death: they talk, argue, haggle and weep around what would be her deathbed, their exchanges revealing the gloomy existence of people living on China’s geographical and social margins.

All these films are landmarks in different ways, their pedigrees consolidated and then amplified by box office takings and trophies.

Among these overlooked gems is arguably the most emotionally powerful and socially astute Chinese film of the year, one which offers a harrowing exposé of injustice in contemporary society.

Why, in Chinese cinema, bad things happen only in Binhai

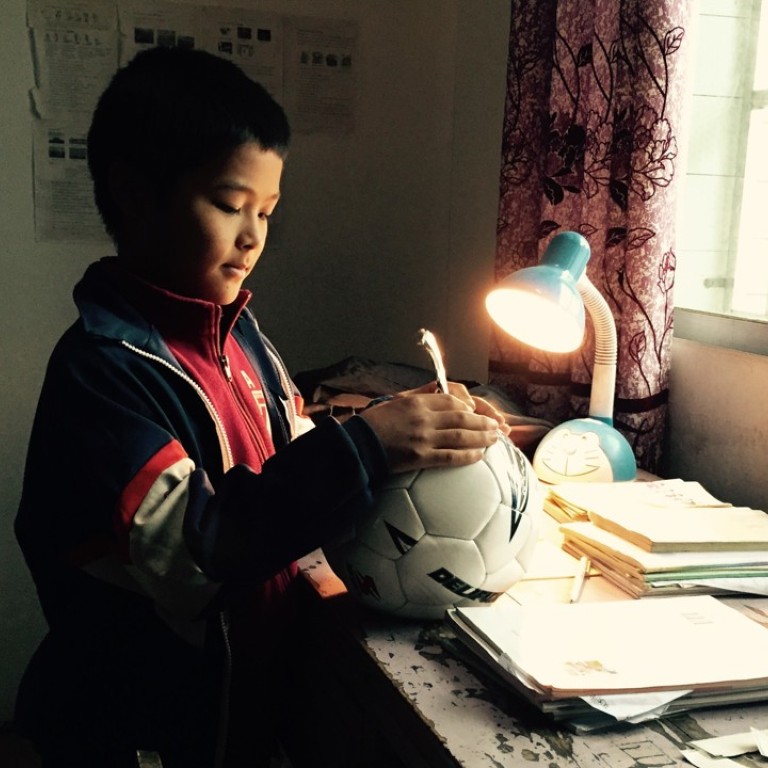

Stonehead – the directorial debut of Shanghai Theatre Academy graduate Zhao Xiang – has what seems to be a very simple premise. A schoolboy from a small village is given a football while receiving an academic prize. When his classmates force him to bring it to school, he punctures it out of spite – a move that backfires badly. Stonehead’s rite of passage as he discovers someone will have to pay the price for his misdeed is heart-wrenching.

Like a character in a film noir, the boy slowly realises how cynicism reigns around him – life can quickly return to normal for everyone as long as someone takes the fall. The teachers are shown to be more concerned with maintaining order and harmony than instructing their young charges in the notions of fairness and empathy. It’s not hard to imagine how all this would play out as these boys grow up.

Coup at Cannes gives art-house cinema in China a boost

Armed with the support of Village Roadshow Pictures’ Asian filmmaking subsidiary – specifically that of its Chinese-speaking chief executive, Ellen Eliasoph, who produced and subtitled the film as well as presenting it to festivals – Stonehead broke out of its indie terrain and premiered at the Berlin Film Festival’s children-oriented Generation Kplus section.

The film has since also been screened as part of the Hong Kong International Film Festival’s Young Cinema Competition.

Describing Stonehead as “minimalist and self-effacing”, Eliasoph says her team is exploring a release of the film in cinemas in the National Arthouse Film Alliance, a state-backed initiative to facilitate screenings of non-mainstream fare at Chinese cineplexes.

It might have missed its chance of becoming one of the best films to hit Chinese screens in 2017, but at least the film will be an early contender for the same race in 2018.